It’s fair to say that few of us now marvel at moving walkways, those standard infrastructural elements of such utilitarian spaces as airport terminals, subway stations, and big-box stores. But there was a time when they astounded even residents of one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world. The innovation of the moving sidewalk demonstrated at the Paris Exposition of 1900 (previously seen here on Open Culture when we featured Lumière Brothers footage of that period) commanded even Thomas Edison’s attention. As Paleofuture’s Matt Novak tells it at Smithsonian magazine, “Thomas Edison sent one of his producers, James Henry White, to the Exposition and Mr. White shot at least 16 movies,” a clip of which footage you can see above.

White “had brought along a new panning-head tripod that gave his films a newfound sense of freedom and flow. Watching the film, you can see children jumping into frame and even a man doffing his cap to the camera, possibly aware that he was being captured by an exciting new technology while a fun novelty of the future chugs along under his feet.”

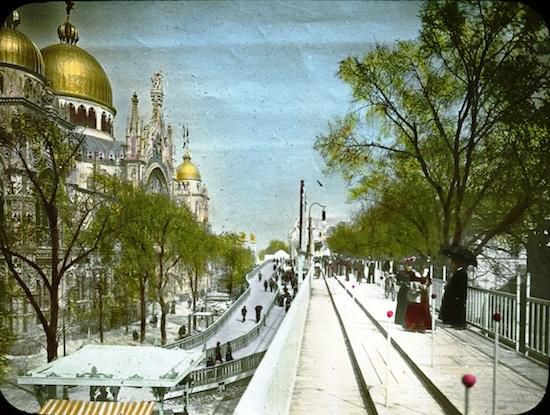

Novak also includes hand-colored photographs from the Paris Exhibition and quotes a New York Observer correspondent describing the moving sidewalk as a “novelty” consisting of “three elevated platforms, the first being stationary, the second moving at a moderate rate of speed, and the third at the rate of about six miles an hour.” Thus “the circuit of the Exposition can be made with rapidity and ease by this contrivance. It also affords a good deal of fun, for most of the visitors are unfamiliar with this mode of transit, and are awkward in its use.”

Novak features contemporary images of the Paris Exhibition’s moving sidewalk at Paleofuture, found in the book Paris Exposition Reproduced From the Official Photographs. Its authors describe the trottoir roulant as “a detached structure like a railway train, arriving at and passing certain points at stated times” without a break. “In engineers’ language, it is an ‘endless floor’ raised thirty feet above the level of the ground, ever and ever gliding along the four sides of the square — a wooden serpent with its tail in its mouth.” But the history of the moving walkway didn’t start in Paris: “In 1871 inventor Alfred Speer patented a system of moving sidewalks that he thought would revolutionize pedestrian travel in New York City,” as Novak notes, and the first one actually built was built for Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition — but it cost a nickel to ride and “was undependable and prone to breaking down,” making Paris’ version the more impressive spectacle.

Still, the Columbian Exposition’s visitors must have got a kick out of gliding down the pier without having to do the walking themselves. You can learn more about this first moving walkway and its successors, the one at the Paris Exhibition included, from the Little Car video above. However much these early models may look like quaint turn-of-the century novelties, some still see in the technology genuine promise for the future of public transit. Moving walkways work well, writes Treehugger’s Lloyd Alter, “when the walking distance and time is just a bit too long.” And they remind us that “transportation should be about more than just getting from A to B; it should be a pleasure as well.” Parisians “kept the Eiffel Tower from the exhibition” — it had been built for the 1889 World’s Fair — but “it is too bad they didn’t keep this, a sort of moving High Line that is both transportation and entertainment.”

Related Content:

How French Artists in 1899 Envisioned Life in the Year 2000: Drawing the Future

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.