Human ingenuity has produced engineering solutions that continue to inspire long after their creators disappeared into history.

Human ingenuity has produced engineering solutions that continue to inspire long after their creators disappeared into history.

Long before modern machinery, builders and inventors relied on raw skill, observation, and clever experimentation to shape cities, move water, tame landscapes, and secure structures against time and nature.

Each innovation reveals a moment when necessity met creativity, leaving behind achievements that still hold up today.

The following photographs offer a visual journey through some of the most fascinating technologies of earlier civilizations and the methods that allowed them to build with surprising precision and durability.

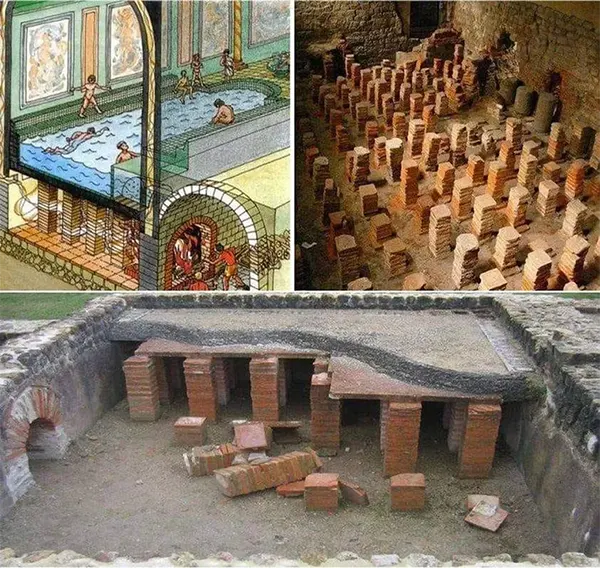

Hypocaust Heating System in Ancient Rome

Heating in ancient Rome reached a similar level of innovation through the hypocaust system, an early form of centralized heating.

Hot air produced in a furnace traveled beneath raised floors and sometimes through wall flues, warming entire bath complexes and public buildings.

This approach ensured consistent indoor temperatures and became one of the earliest large-scale applications of controlled environmental engineering.

A heating system from Ancient Rome.

5,000-Year-Old Anti-Seismic Foundations of Peru

Across the world in Peru, the Caral-Supe civilization developed a seismic-resistant technique more than 5,000 years ago.

Known as shicras, these woven vegetable-fiber baskets filled with stones acted as flexible foundations capable of absorbing and dispersing earthquake energy.

This method demonstrates how ancient societies responded to geological challenges with simple yet remarkably effective solutions.

An ancient anti-seismic foundations of Peru.

Metal Clamps That Held Stone Blocks in Place

The use of metal clamps to secure giant stone blocks is one of the more striking examples of practical engineering in antiquity.

These clamps, often cast in iron or copper alloys, locked masonry pieces together so effectively that many of the structures they supported remain standing after thousands of years.

Their surviving marks offer a quiet lesson in how small components can sustain monumental architecture.

Metal clamps that held stone blocks in place.

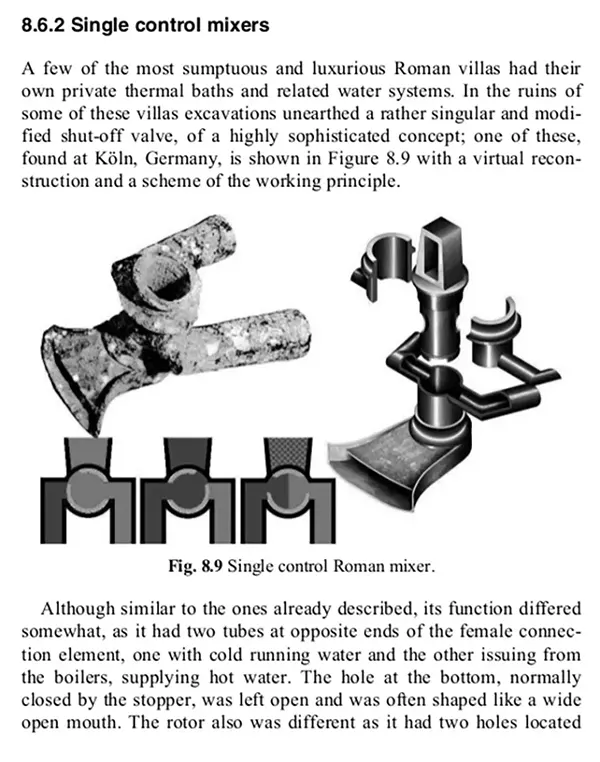

Roman Faucets from Pompeii

Among the most advanced early urban systems was Roman plumbing, represented beautifully by faucets uncovered in Pompeii dating from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE.

These bronze fixtures, known as cannulae, were part of an extensive aqueduct network that delivered water directly into homes, public baths, and fountains.

Roman faucets.

Remarkably, some designs even incorporated single-control mixers, showing a level of sophistication far ahead of their time.

The Snake Bridge on the Macclesfield Canal

Innovation also reshaped transportation systems. Bridge 77 on the Macclesfield Canal, often referred to as the snake bridge, was designed specifically to keep horses hitched to the narrowboats they pulled.

The spiral ramps allowed animals to cross the canal without interrupting their movement, eliminating the need to detach towlines.

This concept later inspired similar split or roving bridges, some built entirely of iron, where a central slot allowed tow ropes to pass through uninterrupted.

The Snake Bridge.

Inca Stone Bridge at Huarautambo

In Peru once again, the Incas demonstrated exceptional resourcefulness with their stone bridges, including the one at the Huarautambo archaeological complex.

Constructed during the reign of Pachakutiq Inka Yupanki, the bridge exemplifies how Andean engineers combined local materials and environmental understanding to create durable infrastructure in mountainous terrain.

An Inca stone bridge.

Roman Pedestrian Crossings in Pompeii

Roman streets also reveal clever design features. Pedestrian crossings in Pompeii, formed by evenly spaced stone blocks, functioned much like modern crosswalks while allowing carts to pass through the gaps.

At night, the so-called “Tiger Eyes”—small white stones placed among paving slabs—reflected any available light to help travelers navigate the roads more safely.

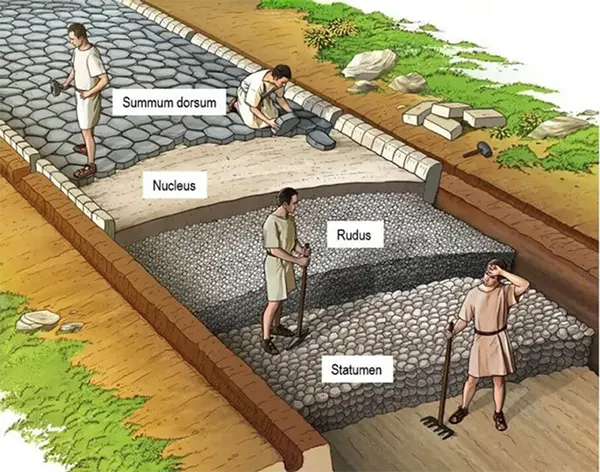

Construction Layers of a Roman Road

These roads were masterpieces in their own right. Roman engineers built nearly 29 major highways branching out from the capital and connected by countless secondary routes.

Their layered construction, with a raised center for drainage and ditches and culverts along the sides, enabled more than 250,000 miles of durable roadways by the 2nd century CE.

Many modern roads still follow these ancient paths, and in some places, the original Roman pavement remains in use.

An illustration of a typical Roman road.

The Sweet Track in Somerset, England

Evidence of early engineering mastery also appears in prehistoric Europe. The Sweet Track, a Neolithic timber walkway built around 3800 BCE in the Somerset Levels of England, provided a stable route across marshlands.

As one of the oldest engineered pathways in the world, it illustrates how early communities adapted their environment long before stone architecture appeared.

The Norias of Hama

Farther east, the Norias of Hama in Syria showcase medieval hydraulic ingenuity. Seventeen enormous waterwheels, some of them the tallest in the world for nearly five centuries, lifted water from the Orontes River for irrigation and urban supply.

Their rhythmic wooden turning became an iconic symbol of the region’s dependence on controlled water flow.

The Norias of Hama.

Roman and Chinese Water Pipes

Aquatic engineering also defined Roman and Chinese infrastructure. Lead pipes in Bath, England—some still functioning after 2,000 years—reveal the Roman commitment to durable water systems.

Roman water pipes.

Meanwhile, ceramic water pipes from the Warring States period in China, dating from the 5th to 3rd century BCE, show a parallel tradition of long-lasting and carefully constructed hydraulic networks.

Chinese water pipes.

Byzantine Geared Mechanical Calendar

Mechanical innovation flourished in the Byzantine Empire as well. A sophisticated geared mechanical calendar, dating from roughly 400 to 600 AD, stands as the second oldest device of its kind after the famed Antikythera Mechanism.

Capable of indicating the time in sixteen locations and calculating the positions of the Sun and Moon, it reflects an advanced understanding of mathematics and astronomy.

Antikythera Mechanism.

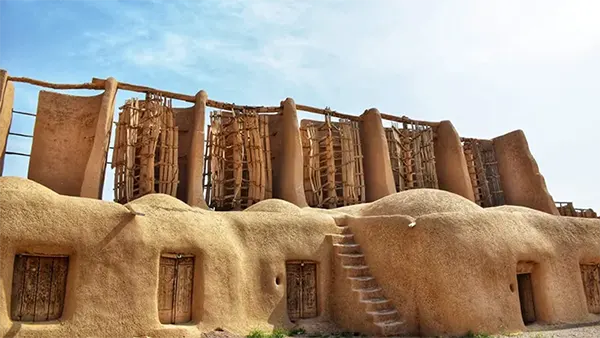

Ancient Windmills of Nashtifan, Iran

In Iran, the ancient windmills of Nashtifan continue to turn after roughly a thousand years. Built from clay, straw, and wood, these vertical-axle machines harness strong desert winds to grind grain, demonstrating a renewable-energy solution developed long before the industrial era.

The Barbegal Watermill Complex

One of the most impressive examples of ancient industrial power is the Barbegal watermill complex in southern France.

Built in the 2nd century CE, this array of sixteen interconnected waterwheels formed what is often considered the first large-scale industrial milling operation in Europe.

With an estimated output of 25 tons of flour per day, it reveals a society capable of organizing machinery on a scale far greater than previously imagined.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / Britannica).