Authored by Charles Davis via The Epoch Times,

For 2,000 years, Asia’s landlocked nations have borne the weight of other people’s ambitions.

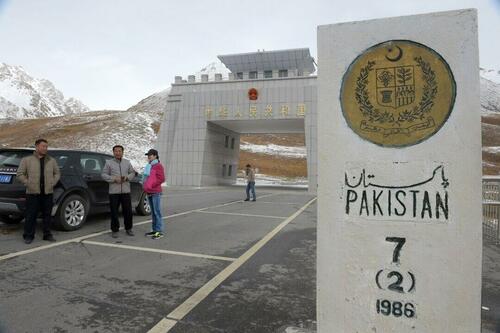

From the camel caravans that picked their way across the Karakoram into Gandhara, to the mule trains that descended through the Khyber Pass toward the Persian plateau, the territories we now call Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan were never just backdrops to the Silk Road.

They were gatehouses—toll points on the flow of goods, cultures, and armies between East and West. Dynasties rose here, funded by the coin of foreign traders; others were crushed under the weight of foreign demands—a pattern that long predated the Haqqani network’s extortion of infrastructure to fund terrorism.

China’s Revival of Imperial Geography

Beijing has an intimate knowledge, having shared much of this history. The ancient Chinese court called the Central Asian trade arteries the “Xiyu”—the “Western Regions”—and dispatched envoys, merchants, and soldiers to secure them.

Centuries later, Kubla Khan’s empire would stretch across much of that terrain, enforcing a form of governance that prized order, tribute, and the protection of trade routes. The Mongol guarantee allowed Silk Road commerce to flourish under imperial watch.

Today, the “Belt” in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a studied revival of this same geography, serving the age of fiber‑optic cables and liquefied natural gas—but with a different ethos.

A Change in Management

Where Khan’s rule offered structure and predictability, communist China’s model leans on opacity, debt leverage, and a security footprint that often outpaces local consent. Long ago, Han‑era emissaries offered silk and lacquerware; now the People’s Republic of China provides concessionary loans, turnkey infrastructure, and the uncertainty that comes with embedded security.

It’s no accident that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s August itinerary stitched together Islamabad and Kabul like beads on a single thread: a landward echo of China’s “string of pearls” strategy in the Indian Ocean, where port investments and naval access points form a maritime chain of influence.

That overland corridor doesn’t just complement the maritime chain—it extends it, giving Beijing parallel lanes to leverage global interests against partner countries’ land and sea needs. A similar corridor is now in development on the South American continent.

Development at a Cost

In Islamabad, Wang stood alongside Pakistani Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar to announce CPEC 2.0, the next phase of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the $60 billion-plus flagship of the Belt and Road.

Official statements emphasized expanding trade, agriculture, and high‑tech parks. Less visible, but just as binding, were the provisions on securing Chinese projects and personnel, a much-needed commitment to restricting militant attacks on CPEC assets, especially from legacy groups like the Haqqani network, which for years extorted from infrastructure projects to fund terrorism.

The announcement came amid record Belt and Road investment figures, with Beijing committing $124 billion in what analysts dubbed a “buying spree” targeting energy transition chokepoints—lithium, rare earths, hydrogen—to consolidate long-term resource leverage over partner nations.

While the official rollout emphasized scale and ambition, the recent collapse of a rail bridge in Qinghai certainly cast a shadow over the BRI’s veneer, exposing the structural fragility and speed‑over‑safety tradeoffs that haunt China’s project delivery model.

Loans for Leverage

Days later, the Chinese delegation was in Kabul, hoping to extend CPEC northward into Afghanistan, through a trilateral engagement with the Taliban government and their Pakistani counterparts. The Taliban, desperate for revenue and recognition, have signaled openness to the deal.

For Beijing, the calculus is colder. Establishing Kabul’s passageway buys a potential transit route into Central Asia, a foothold in Afghanistan’s mineral sector, and—most sensitively—a channel for direct influence along the narrow Wakhan Corridor that touches China’s Xinjiang region.

That last point isn’t ceremonial cartography. For years, Beijing has portrayed the Uyghur issue as an internal matter, but quietly, it has pressed every government on its periphery to surveil, detain, or expel Uyghur exiles and suspected militants. A formal infrastructure partnership with the Taliban offers new leverage to dictate “counter‑terrorism cooperation” on Beijing’s terms, even inside Afghan territory.

Terrorist Turned Interior Minister

In late 2021, Beijing moved beyond polite requests and into transactional coercion. Chinese diplomats in Kabul—acting under instructions tied to prospective CPEC expansion—pressed Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani to locate and hand over Uyghur militants from the Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), branding them a direct threat to the Chinese regime’s grip on Xinjiang.

The message, according to regional officials familiar with the talks, was unambiguous: compliance would garner infrastructure money and political recognition; refusal would be costly in both areas. Almost in parallel, Haqqani was drawn into mediating between Islamabad and the Tehreek‑e‑Taliban Pakistan (TTP) to curb attacks on CPEC assets—a role shaped in part by Beijing’s push to extend the corridor into Afghanistan.

In each case, Beijing was forcing a neighboring government to do what it could not do unilaterally—suppressing non-state actors that challenge the authority of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) by connecting those crackdowns to the flow of Chinese capital.

Final Thoughts

To a casual observer, these moves might look like opportunistic development diplomacy. In a strategic context, they’re something else: the methodical tightening of a belt that’s as much about security corridors as it is about commercial ones. Pakistan’s fiscal fragility and Afghanistan’s diplomatic isolation create an opening that no other major power is willing and able to exploit. Instability, for Beijing, isn’t a deterrent—it’s a justification for presence.

From the terraces of Taxila to the bazaars of Herat, the old Silk Road holds rewards for those who can safely move goods, people, and ideas through it. The danger, as history also shows, is when the custodian of that passage decides that “safety” must serve its own empire first.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

Loading recommendations...