Authored by Uriel Araujo via GlobalResearch.ca,

Hydropolitics has long been an underreported yet decisive force shaping the trajectory of nations. While analysts often emphasize pipelines, rare earths, or grain corridors, it is water — the most fundamental resource — that increasingly determines whether regions move toward cooperation or conflict.

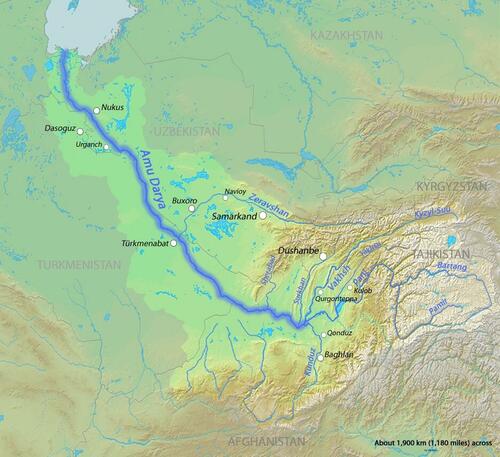

The ongoing development of Afghanistan’s Qosh Tepa Canal illustrates this clearly. As Kabul pushes forward with a project to divert significant volumes from the Amu Darya River, neighboring Central Asian states are sounding alarm bells. Thus far, however, international attention has been curiously muted.

As climate researcher Kamila Fayzieva notes, the canal is a 285-kilometer project capable of irrigating vast tracts of northern Afghanistan. For a nation battered by war and sanctions, it promises food security.

Yet what looks like a lifeline for Afghans could spell disruption for Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, who rely on the Amu Darya’s flow. Water scarcity in Central Asia is already acute enough to threaten livelihoods and stability. Every cubic meter counts. Afghan authorities in any case argue their population cannot be indefinitely deprived of water that technically flows through their territory.

This tension is not unique. Water disputes have become a recurring feature across Eurasia. In South Asia, the Indus Waters Treaty provides a fragile framework between India and Pakistan, yet hydropolitical skirmishes abound. New Delhi has even been accused of weaponizing floods in its dispute with Islamabad, as I’ve commented.

Afghanistan’s case is delicate because: as analyst Syed Fazl-e-Haider reminds us, other than its treaty with Iran (to the West) over the Helmand River, it lacks any comprehensive, formal water-sharing agreement with its northern neighbors regarding the Amu Darya basin. For one thing, despite some limited cooperation, Kabul remains out of the Almaty Agreement. Whereas India and Pakistan at least have the Indus framework, Kabul operates in a kind of legal vacuum. This creates the paradox noted by Fayzieva: the country most in need of water is also the least integrated into governance mechanisms.

Map of the Amu Darya watershed (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The danger is not just environmental but also geopolitical. Central Asia has long been a zone of overlapping influences — Russian, Chinese, Turkish, Iranian, and Western. The Qosh Tepa project risks becoming another wedge issue, exploited by external actors.

In this conundrum, regional institutions hold part of the answer. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is arguably the most obvious candidate to mediate disputes there. It brings together those actors — Russia, China, the Central Asian republics, Iran — who have direct stakes in stability. If Afghanistan, now an observer, in theory, were gradually integrated, a framework for water-sharing could emerge — one that is regionally owned and geopolitically neutral.

The alternative is grim. Without cooperation, each country could pursue unilateral “hydro-sovereignty,” building canals, dams, or diversions regardless of neighbors. Elsewhere, similar trajectories haunt other basins: as I’ve noted before, Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam remains a source of tensions with Egypt and Sudan; Turkey’s GAP project in turn has impacted downstream neighbors. The result is often dangerous escalation.

For the Taliban, seeking international legitimacy as it is, the Qosh Tepa Canal is a showcase project. It signals governance, sovereignty, and food security. Ignoring Afghanistan’s plight is not sustainable for Central Asia; yet neither is acquiescing unconditionally. Dialogue is the only real alternative; engaging with the Taliban is thus the only pragmatic path.

Comparisons with India-Pakistan are illuminating. The Indus Treaty, despite wars, has survived since 1960, showing even bitter enemies can agree on water-sharing. Afghanistan and its neighbors are not enemies; they share culture and trade links. Yet mistrust runs deep, exacerbated by instability.

Crafting a pact under SCO auspices could prevent the canal from becoming a casus belli in future scenarios. Other complementary frameworks may also be considered, such as revitalizing the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS), bilateral accords, or even UNRCCA talks. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation in turn may serve a symbolic role. Meanwhile, China’s Belt and Road Initiative could fund water-efficient technologies, while the CSTO would benefit from integrating water security into its agenda — and so would the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) particularly, since agriculture and trade are directly impacted.

It is always worth stressing the Eurasian dimension. Water disputes do not remain local. Scarcity can fuel migration, terrorism, and state failure.

For instance, no one denies the Syrian conflict was fueled by Western interference — in fact, the US, European powers plus Turkey armed anti-Assad groups, including terrorist factions. Yet the crisis was also partly triggered by prolonged drought in places like Daraa. This should remind us that climate and water are conflict multipliers.

Instability in Central Asia would impact not only Russia and China, but also energy markets, trade corridors, and Europe’s security. Thus, while the Qosh Tepa Canal may appear to be a local Afghan initiative, its reverberations could reshape the Eurasian chessboard to some extent. Regional actors must act before the canal becomes operational enough to render negotiations moot. Preventive diplomacy is always cheaper than conflict management.

In conclusion, hydropolitics is no longer the neglected sibling of geopolitics, so to speak — it is geopolitics itself. The Afghan canal saga highlights how water — the element most taken for granted — remains a strategic variable. Succeeding in transforming this potential flashpoint into an arena of cooperation would not only avert a crisis but also signal that Eurasia can further develop its own mechanisms of resilience, free from the dubious gift of Western assistance (often intertwined with interference as it is). The choice in any case is about either hydrodiplomacy or hydroconflict.

Loading recommendations...