By Tom Teague of The Manhattan

Modern Monetary Theory is a macroeconomic theory developed in the early 1990s. It maintains that governments that issue their own currency are not financially constrained in the same way as households or businesses. According to MMT, governments can create money and spend as they see fit; taxes serve primarily as a tool to control inflation and create demand for the currency. MMT also emphasizes that government spending should aim to ensure full employment.

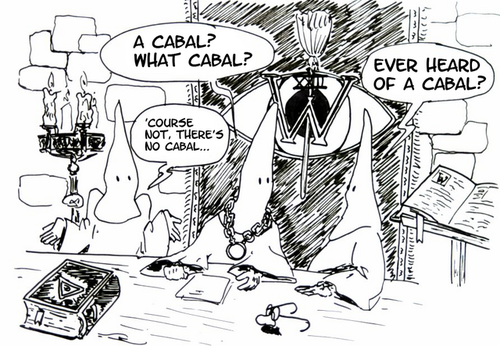

Putatively heterodox to most economists, MMT has often been quietly promoted as a back door to central planning. It is analogous to Critical Race Theory in that it is referenced everywhere, yet often denied when challenged. Although no major central bank has formally adopted it, MMT’s logic aligns with the behavior of many major central banks since the Global Financial Crisis.

During the GFC, the financial system nearly collapsed under excessive leverage to the housing market and a series of black swan events. The aftermath provided a platform for the political left—who had been sidelined by the fall of Communism—to return to power and lay the foundations for a new vision of society. This shift promoted “stakeholder” capitalism: an economy to be guided by elites seeking less greed, greater inclusivity, and more environmental focus. (See the World Economic Forum.)

New rules were implemented for Europe’s financial institutions, particularly insurance companies and pension funds. Post-GFC, European insurers were governed under Solvency II and III. Under these regimes, there was a zero risk-weight for government bonds and large capital charges for corporate bonds, equities, infrastructure, and securitizations. This forced a major reallocation of asset holdings in the insurance sector (which controls €9.5 trillion in assets) toward government bonds, and away from risk assets. Pension funds—managing another ~€10 trillion—were also affected by these regulations and incentivized to shift toward “safe” government bonds, though to a somewhat lesser extent. The result was a significant shift from the private sector to the public sector, greatly benefiting European governments that could now borrow more cheaply. This process arguably helped finance the ‘Great European Project,’ but at the expense of private sector vitality.

This regulatory drift toward government bonds did not stop in Europe. In the U.S., the Dodd-Frank Act and Basel III were implemented, which encouraged banks and other regulated institutions to hold Treasuries rather than risk assets. While these rules had a significant impact on banks’ balance sheets, their effect on insurance companies and pension funds was less direct. Basel III’s risk weightings granted U.S. Treasuries and MBS very low charges, while company loans, equities, private credit, and various securitizations faced 100% or higher risk charges. Notably, the risk weight for equities held on bank balance sheets increased from 100% to 250%.

Basel III’s greatest impact did not come from the risk weights alone, but from higher total capital requirements, new capital buffers, and the liquidity coverage ratio—all of which further favored government bonds and reinforced the preference for “safe assets.” In practice, this crowded out private sector lending and investment, even if risk weights themselves did not always change dramatically.

It is understandable that, following the near-collapse of the financial system, regulators sought to promote stability. Yet, the net effect of these efforts was to encourage lending to governments and discourage lending to the private sector—ironic, given that the crisis was rooted in regulatory failures to prevent excessive leverage in U.S. housing.

In the post-GFC era, governments—enjoying lower bond yields and greater regulatory power—found themselves in a position to expand spending. Using debt to solve problems and bail out economies became the norm. The crucial question is whether this shift was intentional, or merely a byproduct of circumstances. Given recent government agendas to “rebuild capitalism,” focus on climate initiatives, and promote forced equality (including through immigration), it seems unlikely to be accidental.

Government spending relative to GDP has accelerated in recent years. In the U.S., this figure grew from 35% in 2018 to 39.7% in 2024, peaking at 47% in 2020 during Covid (compared to less than 20% pre-GFC). In the EU, government spending hovered around 46.5% of GDP in 2015–2019, and surged to 52.9% during Covid. In Japan, government spending is normally about 40% of GDP and reached 47.1% during the pandemic. We have entered an age where governments use cheap borrowing to centrally plan economies.

A peculiar relationship has now evolved between central banks and governments. As government spending grows, central banks are increasingly tasked with protecting the government’s ability to borrow at low cost, instead of focusing on stimulating the private sector. Ambiguity arises when governments create jobs by expanding already bloated agencies, placing them in competition with the private sector. The result is a zero-sum game between the government and the private sector. Rather than fostering private sector growth, governments and central banks have tilted toward active intervention and control.

In 2017–2018, the Trump administration implemented deregulatory measures and passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, aiming to boost private sector business investment, productivity, and job growth. In response, Chairman Powell raised rates four times in 2018, moving the Fed Funds rate from 1.5% in March to 2.5% by December. The Fed’s rationale was to preempt inflation from an overheating economy—even as core inflation hovered near the 2% target. By Q4 2018, fears of tightening led to a major stock market correction.

In the past year, global bond yields have increased as markets become less tolerant of central planning and begin to price in weaker growth. German Bund yields have moved from 2.1% to 2.75% on the 10-year. In Japan, the 10-year JGB yield has climbed from 0.75% to 1.64%. Investors are realizing: 1) government spending is not effectively growing the economy (if it ever intended to), and 2) underinvestment in the private sector, due to energy costs, regulation, and offshoring, has eroded growth potential. Ultimately, the private sector must generate the taxes that service government debt.

Enter the Scully Curve: an economic concept positing a relationship between government spending (relative to GDP) and economic growth. The curve, named after Gerald Scully, argues for an optimal spending level—typically 24–32% of GDP for industrialized economies. For each additional 1% of government spending above this range, GDP growth may decrease by 0.1–0.2%; if spending rises to 45–50% of GDP, a 0.5–1.5% reduction in growth can be expected. This weakening of the private sector ultimately leads to doubts about debt repayment and undermines the argument that “the government can do it better.”

Central banks, often in concert with fiscal authorities, may now raise rates to combat inflation resulting from deficit spending—which in turn lifts borrowing costs for businesses, crowds out private investment, and distorts market signals. Studies from the post-2008 period reveal that sustained high rates in Europe suppressed private sector recovery and channeled capital into sovereign bonds.

MMT was a prescriptive idea for more central planning, and it has left a profound mark on government debt markets and private sector growth in the West. Now, as economies confront a world of high spending and low growth, there is increasing urgency to reverse course. Populist leaders, most notably Trump, are calling for shrinking government and deregulation to unleash pent-up private sector demand. The U.S., uniquely among major economies, may still have the capacity to grow out of the MMT legacy.

Loading recommendations...