Cards on the table: I hate the term 'metroidbrania'. I think many people who use the term seem to hate it, too; as Kate Gray writes on a Nintendo Life feature listing some of these games, the word "makes [her] feel like someone with a hobby so dorky that [she] can't talk about it with normal people."

I'd put it forth that the term doesn't just sound dorky, and it's not just hard to explain (given that first you have to explain what a metroidvania is – itself a fraught bit of terminology). I'd say it's all but useless, too. If you duckduckgo for 'metroidbrania', the main results are three listicles that'll give you the following corpus of games:

- Outer Wilds

- Return of the Obra Dinn

- The Sinking CIty

- Sherlock Holmes (as in the whole Frogwares series)

- Heaven's Vault

- The Forgotten City

- Overboard!

- Her Story, Telling Lies

- Sorcery! (???)

- Tunic

- The Witness

- A Monster's Expedition

- Animal Well

- Myst

- Blue Prince

- Antichamber

- Leap Year

- Taiji

- Gone Home (!???!?)

- Rain World

- Fez

- Chants of Sennaar

You'll never convince me that these games form a coherent genre, or even that you can group them under a general umbrella term. At best, most of those are what I'd call "thinky games" – a broad aggregation of deduction, knowledge, and puzzle games that would include everything from Zork to Myst to cryptic crosswords to Ultros.

I think the reason why is that the term was originally coined to mean "games with open-ended exploration" – similar to a metroidvania – but using knowledge gating instead of traditional ability gating. In a "true" metroidbrania, what you know is the only real form of progression; a player who already knows all the secrets can start a fresh save and immediately go through the motions of beating the game, skipping over most of the game.

The problem there is that there's very few games that actually meet this description. Out of the list above, the only ones I'd put in that list are Animal Well, Outer Wilds, and Tunic. Because there's not enough games to put on a listicle, the term naturally expands so you can at least name 10. Because everyone is doing this independently, it expands in every available direction, until somehow Gone Home and Fez are now in the same genre. 'Metroidbrania' is thus dead on arrival; it can never usefully describe a game beyond a vague sense that it involves knowledge, puzzles, or deduction.

I like the more neutral and obvious term "thinky game" to refer to the whole aggregate of knowledge, deduction, and puzzle games as a whole; it doesn't purport to be a coherent genre, just a general descriptor (in the same way that "action game" is). But I think we need better language to talk about some of those emerging mechanical ideas in the space of and around knowledge games, specifically.

I'm also setting puzzle games aside in this essay – that's a whole large set of games unto itself, and I also don't want to distract with the question of how to best use that descriptor – ie, whether adventure games that involve puzzles (eg, Myst) are 'puzzle games' as such.

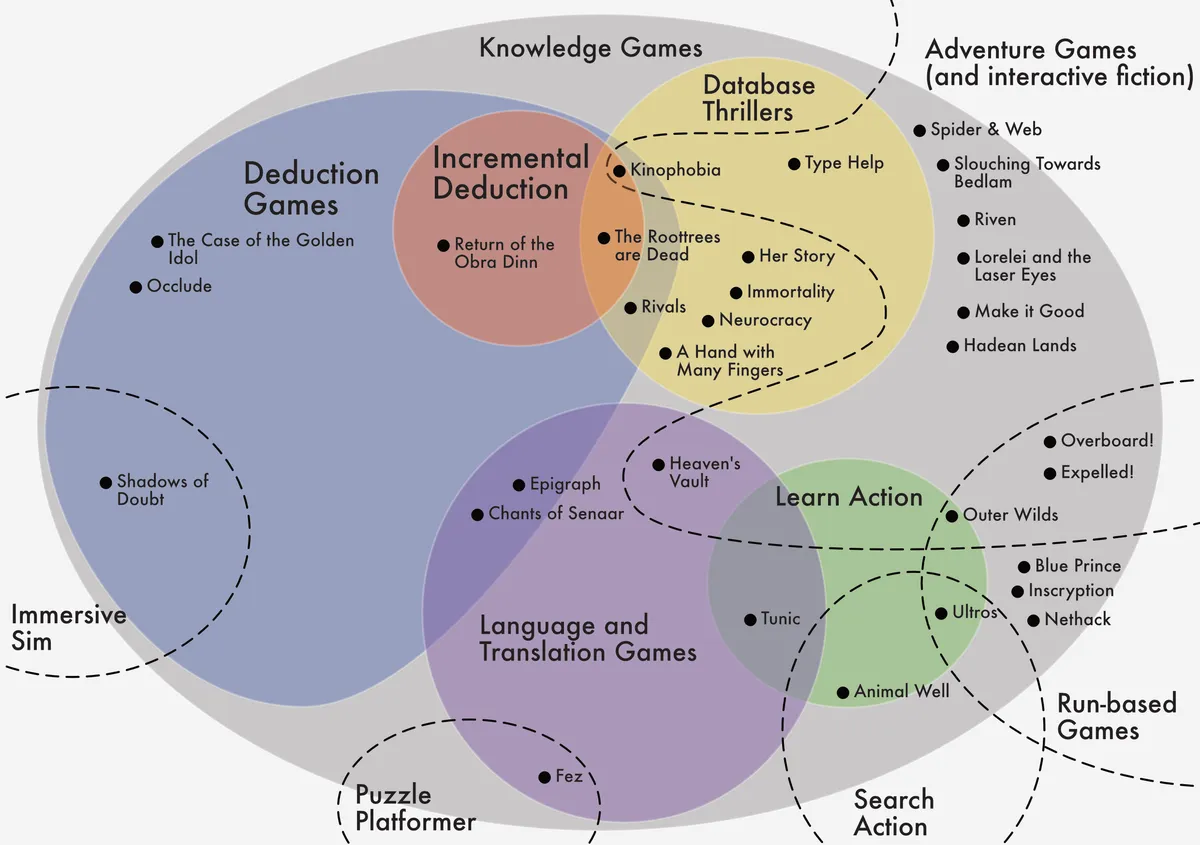

So, considering knowledge and deduction games, I ended up sitting down and drawing a diagram to suss out the relationships between them.

Knowledge games

A knowledge game is a game where the player's knowledge is a central resource and progression mechanic. This is a really broad category, but it encompasses most of what gets referred to as a 'metroidbrania':

- Knowing words to search for in Her Story;

- Understanding the events of the voyage in Obra Dinn;

- Knowing how to use the game's affordances in Animal Well;

- Understanding the secret language in Tunic.

For this term to be useful, I think we have to separate knowledge as in explicitly-encoded information that the game contains, from insights that the player accrues by gradually experimenting with a system – otherwise, every classical puzzle game (eg, Portal, Stephen's Sausage Roll) is now a knowledge game.

Knowledge games tell you things, even if they ask you to make significant leaps of logic with the information they present – as in Animal Well, where some of the critical knowledge has to be arrived at by analogy, by seeing things in the environment and relating them to the player’s affordances.

A few other typical features of knowledge games:

- Players are asked to build an internal model of a narrative or system, rather than just internalizing discrete bits of information. For example, The Case of the Golden Idol asks players to reconstruct sequences of events.

- Knowledge is useful more than once and/or far away from the site where it's gained. In Animal Well, learning the "secret" affordances is useful throughout the game, for example; the final level in Case of the Golden Idol asks the player to understand the full story, not just the events of that single level.

- Knowledge is a central resource – in a 'pure' knowledge game, the only resource. So, for example, an immersive sim having a post-it note telling you that the password is 451 does not have the knowledge game nature.

Knowledge gating

Knowledge gating is the mechanic where some section of the game is accessible to any player who has the requisite knowledge. This is where the whole comparison with metroidvanias comes from – the idea that player knowledge acts at the "key" to the one of the game's "locks", in the same way that in a traditional metroidvania you might use a double jump to get up on a previously-inaccessible ledge.

Knowledge gating is almost universal to knowledge games, if you define it broadly. The Case of the Golden Idol, for example, is structured like a typical puzzle game – there are levels that have to be solved in order. But since every single level is solved by first learning information and then deploying it, we could say it's a knowledge-gating game. I didn't bother including a circle for it in the diagram because you could argue that it would be completely contiguous with the "knowledge game" circle; counterexamples very much welcome.

But we can narrow the idea down somewhat to consider knowledge gating in the context of games that have some kind of movement or exploration affordance that is itself distinct from navigating a semantic space. Games in which knowledge unlocks areas or affordances in the context of a play space; so, for example, Outer Wilds or Animal Well, but not Return of the Obra Dinn or pure database games like Her Story.

Under that consideration, for there to be a knowledge gate, there has to be some contrasting form of movement or progression that isn’t purely driven by the player accruing knowledge or exploring a semantic space. I’d say things like the various secrets in Blue Prince qualify, for example.

Learn action

'Search action' is a calque of a Japanese term that refers to the same thing as 'metroidvania'. It's increasingly preferred by Western fans of the genre for its relative historical neutrality, especially as the genre expands more and more beyond its originators – there hasn't been a new search action Castlevania in a long time now.

By analogy, 'learn action' is a term I'm trying to stick as a narrowly-defined version of 'metroidbrania', with the benefit of not sounding terrible. This is a set of games that pretty much just includes knowledge games that are also open-level exploration games; examples would include Animal Well, Tunic, Ultros, and Outer Wilds. Some of those games have the combination of combat, exploration, and platforming that characterizes a 'core' search action game, while others don't. I'm treating 'exploring a physical space' as central to this conception of a genre – again, setting aside games with more linear structures or games without movement mechanics at all.

Database thrillers

A database thriller is a game where searching for information out of a database or archive is a central affordance. Usually this takes the form of a web search box – as in Her Story and The Roottrees are Dead, but it doesn't have to. For example, Immortality uses a web of metaphorical or literal connections between objects on screen; A Hand with Many Fingers uses an old-school index card catalog system. My own database thriller KINOPHOBIA has searches that are mediated by texting an NPC.

I call these database thrillers rather than the more neutral database game to point at a commonality in games using this structure: they're more or less always mystery or intrigue stories, but also I don't believe anyone has made one that squarely falls in the actual genre of crime fiction. So, thriller it is. Maybe I'll make one where you trawl a police archive to solve cold cases.

Deduction games

A deduction game is one on which:

- The player is asked to make inferences or determine some underlying truth from incomplete information or suggestive clues;

- Progression is made through the player proving that their deductions are correct.

That is, deduction can't merely happen as part of the narrative, it is a central mechanic of the game. A game like Disco Elysium, in which you play as a detective, isn't necessarily a deduction game.

The idea of a deduction obviously points towards the detective and mystery genre but critically, it doesn't have to. Occlude, for example, is an occult-themed puzzler built around deducing the rules to a mysterious card game from observing its behavior; The Roottrees Are Dead is a genealogical-research game that asks you to reconstruct a large and sprawling family tree.

More or less every deduction game has to find some answer to the question of how to avoid guessing and lawnmowering without making the game frustrating or stumping players. Generally this is done by having a broad possibility space of how players could answer a deductive question. At the basest level, you can think of the answers in Clue: Colonel Mustard did it in the parlor with the candlestick. Case of the Golden Idol, for example, makes the player answer a whole batch of questions at once; it'll tell you if you're very close but off on a couple of details – which players can somewhat abuse to essentially extract a hint from the system – but it won't let players test each assumption once in isolation to guess their way through the game.

Incremental Deduction

A particular subset of deduction games, these are games that make use of the mechanic popularized by Return of the Obra Dinn: the game only confirms your conjectures once you get enough of them right at once. But the game also largely doesn't impede your progress merely for getting one deduction wrong.

This is basically one very elegant and very successful anti-guessing mechanic. Particularly, the game never jumps at the chance to tell you that you're wrong, which both avoids discouraging players but also avoids leading them. If you have three outstanding conjectures in Obra Dinn but the game hasn't confirmed them, you can't be sure whether you got one wrong or all three. And you can choose to try to keep going and make more conjectures to see if you can "lock" some of the existing set, or you can go back and revise your assumptions about what you've put down already. It's a system that is at once forgiving of players' mistakes but also that demands that they eventually circle back to resolve those mistakes.

Language and Translation Games

This is the last of these categories that I want to talk through – games with constructed languages that the player is expected to learn. I'd split these into two subsets: ones that are also deduction games, in which the player has to specifically prove language proficiency to progress (the most prominent example probably being Chants of Sennaar) and ones in which the language is more a part of the body of knowledge that the player acquires (as the cypher in Tunic). Because cyphers and constructed languages are a common feature of puzzles, language and translation will crop up in all kinds of thinky games here and there; Case of the Golden Idol, for example, has its 'Lemurian' sigils. I've restrained myself to only listing games that really focus on this language aspect under that blob.

Of course – the diagram above is naturally incomplete, boundaries are debatable, and genre words are only an imperfect scheme to try and understand art. But I thought this survey was useful to work through as an exercise in gleaning the beginning of a landscape – a set of featural relationships between games that we can use to talk about them more usefully than lumping all of those different games under one genre term. Especially if the genre term sounds as bad as 'Metroidbrania'.

Ultimately the goal here is not necessarily to be the last word on the subject but to just name some useful landmarks that others can use to triangulate, or as grounding for a critique – are these labels useful? What other corners of the knowledge-game landscape can we identify?

Or perhaps even: what undiscovered space is implied by the shape of the landscape as it's been marked out already?