Authored by Mercura Wang via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder that gradually destroys memory, thinking skills, and the ability to perform everyday tasks. As the single most common neurodegenerative disease, it affects more than 6 million Americans—most of them age 65 or older. The disease is irreversible and fatal.

It often begins subtly—years before it’s diagnosed—showing up as everyday lapses that are easy to brush off.

Alzheimer’s symptoms develop differently depending on when the disease begins.

There are generally two types: early-onset Alzheimer’s, which develops before age 65, and late-onset Alzheimer’s, which occurs afterward.

Early-onset Alzheimer’s accounts for about 5 percent to 6 percent of cases, often has a stronger genetic link, progresses more quickly, and may start with problems in thinking, language, or vision rather than memory alone, making it harder to diagnose initially.

Late-onset Alzheimer’s, which starts after age 65, typically begins with gradual memory loss and progresses slowly through predictable stages.

The following five stages describe the progression of late-onset Alzheimer’s, the most common form of the disease.

1. Asymptomatic Stage

Biological changes characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease are present long before cognitive or behavioral symptoms appear. This stage may last for years or even up to two decades.

2. Early Stage

Early-stage Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by mild symptoms that may resemble normal aging difficulties. People at this stage are typically aware of their condition and remain largely independent, able to drive, work, and engage in daily activities with minimal assistance.

Common warning signs include:

- Frequently misplacing items and being unable to retrace steps

- Confusion about time, dates, or familiar places

- Difficulty with planning or organizing

- Trouble learning new information or maintaining focus

- New challenges in finding the right words in conversation or writing

- Difficulty interpreting visual information

- Personality or emotional changes

3. Middle/Moderate Stage

This stage is marked by more noticeable symptoms. Memory and cognitive abilities continue to decline, and people often require greater supervision and assistance with everyday activities, although some mental clarity remains. This stage can persist for many years.

Common symptoms include:

- Difficulty performing daily activities, including dressing, driving, reading, or writing

- Trouble remembering recent events or important personal experiences

- Confused speech or incorrect word use

- False beliefs or hallucinations

- Mood changes, including depression, agitation, or aggressive behavior

- Withdrawal from social interactions

- Repetitive or compulsive actions

- Sleep disturbances

- Impaired spatial awareness

4. Severe/Late Stage

This stage is characterized by profound cognitive and physical impairment, requiring constant assistance with daily activities.

Common symptoms include:

- Severe memory loss, including the inability to recognize family members or familiar faces

- Loss of the ability to communicate

- Loss of bladder and bowel control

- Difficulty swallowing

- Progressive weakness and reduced mobility

- Potentially violent behavior

- Unintentional weight loss

- Recurrent infections

- Episodes of delirium

5. End-of-Life Stage

During this stage, the person is in the final months of Alzheimer’s disease and loses all functional independence. Cognitive decline is severe, requiring round-the-clock care, with a focus on palliative support and maintaining comfort and quality of life. Ultimately, the condition can lead to coma and death, often as a result of infections or organ failure.

Signs of Rapid Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease

Rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease is a recognized clinical subtype of Alzheimer’s distinguished by unusually fast cognitive deterioration and a markedly shorter survival. It often advances over months to a few years, with people showing steep declines in global cognition and daily functioning.

Alzheimer’s is a complex condition resulting from multiple interacting processes in the brain. Its causes have always been considered a set of hypotheses.

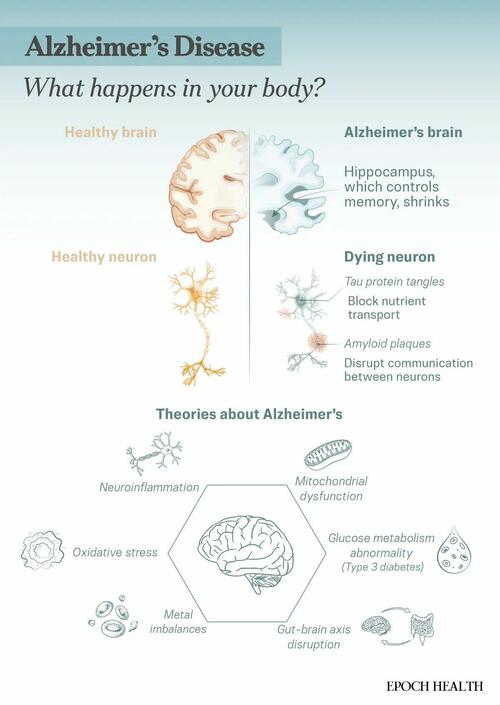

A common hypothesis is that the disease involves abnormal accumulations of two proteins: amyloid and tau. Amyloid forms sticky plaques around brain cells. These plaques keep neurons from communicating, while tau forms tangles inside brain cells, blocking nutrient transport.

These protein abnormalities disrupt cell signaling, are toxic, and eventually lead to neuron death. As neurons die, brain regions shrink, with memory-related areas often affected first.

However, this hypothesis—the most well-known one—has also been implicated in research fraud and study manipulation.

In recent years, scientists have come up with many new theories:

- Neuroinflammation: In Alzheimer’s disease, brain immune cells (microglia) can become overactive, triggering chronic inflammation that damages neurons and promotes the spread of toxic proteins.

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mitochondria fail to produce enough adenosine triphosphate or ATP, the cell’s energy fuel, while releasing harmful molecules that damage neurons.

- Glucose Hypometabolism: The brain becomes resistant to insulin and can’t use glucose properly—sometimes called “Type 3 diabetes“—which disrupts cell signaling and promotes toxic protein buildup.

- Gut-Brain Microbiota Axis: An unhealthy gut microbiome can trigger body-wide inflammation that reaches the brain, damages the protective blood-brain barrier, and contributes to neurodegeneration.

- Metal Imbalances: Abnormal accumulation or deficiency of metals such as copper, iron, or zinc can promote oxidative stress, protein misfolding, and neurotoxicity.

- Excess Glutamate: Overactivation of glutamate receptors (excitotoxicity) can lead to sodium and calcium overload and neuronal death, particularly in memory-related brain regions such as the hippocampus.

- Cholinergic Neuron Damage: Damage to cholinergic neurons, which produce acetylcholine—a neurotransmitter essential for memory and attention–can contribute to early cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Oxidative Stress: The brain’s high oxygen use and mitochondrial activity increase exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS). In Alzheimer’s disease, excessive ROS and impaired antioxidant defenses cause lipid, protein, and DNA damage, while amyloid beta both accumulates and further promotes oxidative stress.

- Blood-Brain-Barrier Disruption: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a vascular pathology linked to Alzheimer’s disease, involves the deposition of amyloid-beta in the walls of small cerebral blood vessels. This impairs blood flow, disrupts blood-brain barrier integrity, and promotes neuroinflammation.

- Pathological Proteins: Misfolded amyloid-beta and over-phosphorylated tau accumulate to form plaques and tangles that disrupt synaptic function, neuronal transport, and overall brain network stability.

- Brain Structure Changes: Progressive loss of brain tissue—especially in the hippocampus and cortex—reflects widespread neuron death and worsening symptoms.

Risk Factors

Age is the strongest risk factor, with the chance of developing Alzheimer’s roughly doubling every five years after age 65. Age-related brain changes—such as shrinkage, inflammation, blood vessel damage, and impaired cellular energy—can harm neurons and disrupt the function of other brain cells. Women have a slightly higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than men, possibly because women tend to live longer.

The risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease is approximately two times higher for black and Latino populations than for white populations.

Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

Lifestyle habits and environmental exposures play an important role in brain health and may influence the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

- Social Isolation: Social isolation increases the risk of dementia by up to 60 percent.

- Lack of Mental Stimulation: Low cognitive activity can accelerate mental decline, whereas mentally stimulating work is associated with a lower risk of developing dementia later in life.

- Chronic Stress: Chronic stress leads to prolonged elevated cortisol levels. High cortisol can damage the hippocampus, impair neuronal plasticity, promote neuroinflammation, and accelerate amyloid beta and tau pathology.

- Lack of Sleep: Poor or insufficient sleep may contribute to protein buildup. Most people benefit from six to eight hours of uninterrupted sleep each night.

- Unhealthy Diet: Diets high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats may raise the risk of Alzheimer’s disease by contributing to cardiovascular problems, reduced blood flow to the brain, and neuroinflammation.

- Lack of Exercise: Regular physical activity supports heart health, blood flow, and oxygen delivery to the brain, which helps maintain cognitive function.

- Excess Belly Fat: Excess abdominal fat, particularly visceral fat, promotes chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, vascular dysfunction, hormonal imbalances, and oxidative stress—all of which contribute to brain atrophy and cognitive decline.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Lack of certain micronutrients—such as manganese, selenium, copper, and zinc, and vitamins A, B, C, D, and E—may increase Alzheimer’s risk. People with Alzheimer’s disease have also been found to have lower brain levels of lutein, zeaxanthin, and lycopene.

- Exposure to Pollutants: Higher exposure to fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) is linked to more severe Alzheimer’s-related brain changes and greater dementia severity because these tiny particles can travel into the bloodstream and the brain, where they trigger chronic inflammation and oxidative stress.

- Exposure to Environmental Toxins: A 2020 review found that infections caused by viruses, bacteria, or fungi can trigger inflammation, which may gradually shrink brain tissue and contribute to Alzheimer’s disease.

- Nighttime Light Exposure: Greater exposure to outdoor light at night is linked to a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease, especially in people under 65, because it disturbs the body’s natural circadian rhythm, increases inflammation, and weakens disease resistance.

- Smoking: Smoking damages blood vessels and reduces blood flow to the brain, with studies suggesting a 30 percent to 50 percent increased risk of dementia. Quitting smoking, even later in life, can lower this risk.

Genetics

Both types of Alzheimer’s disease have significant genetic components, although they are driven by different underlying causes, ranging from direct gene mutations to a complex mix of genetic and environmental risk factors.

- PSEN1 or PSEN2 Genes: Early-onset Alzheimer’s can sometimes be inherited, known as familial Alzheimer’s disease, caused by mutations in the APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes. These mutations lead to the overproduction of amyloid beta, which accumulates into amyloid plaques in the brain.

- APOE Gene: The APOE gene is a well-known risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s. A 2024 study found that people with two APOE4 genes almost always showed Alzheimer’s-related brain changes by age 55, and most developed abnormal amyloid levels by age 65.

Medical Conditions and Intervention

Certain medical conditions and the ways they are managed can affect cognitive health and may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease risk.

- Certain Conditions: Diabetes, hearing loss, brain injury, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and certain infections may increase Alzheimer’s risk.

- Certain Medications: Examples include zolpidem (for insomnia) and benzodiazepines (for anxiety), as they can impair cognitive function, leading to memory loss, reduced verbal memory, and slowed processing speed.

There is no single test for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. Specialists diagnose it with about 95 percent accuracy by ruling out other conditions. Confirmation is only possible after death through autopsy. Comprehensive evaluations—including medical history, neurological exams, and other diagnostic procedures—are essential.

Assessment Methods

Several tools and evaluations help doctors assess memory, thinking, and overall brain function when diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.

Physical and Neurological Exams

They check overall function, muscle tone, strength, vision, and hearing.

Cognitive Assessments

Brief mental status exams to evaluate memory, thinking, and concentration by using short, structured tasks that measure cognitive skills.

- Mini-Mental State Examination: Uses tasks such as identifying dates, naming objects, following simple commands, and recalling short lists

- Mini-Cog: Uses a three-word recall test and a clock-drawing exercise to assess memory and executive function

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment: Uses tasks that assess attention, memory, language, visuospatial skills, and executive function to provide a more sensitive, broad evaluation

Brain Imaging

Brain imaging tests create detailed pictures of brain structure and activity to identify changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

- CT Scan: Creates cross-sectional images of the brain

- MRI Scan: Generates detailed images to reveal brain shrinkage

- PET Scan: Visualizes brain activity and detects molecular changes, including brain metabolism, protein deposits, inflammation, and chemical activity

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory tests analyze bodily fluids to detect biomarkers and rule out other conditions that can resemble Alzheimer’s disease.

- Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap): Collects cerebrospinal fluid to assess protein levels

- Blood Tests: Measure proteins and biomarkers linked to brain changes, including early Alzheimer’s pathology

- Urinalysis: Checks for infections or other abnormalities

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, so treatment focuses on slowing its progression, managing symptoms, and adapting the home environment to simplify daily activities.

1. Medicines

Medications for Alzheimer’s disease aim to reduce beta-amyloid protein levels in the brain and help manage behavioral issues, although their overall benefits may be modest, and some drugs remain controversial regarding safety and effectiveness. Doctors typically begin Alzheimer’s treatment with low doses and gradually increase them based on tolerance.

Medications for Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease

Medicines used in the early stages of Alzheimer’s aim to support memory, thinking, and daily functioning.

- Cholinesterase Inhibitors: These medicines may help manage cognitive and behavioral symptoms by preventing the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that supports communication between neurons, although their effectiveness declines as the disease progresses. Examples include galantamine, rivastigmine, benzgalantamine, and donepezil.

- Immunotherapy Drugs: These medicines target beta-amyloid to reduce brain plaques and have been shown in early-stage patients to slow cognitive decline and lower amyloid levels. Examples include lecanemab and donanemab.

Medications for Moderate to Advanced Alzheimer’s Disease

Medicines used in the later stages of Alzheimer’s focus on easing symptoms and supporting quality of life.

- Memantine: This medicine can help reduce symptoms and allow people to maintain certain daily functions, such as using the bathroom independently, for longer. It regulates glutamate, which in excess can damage brain cells, and can be combined with cholinesterase inhibitors for added benefit.

- Brexpiprazole: This atypical antipsychotic is approved to manage agitation associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Medications to Use With Caution

The following medications should be used only after a doctor reviews their risks and side effects, when safer nondrug options have been ineffective, and with careful monitoring by both the person with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers.

- Sleep Aids: These medicines should generally be avoided, as they can increase confusion and the risk of falls.

- Anti-Anxiety Medications: Some medicines, such as benzodiazepines, can cause drowsiness, dizziness, falls, and increased confusion.

- Anticonvulsants: These medicines can cause drowsiness, dizziness, mood changes, and confusion.

- Antipsychotics: These medicines are prescribed to treat hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, agitation, and aggression, but may have serious side effects, including an increased risk of death in some older people with dementia.

2. Cognitive Therapies

Cognitive therapies involve structured activities and strategies designed to stimulate thinking, memory, and problem-solving, while supporting daily functioning and emotional well-being.

- Cognitive Stimulation Therapy: This therapy involves engaging in activities to improve memory, language, and problem-solving skills, often in a group setting that also encourages social interaction.

- Cognitive Rehabilitation: A specialist and a support person work together to develop strategies for managing daily tasks, aiming to use healthy brain functions to support weaker areas, and to provide a sense of accomplishment.

- Reminiscence and Life Story Work: These therapies focus on long-term memories, skills, and positive experiences to boost mood and well-being. Reminiscence uses prompts such as photos or music to recall the past, while life story work creates a personal record of someone’s life.

3. Neuroprotective Herbs

Certain herbs show potential for supporting brain health and may help reduce processes linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

- Ashwagandha: The extract withaferin A may help reduce the buildup of harmful brain proteins and lower inflammation and oxidative stress. A randomized controlled trial of 40 adults with mild cognitive impairment used 250 milligrams of ashwagandha extract per day for 60 days and reported improvements in memory and attention.

- Turmeric: Turmeric contains curcumin, a natural compound with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that support brain health. Research suggests it may help slow Alzheimer’s progression by reducing brain plaques and preventing the buildup of harmful beta-amyloid proteins.

- Sage: Sage extract may help support mood, cognition, and cholinergic function. One study tested a fixed dose of sage extract (60 drops/day) for four months in people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and found it effective.

4. Acupuncture

Acupuncture may help support brain function in Alzheimer’s disease at both molecular and systemic levels by improving symptoms and the brain’s microenvironment, especially when applied early. Research suggests it works through multiple pathways, including reducing beta-amyloid deposits, improving tau protein changes, and easing neuroinflammation.

A 2019 meta-analysis of 13 studies found that acupuncture can improve memory and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease, and in many cases, it has been more effective than conventional Western medicines, with fewer adverse effects. Despite its potential, acupuncture is not yet widely used in clinical Alzheimer’s treatment.

5. Apitherapy

Honey bee products may help support brain health in Alzheimer’s disease.

Royal jelly, a creamy substance produced by worker bees and fed to queen bees, has shown promising neuroprotective and memory-boosting effects in multiple preclinical studies by helping brain cells survive, reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, improving energy regulation, and limiting damage from harmful proteins such as amyloid-beta.

6. Emerging Treatments

Researchers are exploring new treatments that may slow Alzheimer’s disease by targeting underlying biological changes.

- Lithium Treatment: A study published in August found that lithium levels in the brain’s prefrontal cortex—important for memory and decision-making—dropped by more than half in people with Alzheimer’s disease. A meta-analysis found that lithium treatment may help slow cognitive decline and support thinking and memory in people with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Sodium Benzoate Treatment: This common food preservative has shown potential benefits for Alzheimer’s disease by supporting cognitive function. It appears to enhance brain cell communication by preserving D-serine, a chemical messenger needed for learning and memory, and may also reduce oxidative stress, which contributes to Alzheimer’s progression.

Managing Alzheimer’s disease relies on regular social engagement, physical exercise, proper nutrition, consistent health care, and a calm, structured environment.

1. Games

Using play as an intervention strategy for people with dementia provides notable cognitive, emotional, and social benefits. A 2022 study found that caregivers observed improvements in energy levels, mood, communication, and connection through customized play activities.

2. Music

A 2023 systematic review of eight studies found that music therapy improves cognitive function in people with Alzheimer’s disease, with particularly strong effects seen in active music interventions where people participate in music-making. These findings support music therapy as a promising complementary approach. A study published in July also found that exposure to Mozart’s K.448 rhythm improved cognitive function in mice.

3. Dance

A 2019 review of 12 studies found that dancing can improve physical, cognitive function, and psychological well-being in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Most studies showed that dance either enhanced or slowed the decline in quality of life for both patients and caregivers.

4. Brain-Boosting Foods and Diets

Eating brain-supportive foods may help protect memory and overall brain health. Whole grains and legumes provide steady energy for neurons. Fruits such as berries, grapes, watermelon, and avocados supply antioxidants, resveratrol, and lycopene that protect against memory loss. Dark leafy greens and beets support circulation and reduce inflammation, while seafood and shellfish provide omega-3s and vitamin B-12 for cognitive function.

Nuts and olive oil offer healthy fats that support vascular health. Seeds such as pumpkin, sunflower, and sesame are rich in vitamin E and other key nutrients essential for brain health.

Sesame seeds, in particular, contain tyrosine, which boosts dopamine production, as well as zinc, vitamin B6, and magnesium—nutrients that help keep the brain sharp and alert.

The specific diets that people with Alzheimer’s disease may benefit from include:

- Mediterranean Diet: This diet emphasizes vegetables, fruits, whole grains, beans, nuts, olive oil, and frequent fish intake while limiting red meat and processed foods. It may help slow Alzheimer’s progression.

- MIND Diet: This diet combines elements of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets and emphasizes green leafy vegetables, berries, whole grains, beans, nuts, fish, and olive oil, while limiting red meat, sweets, cheese, butter, and fried foods.

5. Nutritional Supplements

Some vitamins and minerals may help support brain health and address deficiencies linked to cognitive decline.

- Selenium: Research shows that people with Alzheimer’s disease have lower levels of selenium in their blood compared to healthy older people.

- Zinc: Early clinical trials suggest that zinc therapy may help people with Alzheimer’s disease by lowering harmful copper levels and possibly improving cognition.

- B Vitamins: A 2022 meta-analysis of 95 studies found that vitamin B supplementation may help slow the rate of cognitive decline.

6. Aerobic and Resistance Exercises

Regular physical activity—such as walking, gardening, cooking, or playing sports—can help slow cognitive decline and may delay the progression of dementia.

Combining aerobic and strength exercises with everyday activities such as walking, dancing, and gardening supports brain health and general well-being. Try to aim for at least 30 minutes of activity, five days a week, to boost circulation and brain health.

7. Sufficient Sleep

Deep, restorative non-REM slow-wave sleep helps protect the brain against beta-amyloid. Research shows a strong connection between Alzheimer’s progression and the circadian system—the body’s internal clock that controls sleep, wakefulness, and other daily cycles. The circadian system regulates the activity of about half of the 82 genes associated with Alzheimer’s risk.

8. Meditation

Meditation may support brain health and could help prevent or even reverse cognitive decline. Research shows that people who meditate experience less hippocampal atrophy—a reduction in the size of the hippocampus, which controls memory formation, learning, and spatial navigation—and report less isolation and loneliness, which are linked to higher Alzheimer’s risk. Meditation may also improve sleep, lower blood pressure, and reduce cardiovascular disease risk, further supporting overall brain and body health.

9. Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy, which uses plant-based essential oils through inhalation or skin application, may help improve thinking and memory in people with Alzheimer’s disease, as essential oils possess neuroprotective and antiaging properties.

Several recommended essential oils include:

- Lavender: Calms mood and may reduce depression, anger, and irritability

- Lemon Balm: Eases anxiety and insomnia, and may support memory

- Ylang-Ylang: Helps relieve depression and may improve sleep

- Bergamot: Reduces anxiety, agitation, and stress, and may support sleep

10. Other Considerations

Although not treatments, these approaches play a vital role in supporting the well-being of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Safety and Supportive Measures: The environment should be bright, cheerful, and secure, with moderate stimulation such as a quiet TV or radio to avoid overwhelming the person. Maintaining structure and routine for daily tasks such as eating, bathing, and sleeping helps with orientation, provides a sense of stability, and can improve sleep. Regularly scheduled activities, both physical and mental, support independence and engagement, and can be simplified into smaller steps as dementia progresses.

- Long-Term Care: Specialized long-term care facilities provide trained staff, structured routines, meaningful activities, and safety features.

The progression of Alzheimer’s disease is unpredictable. On average, patients live about seven years after diagnosis, although the disease course can vary widely, lasting anywhere from one to 25 years. Most people who lose the ability to walk survive no longer than six months, but life expectancy differs from person to person.

Read the rest here...

Loading recommendations...