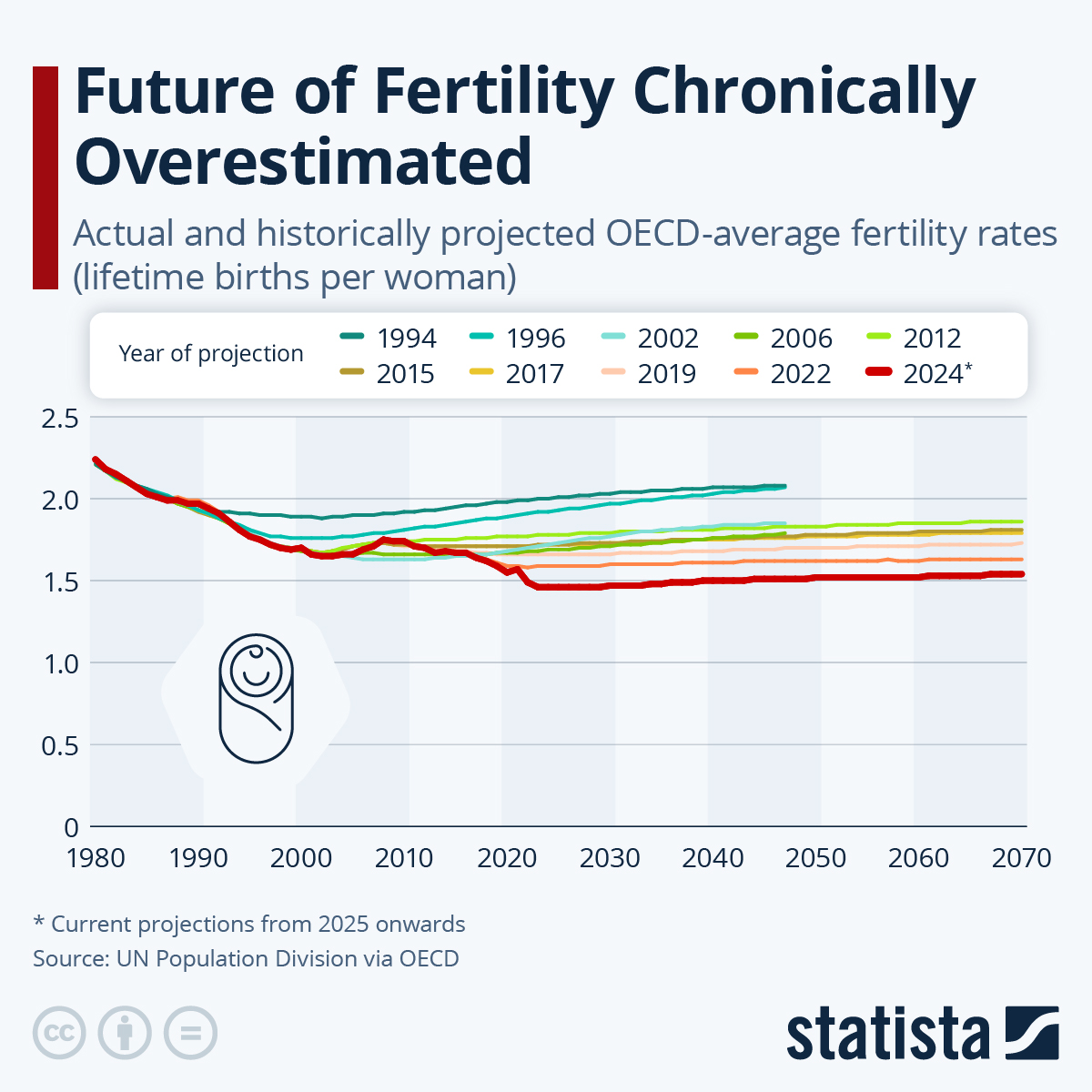

The newly released OECD Pensions at a Glance report shows how fertility projections have been wrong again and again over the years, grossly underestimating how much fertility would decline each time.

As fertility rates and pension funds are intrinsically tied, this can cause problems down the line, when incoming payments from workers to pension funds are smaller than expected and payouts to current pensioners exceed them.

As Statista's Katharina Buchholz shows in the following data, the lifetime births per woman in OECD countries sank from 2.2 in 1980 to 1.9 in 1994.

You will find more infographics at Statista

At the time, demographers estimated that the rate would recover up to around 2.1 by the middle of the upcoming century.

By 2002, births rates had declined to 1.66, yet a recovery to 1.85 by 2047 was once again expected.

By 2012, there was actually a slight recovery back up to 1.75 births per women, prompting demographers to expect the number of births to rise to an average of 1.8 per woman by 2050.

Yet, birth rates started to fall again to below 1.5 by 2024, the latest year on record.

Still, the tale of recovering fertility has not been eliminated, as birth numbers are currently projected to rise again, albeit only slightly, to 1.52 by 2050 and 1.54 by 2070.

Many scientists now see the official UN demographic forecasts as conservative estimates and believe that the world population will actually shrink significantly faster than they project.

A 2020 study published in The Lancet actually calculates that contrary to what UN figures say the world population will have shrunk by 2100 and could potentially already be significantly lower than it is today.

While population growth has been studied at length and models in this field tend to be more reliable, less work has been done on the newer topic of population decline, making calculations more unreliable.

Loading recommendations...