Why do we care about next-frame prediction or next-token prediction as pretraining tasks? Because they are simple objectives that require models with very little built-in knowledge to learn how the world works directly from data. Pretraining reduces uncertainty about what comes next in a sequence—whether that’s a frame or a word. As that uncertainty drops, intelligent capabilities begin to emerge.

This is easy to see with language. Given only “=”, next-token prediction is ill-posed. Given “2+3=”, the next token is nearly deterministic. Train a language model on enough of these sequences and the predictions become low-entropy. Some capabilities emerge from scale alone, but others only appear once training sequences are long enough to include the information needed to resolve uncertainty.

Learning not just video, but the actions that shape it

The same logic applies to world models. To predict the next observation, a world model has to infer the underlying state of the world and how that state evolves over time. In practice, the best source for this is large-scale, general video. This pushes the model to learn structure about physics, causality, and persistence.

Learning long horizons and hidden state

This becomes especially clear in long-horizon settings. Imagine someone starts running a bath, leaves the room for several minutes, and then comes back. While the bath is out of view, the water level continues to rise, the temperature changes, and the tub may eventually overflow. To make a sensible prediction when the person returns, the model has to maintain an internal state of the world and reason about how that state evolved while it was unobserved.

There are a few ways we believe to get this behavior. One is to build in explicit mechanisms for memory or state tracking. The other is to train on sequences long enough that remembering and updating hidden state is required to reduce predictive uncertainty. Short sequences don’t force this: if forgetting carries no cost, long-term structure won’t be learned.

If we want world models that learn the world observation-by-observation—and remain coherent over tens of minutes or hours—we need training data and training procedures that span those horizons. We’ve already seen how this plays out in language: extending context length and improving sequence modeling unlocked capabilities that were not apparent at shorter horizons. World models are earlier on the same trajectory. As data, architectures, and training algorithms are pushed to longer temporal scales, we should expect similar step-changes in their ability to represent persistent state, causality, and long-horizon dynamics. This is incredibly exciting.

The limits of hand-crafted simulators

Simulation is about predicting how a system’s state evolves over time, using models, data, or both. In the limit, one could imagine simulating the world from first principles, down to elementary particle interactions. In practice, this is only feasible for very small systems today.

Most real-world simulations today narrow the problem considerably. Specialized, hand-crafted models capture just enough structure to reproduce a particular behavior, while irrelevant detail is ignored or averaged away. This makes simulation tractable, but also constrains each simulator to a specific domain and a fixed set of assumptions. For example, a rigid-body physics engine is not useful for simulating weather.

As systems become more complex, these limitations become more pronounced. Many real-world phenomena are impractical to simulate accurately from explicit rules alone, and building reliable simulators demands significant human effort.

Learning to simulate the world from video

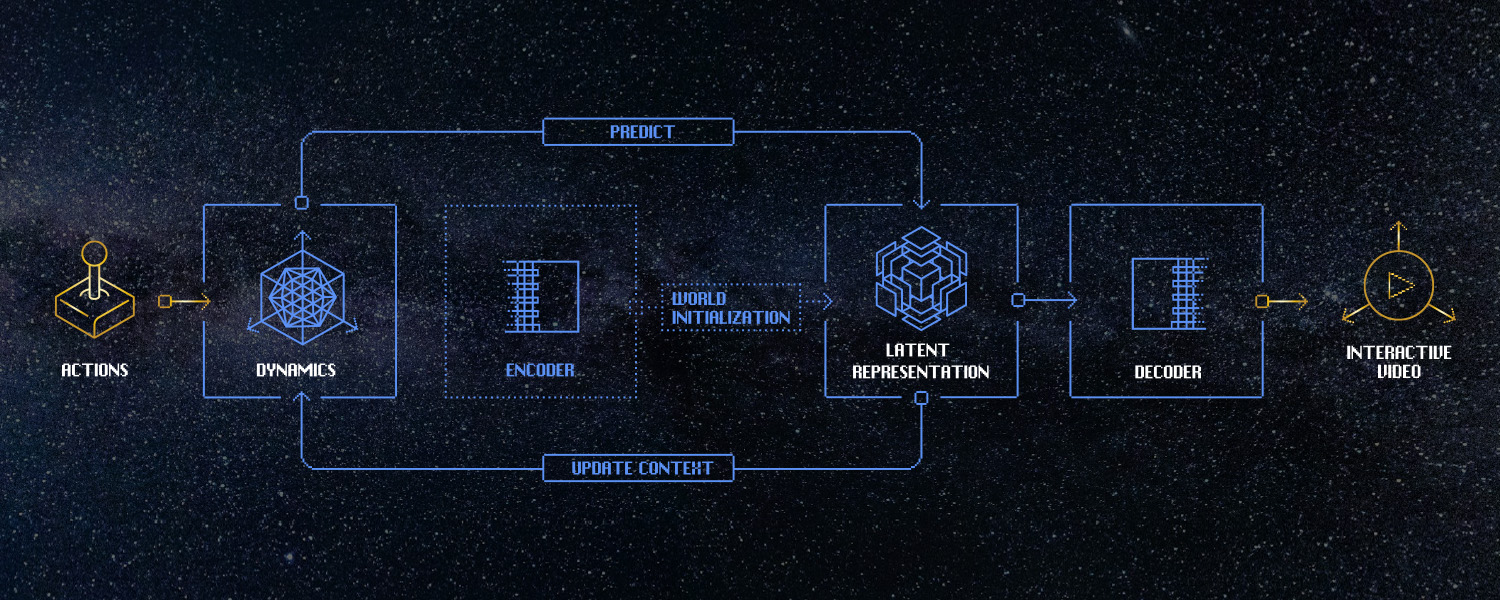

World models approach simulation from a new perspective. Rather than designing a simulator for each domain, we train general-purpose, causal models on large amounts of video and interaction data, and task them with predicting what happens next. Because the data reflects how the world evolves over time, frame-by-frame, the learning problem is inherently causal. Through next-frame prediction, the model learns internal representations of state, dynamics, and interactions without those structures needing to be specified in advance.

This changes how simulation scales. Traditional simulators fix their level of detail up front and incur increasing cost as fidelity rises. World models operate under a fixed computational budget and learn how to allocate capacity dynamically, focusing on the latent structure that most reduces predictive uncertainty. Over time, this allows a single model to cover a broader range of phenomena with far less manual intervention. Odyssey-2 is an early example of this.