"You're taking on a giant. What gives you the audacity?"

On November 5th, 2025, Groq CEO Jonathan Ross was asked why he was even bothering to challenge Nvidia. He didn't blink:

"I think that was a polite way to ask why in the world are we competing with Nvidia, so we're not. Competition is a waste of money; competition fundamentally means you are taking something someone else is doing and trying to copy it. You're wasting R&D dollars trying to do the exact same thing they've done instead of using them to differentiate."

49 days later, Nvidia paid $20 billion for Groq's assets and hired Ross along with his entire executive team.

Except this wasn't actually an acquisition, at least not in the traditional sense. Nvidia paid $20 billion for Groq's IP and people, but explicitly did NOT buy the company. Jensen Huang's statement was surgical: "While we are adding talented employees to our ranks and licensing Groq's IP, we are not acquiring Groq as a company."

That phrasing is the entire story. Because what Nvidia carved out of the deal tells you everything about why this happened.

Forget the AI doomer takes about a bubble forming, lets look into the actual reasons.

What Nvidia Actually Bought (And What It Didn't)

Nvidia acquired:

- All of Groq's intellectual property and patents

- Non-exclusive licensing rights to Groq's inference technology

- Jonathan Ross (CEO), Sunny Madra (President), and the entire senior leadership team

Nvidia explicitly did NOT buy:

- GroqCloud (the cloud infrastructure business)

GroqCloud continues as an independent company under CFO Simon Edwards. This is Nvidia's largest acquisition ever (previous record was Mellanox at $7B in 2019), and they structured it to leave the actual operating business behind. That doesn't happen by accident.

LPU vs TPU vs CPU: Why SRAM Matters

To understand why Nvidia paid anything for Groq, you need to understand the architectural bet Ross made when he left Google.

CPUs and GPUs are built around external DRAM/HBM (High Bandwidth Memory). Every compute operation requires shuttling data between the processor and off-chip memory. This works fine for general-purpose computing, but for inference workloads, that constant round-trip creates latency and energy overhead. GPUs evolved from graphics rendering, so they're optimized for parallel training workloads, not sequential inference.

TPUs (Google's Tensor Processing Units) reduce some of this overhead with larger on-chip buffers and a systolic array architecture, but they still rely on HBM for model weights and activations. They're deterministic in execution but non-deterministic in memory access patterns.

LPUs (Groq's Language Processing Units) take a different approach: massive on-chip SRAM instead of external DRAM/HBM. The entire model (for models that fit) lives in SRAM with 80 TB/s of bandwidth and 230 MB capacity per chip. No off-chip memory bottleneck. No dynamic scheduling. The architecture is entirely deterministic from compilation to execution. You know exactly what happens at each cycle on each chip at each moment.

This creates massive advantages for inference:

- Llama 2 7B: 750 tokens/sec (2048 token context)

- Llama 2 70B: 300 tokens/sec (4096 token context)

- Mixtral 8x7B: 480 tokens/sec (4096 token context)

And 10x better energy efficiency because you're not constantly moving data across a memory bus.

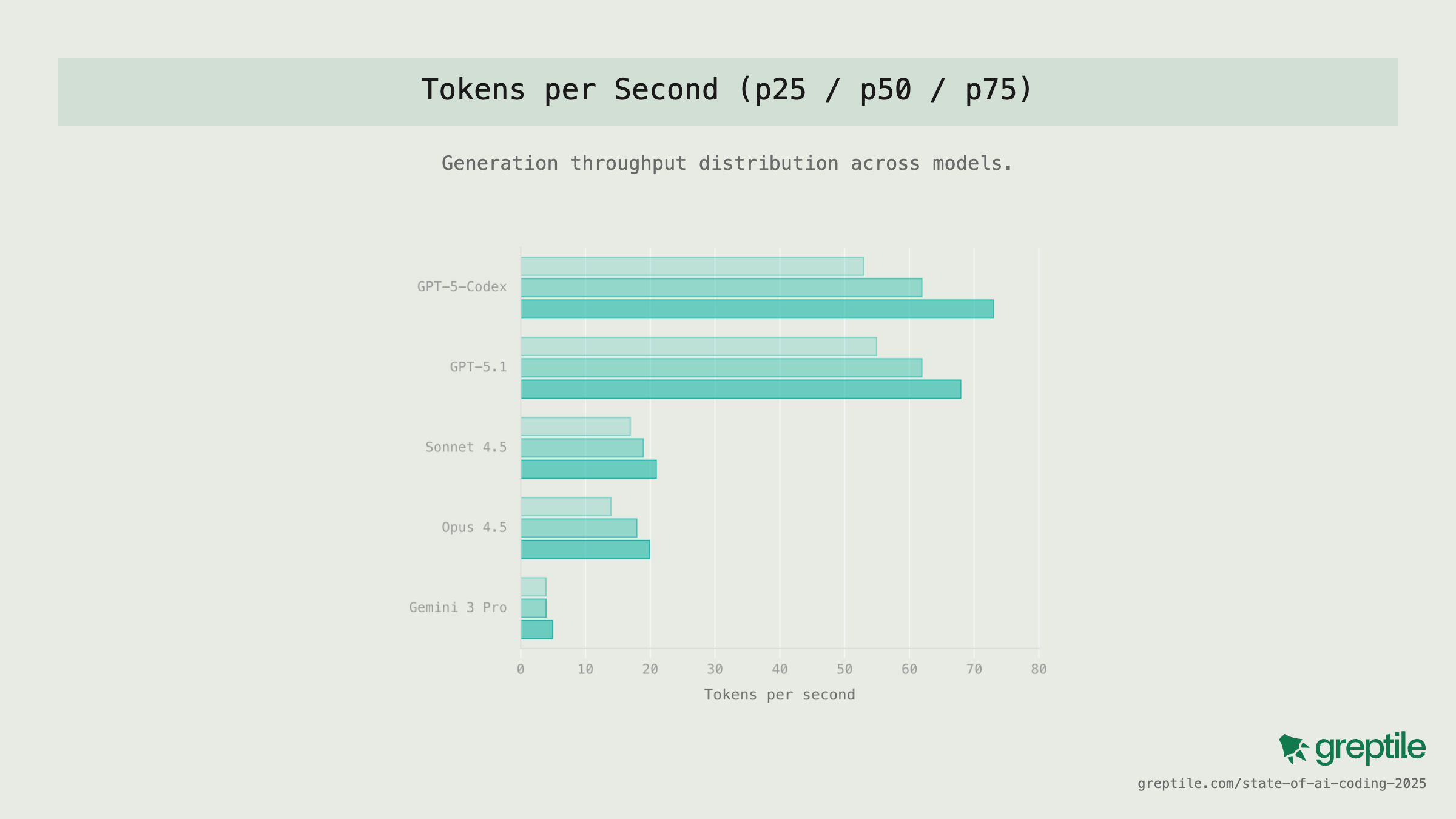

Compare this to SOTA model tokens/sec throughput on GPU inference

Compare this to SOTA model tokens/sec throughput on GPU inference

Serious trade off though, only 14GB of SRAM per rack means you can't run Llama 3.1 405B. And LPUs can't train models at all. This is an inference-only architecture with limited model size support.

But here's what makes this interesting: if DRAM/HBM prices continue climbing (DRAM has tripled in a year I should've gone all in DRAM in Jan I'm done with indexes), and if inference becomes the dominant AI workload (which it is), SRAM-based architectures become economically compelling despite the size limitations. Most production AI applications aren't running 405B models. They're running 7B-70B models that need low latency and high throughput.

The $13.1B Premium and the Non-Traditional Structure

Groq raised $750 million in September 2025 at a post-money valuation of $6.9 billion. Three months later on Xmas Eve, Nvidia paid $20 billion through a "non-exclusive licensing agreement" that acquired all IP and talent while explicitly NOT buying the company.

That's a $13.1 billion premium (3x the September valuation) for a company valued at 40x target revenue (double Anthropic's recent 20x multiple) with slashed projections (The Information reported Groq cut over $1B from 2025 revenue forecasts).

The structure is the story. Traditional M&A would trigger:

- CFIUS review (given Saudi contracts)

- Antitrust scrutiny (Nvidia's dominant position)

- Shareholder votes and disclosure requirements

- Multi-year regulatory review

Non-exclusive licensing bypasses all of it. No acquisition means no CFIUS review. "Non-exclusive" means no monopoly concerns (anyone can license Groq's tech). No shareholder votes, minimal disclosure.

But in practice: Nvidia gets the IP (can integrate before anyone else), the talent (Ross + team can't work for competitors now), and the elimination of GroqCloud (will likely die without IP or leadership). The "non-exclusive" label is legal fiction. When you acquire all the IP and hire everyone who knows how to use it, exclusivity doesn't matter.

The question isn't just why Nvidia paid $13.1B more than market rate for technology they could build themselves (they have the PDK, volume, talent, infrastructure, and cash). The question is why they structured it this way.

The $13.1B premium bought five things a traditional acquisition couldn't:

-

Regulatory arbitrage: Non-exclusive licensing avoids years of antitrust review. Structure the deal as IP licensing + talent acquisition, and regulators have no grounds to block it. This alone is worth billions in time and certainty.

-

Neutralizing Meta/Llama: The April 2025 partnership gave Groq distribution to millions of developers. If Llama + Groq became the default open-source inference stack, Nvidia's ecosystem gets commoditized. Kill the partnership before it scales.

-

Eliminating GroqCloud without inheriting Saudi contracts: Nvidia has invested in other cloud providers. GroqCloud was a competitor. Traditional acquisition would mean inheriting $1.5B worth of contracts to build AI infrastructure for Saudi Arabia, triggering CFIUS scrutiny. The carve-out kills GroqCloud while avoiding geopolitical entanglement.

-

Political access: Chamath makes ~$2B (Social Capital's ~10% stake). Sacks looks good (major AI deal under his watch as AI Czar). Nvidia gets favorable regulatory treatment from the Trump administration. Timing it for Christmas Eve ensures minimal media scrutiny of these connections.

-

Preempting other acquirers: Ross invented Google's TPU. If Google had acquired Groq and brought Ross back, they'd have the original TPU creator plus LPU IP. Amazon and Microsoft were also exploring alternatives to Nvidia GPUs. Better to pay $20B now than compete with Ross at Google/Amazon/Microsoft later.

Two speculative reasons worth considering:

-

Blocking Google/Amazon/Microsoft from partnering with Groq: Both are developing custom AI chips (Trainium, Maia). If either had hired Ross + team or licensed Groq's tech, Nvidia's inference dominance faces a real challenger. If Google had acquired Groq and brought Ross back, they'd have the original TPU inventor plus LPU IP.

-

Chiplet integration for future products: Nvidia might integrate LPU as a chiplet alongside GPUs in Blackwell or future architectures. Having Ross's team makes that possible. You can't integrate IP you don't own, and you can't build it without the people who invented it.

That's how business works when regulation hasn't caught up to structural innovation. Nvidia paid $6.9B for technology and $13.1B to solve everything else using a deal structure that traditional antitrust can't touch.

The Saudi Arabia Problem

In February 2025, Saudi Arabia committed $1.5 billion to expand Groq's Dammam data center. The publicly stated goal was supporting SDAIA's ALLaM, Saudi Arabia's Arabic large language model. The actual goal was Vision 2030: positioning the Kingdom as an AI superpower.

Groq built the region's largest inference cluster in eight days in December 2024. From that Dammam facility, GroqCloud serves "nearly four billion people regionally adjacent to the KSA." This isn't API access. This is critical AI infrastructure for a nation-state, funded by the Public Investment Fund, processing inference workloads at national scale.

According to Ross in the Series E announcement, Groq powers Humain's services including the Humain chat product and supported OpenAI's GPT-OSS model release in Saudi Arabia. Groq operates 13 facilities across the US, Canada, Europe, and the Middle East. Ross noted that capacity expanded more than 10% in the month before the funding announcement and all of that capacity was already in use. Customers were asking for more capacity than Groq could satisfy.

That creates a CFIUS (Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States) problem. A U.S. chip company, venture-backed by American investors, building sovereign AI capability for Saudi Arabia. If Nvidia had acquired GroqCloud outright, they would inherit those contracts and the regulatory scrutiny that comes with them. Foreign investment reviews, export control questions, congressional inquiries about why an American company is providing cutting-edge AI to a Middle Eastern monarchy.

By carving out GroqCloud, Nvidia gets the technology and the talent without the geopolitical mess. The Saudi contracts stay with Edwards and the independent GroqCloud entity. Clean separation. No CFIUS entanglement.

Who Actually Gets Paid (And Who Gets Left Behind)

The Financial Times reported that "despite the loss of much of its leadership team, Groq said it will continue to operate as an independent company." That's corporate speak for: executives and VCs are cashing out while regular employees watch the company they built get hollowed out.

Here's how the $20B probably breaks down (we'll never know the exact numbers since Groq is private and this isn't a traditional acquisition):

Who definitely wins:

VCs (Chamath, BlackRock, Neuberger Berman, Deutsche Telekom, etc.): They own equity in Groq Inc. Depending on how the deal is structured, they get paid based on their ownership percentage. Social Capital's ~10% stake (after dilution) is worth $1.6-2.4B. BlackRock, Neuberger Berman, and other Series E investors get their cut. They're protected regardless of structure.

Executives joining Nvidia (Ross, Madra, senior leadership): They get:

- Retention packages from Nvidia (likely massive given the $20B deal size)

- Sign-on bonuses

- Accelerated vesting of any unvested Groq equity

- New Nvidia equity compensation packages

- Their existing Groq equity gets paid out at the $20B valuation

Jensen Huang's email to Nvidia staff (obtained by the FT) said they're "adding talented employees to our ranks." When you're talent important enough to be mentioned in a $20B deal, you're getting paid.

Who might get paid (depending on deal structure):

Regular Groq employees with vested equity: This is where it gets murky. There are three possible scenarios:

Scenario 1: The IP licensing fee goes to Groq Inc. If the $20B (or a significant portion) is structured as a licensing fee paid to Groq Inc. for the IP rights, that money gets distributed to all shareholders based on ownership percentage. Employees with vested stock options or RSUs get their pro-rata share. This is the best case for employees.

Example: Engineer with 0.01% fully vested equity gets $2M ($20B × 0.01%). Not bad for an engineer who's been there since 2018-2020.

Scenario 2: Most of the $20B goes to retention packages If the deal is structured so that the bulk of the money goes to retention/hiring packages for Ross, Madra, and the senior team joining Nvidia, with a smaller licensing fee to Groq Inc., employees get less. Maybe the split is $15B retention, $5B licensing fee. Now that same engineer with 0.01% gets $500K instead of $2M.

Scenario 3: The IP licensing is separate from talent acquisition Nvidia pays Groq Inc. for the IP (say $5-7B, roughly the Sept 2024 valuation), and separately pays Ross + team retention packages directly. Regular employees get their share of the IP licensing fee only. That same engineer might get $500-700K.

The critical question: Is the $20B figure the total cost to Nvidia (including retention packages), or is it just the IP licensing fee? If it's total cost and most goes to retention, regular employees get scammed.

Who definitely gets done over:

Employees staying at GroqCloud: These are the people who:

- Weren't important enough to be hired by Nvidia

- Have equity tied to GroqCloud's future value

- Just watched their CEO, President, and entire engineering leadership leave

- Are now working for a company with no IP rights, no technical leadership, and no future

Their equity is worthless. GroqCloud will wind down over 12-18 months. They'll either get laid off or jump ship to wherever they can land. They built the LPU architecture, contributed to the compiler stack, supported the infrastructure, and got nothing while Chamath made $2B.

The All-In Connection

This gets messier when you look at who was involved. Chamath Palihapitiya, through Social Capital, led Groq's initial $10 million investment in 2017 at a $25 million pre-money valuation. Social Capital secured 28.57% of the company and a board seat for Chamath.

David Sacks, Chamath's co-host on the All-In podcast, became Trump's AI and Crypto Czar in late 2024. In July 2025, Sacks co-authored "America's AI Action Plan," a White House strategy document positioning AI as a matter of national security. The plan called for exporting "the full AI technology stack to all countries willing to join America's AI alliance" while preventing adversarial nations from building independent AI capabilities.

Two months later at the All-In Summit in September 2025, Tareq Amin (CEO of HUMAIN, Saudi Arabia's state-backed AI company) presented Groq as "the American AI stack in action." This was seven months after the $1.5B Saudi deal.

Sunny Madra, Groq's President and COO, was actively promoting the All-In narrative during this period. He appeared on the All-In podcast in March 2024 to provide a "Groq update" and joined Sacks on "This Week in Startups" in November 2023. When Anthropic raised AI safety regulation concerns in October 2025, Madra publicly sided with Sacks, suggesting "one company is causing chaos for the entire industry" and echoing Sacks's accusation that Anthropic was engaged in "regulatory capture."

So you have Sacks pushing an "America First" AI policy from the White House while Chamath's portfolio company (where Madra is President) is building AI infrastructure for Saudi Arabia. Then Groq gets presented at the All-In Summit as an example of American AI leadership. Three months later, announced on Christmas Eve when media coverage is minimal, Nvidia pays $20 billion to clean up the geopolitical contradiction.

Chamath walks away with $1.6B to $2.4B. Sacks gets a major AI deal under his watch. Nvidia gets favorable regulatory treatment and eliminates multiple problems. The timing ensures minimal scrutiny of these connections.

Chamath's $2 Billion Win vs. His SPAC Graveyard

After dilution from raising $1.7 billion across Series C, D, and E rounds, Social Capital's stake in Groq was probably 8-12% by the time of the Nvidia deal. At a $20 billion exit, that's $1.6 billion to $2.4 billion.

Chamath after using you as exit liquidity and bankrolling it into a 200x win for himself

Chamath after using you as exit liquidity and bankrolling it into a 200x win for himself

Why do I hate Chamath?

Let's look at the sh he dumped on retail with his abysmal SPAC track record:

- IPOA (Virgin Galactic): -98.5% since inception

- IPOB (Opendoor): -62.9% (was -95% before a brief spike)

- IPOC (Clover Health): -74.4%

- IPOE (SoFi): +46% (still underperformed S&P 500's +86%)

Chamath personally dumped $213 million of Virgin Galactic stock before it crashed, using PIPE structures that let him exit while retail investors stayed locked up. In October 2025, when launching a new SPAC, he posted a warning telling retail investors not to buy it: "these vehicles are not ideal for most retail investors."

The Groq bet was classic venture capital: concentrated bet on an exceptional founder (Jonathan Ross, the engineer who invented Google's TPU) building non-obvious technology. Social Capital's 2017 internal memo projected a "High" exit scenario of $3.2 billion. They landed within range despite dilution.

But retail investors never got access to deals like Groq. They got Virgin Galactic. LOL.

To Conclude

Nvidia paid $20 billion for a company valued at $6.9 billion three months earlier, structured the deal to avoid traditional M&A oversight, killed the cloud business without inheriting Saudi contracts, and enriched the exact people (Chamath, Sacks) who spent the last year promoting "American AI leadership" while cutting deals with foreign governments. The employees who built the technology either got hired by Nvidia or have been utterly shafted.

This was fun to look into. If you have any questions or comments, shout me.