Training gaming agents is an addictive game. A game of sleepless nights, grinds, explorations, sweeps, and prayers. PufferLib allows anyone with a gaming computer to play the RL game, but getting from “pretty good” to “superhuman” requires tweaking every lever, repeatedly.

This is the story of how I trained agents that beat massive (few-TB) search-based solutions on 2048 using a 15MB policy trained for 75 minutes and discovered that bugs can be features in Tetris. TLDR? PufferLib, Pareto sweeps, and curriculum learning.

Speed and Iteration

PufferLib’s C-based environments run at 1M+ steps per second per CPU core. Fast enough to solve Breakout in under one minute. It also comes with advanced RL upgrades like optimized vectorized environments, LSTM, Muon, and Protein: a cost-aware hyperparameter sweep framework. Since 1B-step training takes minutes, RL transforms from “YOLO and pray” into systematic search, enabling hundreds of hyperparameter sweeps in hours rather than days.

All training ran on two high-end gaming desktops with single RTX 4090s. Compute was sponsored by Puffer.ai, thanks!

The Recipe

- Augment observations: Give the policy the information it needs.

- Tweak rewards: Shape the learning signal and adjust weights.

- Design curriculum: Control what the agent experiences and when.

Network scaling comes last. Only after exhausting observations, rewards, and curriculum should you scale up. Larger networks make training slower; nail the obs and reward first. Once you do scale, the increased capacity may (or may not) reach new heights and reveal new insights, kicking off a fresh iteration cycle.

Sweep methodology: I ran 200 sweeps, starting broad and narrowing to fine-tune. Protein samples from the cost-outcome Pareto front, using small experiments to find optimal hyperparameters before committing to longer runs.

2048: Beating the Few-TB Endgame Table

2048 strikes a unique balance between simplicity and complexity. The rules are trivial: merge the same tiles to reach 2048, or 131,072. But the game is NP-hard with a massive state space. Random tile spawns (2s or 4s in random positions) force agents to develop probabilistic strategies rather than memorizing solutions.

The previous state-of-the-art search solution uses a few terabytes of endgame tables to reach the 32,768 tile reliably and the 65,536 tile at an 8.4% rate (repo).

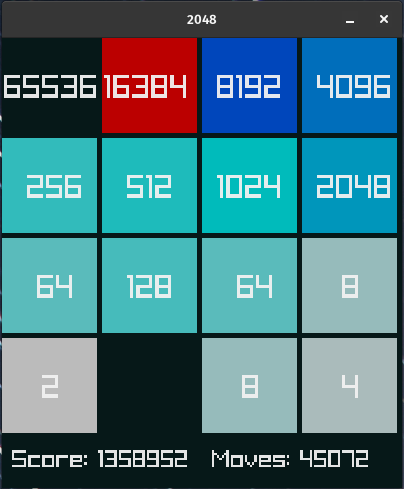

My 15MB policy achieved a 14.75% 65k tile rate and a 71.22% 32k tile rate (115k episodes). Here is the training log. You can play it in your browser here.

What Made It Work

Details are in g2048.h. Obviously, these didn’t come from one shot. Guess how many?

Observation design (18 features per 4×4 cell): These were fixed early and did not change.

- Normalized tile value (raised to power 1.5 via lookup table for speed).

- Empty cell flag (one-hot).

- Tile value one-hots (16 features for 2^1 through 2^16).

- One “snake state” flag (indicating if the board matches the ideal “snake pattern”).

Reward structure: Details were tweaked frequently.

- Merge rewards: Proportional to tile value (weight: 0.0625).

- Penalties: Invalid moves (-0.05) and Game Over (-1.0).

- State rewards: Bonuses for filled top rows and max tiles in corners.

- Monotonicity rewards: Encourage specific directional patterns (weight: 0.00003).

- Snake rewards: Large bonus for the pre-defined snake configuration. I experimented with the length of the snake, and settled with the sorted top row + the max_tile_in_row234 in the second row right. For example, top row: 14-13-12-11, second row: ()-()-()-10.

Curriculum was the key. To learn, agents must experience high-value states, which are hard (or impossible) for untrained agents to reach. The endgame-only envs were the final piece to crack 65k. The endgame requires tens of thousands of correct moves where a single mistake ends the game, but to practice, agents must first get there. Curriculum was manually curated and tweaked repeatedly.

- Scaffolding curriculum (episode-level): Spawns pre-placed high tiles (8k-65k) at the start. Early training gets single high tiles. Later training gets specific configurations (e.g., 16k+8k, or 32k+16k+8k). Saves thousands of moves, letting agents experience endgame scenarios faster.

- Endgame-only environments (env-level): Dedicated training that only practices endgame because a single mistake ends the game. Always starts with high-value tiles pre-placed (e.g., 32k, 16k, 8k, 4k).

Policy architecture: 3.7M parameters with LSTM memory. It changed rarely.

- Encoder: Three FC layers with GELU (1024 -> 512 -> 512).

- Memory: LSTM layer (512x512) for long-horizon planning.

- The LSTM is critical for 2048’s 45k+ move games (when reaching the 65k tile).

The Road Ahead: Shooting for 132k

Reaching the 65,536 tile requires 40k+ moves with precise sequencing. The strategy you start at move 20k affects whether you succeed at move 25k.

So how can we shoot for 132k? On top of more training steps, these two directions seem promising:

- Deeper networks: The 1000 Layer Networks research shows that extreme depth can unlock new goal-reaching capabilities in RL.

- Automated curriculum: The Go-Explore algorithm could automatically discover the “stepping stones” to higher tiles more efficiently than manual scaffolding.

Tetris: When Bugs Become Features

Tetris is forgiving early on but becomes impossible as speed increases. My journey here led to an unexpected insight about curriculum learning.

I started with hyperparameter sweeps and increased network width from 128 to 256. Better hyperparameters alone made the agent much better. The agent kept playing endlessly, which was boring to watch. So I made the game harder:

- Garbage lines: Random filled rows at the bottom.

- Progression: Quicker ramps in drop speed and garbage frequency.

The breakthrough came from a bug.

A bug caused the one-hot encoding for the next two pieces to persist between steps. Over time, the observation array would fill with 1s, essentially becoming noise.

When I fixed this bug, the agents did well in the beginning but couldn’t handle when gaps started to appear. With the bug, the agents performed much better overall, though early-stage play was somewhat off. Why? Early exposure to chaos made the agents robust. When they encountered genuinely difficult late-game situations (fast drops, lots of garbage), they’d already learned to handle messy, unpredictable states. The bug had accidentally implemented curriculum learning through randomization.

So I implemented two curriculum approaches:

- External: Injecting random garbage lines during early training.

- Internal: Mimicking the bug by adding observation noise that decays over time.

Both create early-game “hard states” that teach robustness. I don’t know which is better; sometimes external works, other times internal. So I left both versions in the code.

Here is the training log. You can play it in your browser here.

Overall, Tetris is easier because you’re mostly reacting to the current piece and next few pieces, not planning 40k+ moves ahead like 2048.

Lessons: What Actually Mattered

- Speed giveth: Training on a single RTX 4090 worked because the environment was fast enough to run hundreds of hyperparameter sweeps. Fast simulation transforms RL from “YOLO and pray” into systematic search.

- Hyperparameters matter: They can easily double performance without other changes.

- Nail obs and reward first: A bigger network won’t fix poor observation or reward design. Scale the network last.

- Curriculum makes superhuman: Agents cannot learn what they haven’t experienced. Curriculum learning lets agents experience critical states that would take too long (or be impossible) to reach naturally.

- Systematic grind > Clever one-shot: Progress came from disciplined grind, sleepless nights, with little inspiration sprinkled in between.

- Bug luck: Don’t let a lucky bug slip by; it might teach you something good.

Try It Yourself

Watch the agents play: 2048, Tetris

Code: PufferLib

Training commands: After installing PufferLib, run puffer train puffer_g2048 or puffer train puffer_tetris

These results show that a single person with a gaming desktop can achieve much more than you’d think. Also, if you’re considering scaling up, think again. Having many CPUs and GPUs to throw at a problem is nice, but it’s much more fun squeezing the last drop of perf out (but yeah, I also saw Sutton’s The Bitter Lesson).