Authored by Brendon Fallon & Lynn Xu via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

For decades, cholesterol screening has focused on a familiar set of numbers—LDL (“bad” cholesterol), HDL (“good” cholesterol), and triglycerides. When these values fall within the “normal” range, many people are reassured that their heart risk is low.

However, according to leading preventive cardiologist Dr. Seth J. Baum, that reassurance can sometimes be misleading.

In a recent episode of “Vital Signs,” Baum explained that a largely inherited cholesterol-related particle—lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a)—can quietly raise the risk of heart attack, stroke, and aortic valve disease, even in people whose standard cholesterol tests look perfectly fine.

“Lp(a) explains a lot of heart disease we used to call bad luck,” Baum said. “It’s not bad luck—it’s biology we weren’t measuring.”

What Is Lipoprotein(a)?

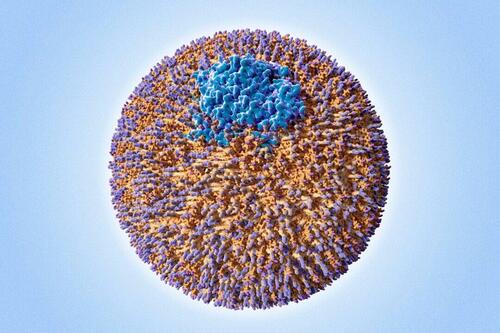

Lipoprotein(a) is structurally similar to LDL cholesterol, but with an added protein called apolipoprotein(a). This extra component makes the particle particularly harmful because it promotes plaque buildup, inflammation, and abnormal clot formation within blood vessels.

Unlike LDL cholesterol—which is strongly influenced by diet, exercise, and medications—Lp(a) levels are determined primarily by genetics. They remain relatively stable throughout life and are largely unaffected by lifestyle changes.

Because of this, Baum and other preventive cardiologists often refer to Lp(a) as “genetic cholesterol.” It is inherited, invisible on routine lipid panels, and easily overlooked—yet clinically powerful.

How Common Is High Lp(a)?

Elevated Lp(a) is not rare. Large population studies and expert consensus estimate that more than 20 percent of people worldwide—roughly one in five adults—have Lp(a) levels high enough to increase cardiovascular risk. In the United States, this translates to approximately 64 million adults.

That prevalence rivals or exceeds that of many conditions routinely screened for in primary care. Yet most Americans have never had their Lp(a) measured.

Baum said that this gap in testing helps explain why some people develop heart disease at young ages or despite healthy lifestyles.

“I see patients who’ve been told for years their cholesterol is fine,” he said. “Then they have a heart attack at 45. When we finally check Lp(a), the story suddenly makes sense.”

Normal Cholesterol Doesn’t Always Mean Low Risk

One of Baum’s central messages is that cholesterol numbers must be interpreted in context, not in isolation.

Lp(a) acts as a risk amplifier. When it is elevated, other risk factors—such as mildly high LDL, borderline blood pressure, insulin resistance, or smoking—become more dangerous in combination. The artery is not only accumulating plaque faster, but plaque is also more inflamed and more prone to forming clots. Two people with identical LDL levels may have very different outcomes, depending on their Lp(a) levels.

This helps explain why traditional risk calculators sometimes fail, particularly in people with heart attacks or strokes at unusually young ages, strong family histories of cardiovascular disease, or heart disease that seems disproportionate to lifestyle.

In Baum’s view, overlooking Lp(a) in these situations represents a major blind spot in prevention.

The Test Most People Never Get–But Probably Should

Because Lp(a) rarely changes over time, testing is usually only needed once. The result can meaningfully alter how clinicians assess risk and guide prevention—even before Lp(a)-specific drugs become widely available.

Lp(a) results may be reported in different units, but many experts consider levels greater than or equal to 50 mg/dL (or approximately 100 to 125 nmol/L, depending on the assay) to be clinically significant.

Importantly, high Lp(a) is not a diagnosis. It does not mean a heart attack is inevitable. Rather, it signals that cardiovascular prevention should be more proactive and individualized. “Lp(a) doesn’t act alone—it stacks on top of everything else,” Baum said.

He describes Lp(a) as a “triple threat” because it promotes plaque formation, enhances blood clotting, and intensifies vascular inflammation. “Inflammation is clearly involved in plaque progression and heart attacks,” he noted, explaining why Lp(a) carries risk beyond LDL alone.

Despite this, Baum estimates that only about 1 percent of the population has ever been tested for Lp(a). “The reason most doctors cite for not testing is that we don’t yet have an approved therapy to lower it,” he said. “But that’s not a good reason not to know the risk.”

Plaque builds silently over decades. “In the vast majority of patients with high cholesterol or Lp(a), you don’t see anything on physical exam,” he said. “You usually don’t see anything until there’s a heart attack or stroke.”

A Practical Prevention Plan

A common misconception is that high Lp(a) leaves patients powerless. Baum strongly disagrees. “You can’t change your genes, but you can absolutely change how aggressively you manage everything else.”

Lower LDL More Than Average

When Lp(a) is elevated, Baum often targets lower LDL or apoB levels than standard recommendations. Even modest LDL elevations can be more harmful in the presence of high Lp(a), so tolerance for “borderline” values is reduced.

Treat Risk Factors as Additive

Rather than viewing blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and lifestyle habits separately, Baum said that they compound one another.

With high Lp(a):

- Mild hypertension matters more

- Smoking carries greater danger

- Poor sleep, inactivity, and metabolic dysfunction become more consequential

This cumulative perspective explains why clinicians may recommend earlier or more intensive intervention—even when no single risk factor appears extreme.

Use Imaging to Clarify Risk

Baum highlighted the value of coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring, a specialized CT scan that detects and measures calcified plaque in the coronary arteries—the arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle.

Unlike blood tests, which estimate risk indirectly, CAC scoring provides direct visual evidence of atherosclerosis. A higher calcium score reflects a greater plaque burden and a higher likelihood of future cardiovascular events.

In people with elevated Lp(a) but otherwise uncertain risk, CAC can help determine whether genetic risk has already translated into physical disease. A positive CAC score suggests that plaque has begun to form, strengthening the case for earlier and more aggressive prevention. A CAC score of zero indicates no detectable calcified plaque at the time of testing and may allow for a more individualized approach, particularly in younger patients.

CAC does not replace blood testing, Baum said, but adds clarity when lab results and clinical history leave risk uncertain—helping tailor prevention to the person, not just the numbers.

Screen Your Family

Because Lp(a) is inherited, Baum strongly encourages cascade screening—testing close relatives once an elevated level is identified. “The youngest person in the family is often the one who shows up first with an event.”

Family-wide screening—including siblings, parents, and children—can improve early detection and prevention.

Advanced Options and Emerging Therapies

For patients with prior cardiovascular events and very high Lp(a), lipoprotein apheresis may be an option in specialized centers.

Lipoprotein apheresis is a blood-filtering procedure that removes atherogenic lipoproteins—particles that promote artery-clogging plaque. These include LDL cholesterol and Lp(a), the structural protein found on particles most responsible for atherosclerosis. It is currently available at about 50 centers in the United States.

“We can literally remove these particles from the blood every two weeks, and hopefully reduce the risk of another event.”

Several Lp(a)-lowering drugs are now in late-stage clinical trials, some showing 80 percent to 90 percent reductions in Lp(a) levels. Baum expects FDA-approved therapies in the coming years, though he cautions that outcome data—not just lab results—will determine their ultimate value.

Baum’s Top 3 Recommendations

After decades of treating patients with both typical and unexplained heart disease, Baum said that effective prevention begins not with fear, but with awareness, engagement, and early action. His top recommendations are practical steps anyone can take to better understand—and reduce—their cardiovascular risk.

1. Be Your Own Advocate

“The most important aspect of cardiovascular prevention is taking it seriously and advocating for yourself.”

That starts with asking questions, understanding your family history, and requesting appropriate testing—especially when something doesn’t add up. Knowing whether Lp(a) or apoB is elevated can reveal risks that routine cholesterol panels miss.

2. Work With a Knowledgeable Physician

Even with a trusted doctor, it’s reasonable to have a proactive conversation about cardiovascular risk. Baum encourages patients to ask about Lp(a) and apoB testing, particularly if there is a family history of early heart disease or unexplained events.

Patients with similar LDL levels may require very different treatment intensity depending on their genetic risk, imaging results, and overall clinical picture.

3. Talk to Your Family

When genetic risk is involved, one test result can help protect an entire family. Because Lp(a) is inherited, identifying it in one person often leads to early detection—and prevention—in siblings, parents, or children.

Lp(a) helps explain why heart disease sometimes strikes people who seem to be doing everything right. It is common, inherited, and invisible on standard tests—but no longer ignorable.

A single blood test can uncover hidden risk and reshape prevention for decades.

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” Baum said. “Lp(a) is one of the most important things we’ve been missing.”

Loading recommendations...