Remember files?

You write a document, hit save, and the file is on your computer. It’s yours. You can inspect it, you can send it to a friend, and you can open it with other apps.

Files come from the paradigm of personal computing.

This post, however, isn’t about personal computing. What I want to talk about is social computing—apps like Instagram, Reddit, Tumblr, GitHub, and TikTok.

What do files have to do with social computing?

Historically, not a lot—until recently.

But first, a shoutout to files.

Files, as originally invented, were not meant to live inside the apps.

Since files represent your creations, they should live somewhere that you control. Apps create and read your files on your behalf, but files don’t belong to the apps.

Files belong to you—the person using those apps.

Apps (and their developers) may not own your files, but they do need to be able to read and write them. To do that reliably, apps need your files to be structured. This is why app developers, as part of creating apps, may invent and evolve file formats.

A file format is like a language. An app might “speak” several formats. A single format can be understood by many apps. Apps and formats are many-to-many. File formats let different apps work together without knowing about each other.

Consider this .svg:

SVG is an open specification. This means that different developers agree on how to read and write SVG. I created this SVG file in Excalidraw, but I could have used Adobe Illustrator or Inkscape instead. Your browser already knew how to display this SVG. It didn’t need to hit any Excalidraw APIs or to ask permissions from Excalidraw to display this SVG. It doesn’t matter which app has created this SVG.

The file format is the API.

Of course, not all file formats are open or documented.

Some file formats are application-specific or even proprietary like .doc. And yet, although .doc was undocumented, it didn’t stop motivated developers from reverse-engineering it and creating more software that reads and writes .doc:

Another win for the files paradigm.

The files paradigm captures a real-world intuition about tools: what we make with a tool does not belong to the tool. A manuscript doesn’t stay inside the typewriter, a photo doesn’t stay inside the camera, and a song doesn’t stay in the microphone.

Our memories, our thoughts, our designs should outlive the software we used to create them. An app-agnostic storage (the filesystem) enforces this separation.

A file has many lives.

You may create a file in one app, but someone else can read it using another app. You may switch the apps you use, or use them together. You may convert a file from one format to another. As long as two apps correctly “speak” the same file format, they can work in tandem even if their developers hate each others’ guts.

And if the app sucks?

Someone could always create “the next app” for the files you already have:

Apps may come and go, but files stay—at least, as long as our apps think in files.

When you think of social apps—Instagram, Reddit, Tumblr, GitHub, TikTok—you probably don’t think about files. Files are for personal computing only, right?

A Tumblr post isn’t a file.

An Instagram follow isn’t a file.

A Hacker News upvote isn’t a file.

But what if they behaved as files—at least, in all the important ways? Suppose you had a folder that contained all of the things ever POSTed by your online persona:

It would include everything you’ve created across different social apps—your posts, likes, scrobbles, recipes, etc. Maybe we can call it your “everything folder”.

Of course, closed apps like Instagram aren’t built this way. But imagine they were. In that world, a “Tumblr post” or an “Instagram follow” are social file formats:

- You posting on Tumblr would create a “Tumblr post” file in your folder.

- You following on Instagram would put an “Instagram follow” file into your folder.

- You upvoting on Hacker News would add an “HN upvote” file to your folder.

Note this folder is not some kind of an archive. It’s where your data actually lives:

Files are the source of truth—the apps would reflect whatever’s in your folder.

Any writes to your folder would be synced to the interested apps. For example, deleting an “Instagram follow” file would work just as well as unfollowing through the app. Crossposting to three Tumblr communities could be done by creating three “Tumblr post” files. Under the hood, each app manages files in your folder.

In this paradigm, apps are reactive to files. Every app’s database mostly becomes derived data—an app-specific cached materialized view of everybody’s folders.

This might sound very hypothetical, but it’s not. What I’ve described so far is the premise behind the AT protocol. It works in production at scale. Bluesky, Leaflet, Tangled, Semble, and Wisp are some of the new open social apps built this way.

It doesn’t feel different to use those apps. But by lifting user data out of the apps, we force the same separation as we’ve had in personal computing: apps don’t trap what you make with them. Someone can always make a new app for old data:

Like before, app developers evolve their file formats. However, they can’t gatekeep who reads and writes files in those formats. Which apps to use is up to you.

Together, everyone’s folders form something like a distributed social filesystem:

I’ve previously written about the AT protocol in Open Social, looking at its model from a web-centric perspective. But I think that looking at it from the filesystem perspective is just as intriguing, so I invite you to take a tour of how it works.

A personal filesystem starts with a file.

What does a social filesystem start with?

A Record

Here is a typical social media post:

How would you represent it as a file?

It’s natural to consider JSON as a format. After all, that’s what you’d return if you were building an API. So let’s fully describe this post as a piece of JSON:

{

author: {

avatar: 'https://example.com/dril.jpg',

displayName: 'wint',

handle: 'dril'

},

text: 'no',

createdAt: '2008-09-15T17:25:00.000Z',

replyCount: 819,

repostCount: 56137,

likeCount: 125381

}However, if we want to store this post as a file, it doesn’t make sense to embed the author information there. After all, if the author later changes their display name or avatar, we wouldn’t want to go through their every post and change them there.

So let’s assume their avatar and name live somewhere else—perhaps, in another file. We could leave author: 'dril' in the JSON but this is unnecessary too. Since this file lives inside the creator’s folder—it’s their post, after all—we can always figure out the author based on whose folder we’re currently looking at.

Let’s remove the author field completely:

{

text: 'no',

createdAt: '2008-09-15T17:25:00.000Z',

replyCount: 819,

repostCount: 56137,

likeCount: 125381

}This seems like a good way to describe this post:

But wait, no, this is still wrong.

You see, replyCount, repostCount, and likeCount are not really something that the post’s author has created. These values are derived from the data created by other people—their replies, their reposts, their likes. The app that displays this post will have to keep track of those somehow, but they aren’t this user’s data.

So really, we’re left with just this:

{

text: 'no',

createdAt: '2008-09-15T17:25:00.000Z'

}That’s our post as a file!

Notice how it took some trimming to identify which parts of the data actually belong in this file. This is something that you have to be intentional about when creating apps with the AT protocol. My mental model for this is to think about the POST request. When the user created this thing, what data did they send? That’s likely close to what we’ll want to store. That’s the stuff the user has just created.

Our social filesystem will be structured more rigidly than a traditional filesystem. For example, it will only consist of JSON files. To make this more explicit, we’ll start introducing our new terminology. We’ll call this kind of file a record.

Record Keys

Now we need to give our record a name. There are no natural names for posts. Could we use sequential numbers? Our names need only be unique within a folder:

posts/

├── 1.json

├── 2.json

└── 3.jsonOne downside is that we’d have to keep track of the latest one so there’s a risk of collisions when creating many files from different devices at the same time.

Instead, let’s use timestamps with some per-clock randomness mixed in:

posts/

├── 1221499500000000-c5.json

├── 1221499500000000-k3.json # clock id helps avoid global collisions

└── 1221499500000001-k3.json # artificial +1 avoids local collisionsThis is nicer because these can be generated locally and will almost never collide.

We’ll use these names in URLs so let’s encode them more compactly. We’ll pick our encoding carefully so that sorting alphabetically goes in the chronological order:

posts/

├── 34qye3wows2c5.json

├── 34qye3wows2k3.json

└── 34qye3wows3k3.jsonNow ls -r gives us a reverse chronological timeline of posts! That’s neat. Also, since we’re sticking with JSON as our lingua franca, we don’t need file extensions.

posts/

├── 34qye3wows2c5

├── 34qye3wows2k3

└── 34qye3wows3k3Not all records accumulate over time. For example, you can write many posts, but you only have one copy of profile information—your avatar and display name. For “singleton” records, it makes sense to use a predefined name, like me or self:

posts/

├── 34qye3wows2c5

├── 34qye3wows2k3

└── 34qye3wows3k3

profiles/

└── selfBy the way, let’s save this profile record to profiles/self:

{

avatar: 'https://example.com/dril.jpg",

displayName: 'wint'

}Note how, taken together, posts/34qye3wows2c5 and profiles/self let us reconstruct more of the UI we started with, although some parts are still missing:

Before we fill them in, though, we need to make our system sturdier.

Lexicons

This was the shape of our post record:

{

text: 'no',

createdAt: '2008-09-15T17:25:00.000Z'

}And this was the shape of our profile record:

{

avatar: 'https://example.com/dril.jpg",

displayName: 'wint'

}Since these are stored as files, it’s important for the format not to drift.

Let’s write some type definitions:

type Post = {

text: string,

createdAt: string

};

type Profile = {

avatar?: string,

displayName?: string

};TypeScript seems convenient for this but it isn’t sufficient. For example, we can’t express constraints like “the text string should have at most 300 Unicode graphemes”, or “the createdAt string should be formatted as datetime”.

We need a richer way to define social file formats.

We might shop around for existing options (RDF? JSON Schema?) but if nothing quite fits, we might as well design our own schema language explicitly geared towards the needs of our social filesystem. This is what our Post looks like:

{

// ...

"defs": {

"main": {

"type": "record",

"key": "tid",

"record": {

"type": "object",

"required": ["text", "createdAt"],

"properties": {

"text": { "type": "string", "maxGraphemes": 300 },

"createdAt": { "type": "string", "format": "datetime" }

}

}

}

}

}We’ll call this the Post lexicon because it’s like a language our app wants to speak.

My first reaction was also “ouch” but it helped to think that conceptually it’s this:

type Post = {

@maxGraphemes(300) text: string,

createdAt: datetime

};I used to yearn for a better syntax but I’ve actually come around to hesitantly appreciate the JSON. It being trivial to parse makes it super easy to build tooling around it (more on that in the end). And of course, we can make bindings turning these into type definitions and validation code for any programming language.

Collections

Our social filesystem looks like this so far:

posts/

├── 34qye3wows2c5

├── 34qye3wows2k3

└── 34qye3wows3k3

profiles/

└── selfThe posts/ folder has records that satisfy the Post lexicon, and the profiles/ folder contains records (a single record, really) that satisfy the Profile lexicon.

This can be made to work well for a single app. But here’s a problem. What if there’s another app with its own notion of “posts” and “profiles”?

Recall, each user has an “everything folder” with data from every app:

Different apps will likely disagree on what the format of a “post” is! For example, a microblog post might have a 300 character limit, but a proper blog post might not.

Can we get the apps to agree with each other?

We could try to put every app developer in the same room until they all agree on a perfect lexicon for a post. That would be an interesting use of everyone’s time.

For some use cases, like cross-site syndication, a standard-ish jointly governed lexicon makes sense. For other cases, you really want the app to be in charge. It’s actually good that different products can disagree about what a post is! Different products, different vibes. We’d want to support that, not to fight it.

Really, we’ve been asking the wrong question. We don’t need every app developer to agree on what a post is; we just need to let anyone “define” their own post.

We could try namespacing types of records by the app name:

twitter/

├── posts/

│ ├── 34qye3wows2c5

│ ├── 34qye3wows2k3

│ └── 34qye3wows3k3

└── profiles/

└── self

tumblr/

├── posts/

│ ├── 34qye3wows4c5

│ └── 34qye3wows5k3

└── profiles/

└── selfBut then, app names can also clash. Luckily, we already have a way to avoid conflicts—domain names. A domain name is unique and implies ownership.

Why don’t we take some inspiration from Java?

com.twitter.post/

├── 34qye3wows2c5

├── 34qye3wows2k3

└── 34qye3wows3k3

com.twitter.profile/

└── self

com.tumblr.post/

├── 34qye3wows4c5

└── 34qye3wows5k3

com.tumblr.profile/

└── selfThis gives us collections.

A collection is a folder with records of a certain lexicon type. Twitter’s lexicon for posts might differ from Tumblr’s, and that’s fine—they’re in separate collections. The collection is always named like <whoever.designs.the.lexicon>.<name>.

For example, you could imagine these collection names:

com.instagram.followfor Instagram followsfm.last.scrobblefor Last.fm scrobblesio.letterboxd.reviewfor Letterboxd reviews

You could also imagine these slightly whackier collection names:

com.ycombinator.news.vote(subdomains are ok)co.wint.shitpost(personal domains work too)org.schema.recipe(a shared standard someday?)fm.last.scrobble_v2(breaking changes = new lexicon, just like file formats)

It’s like having a dedicated folder for every file extension.

To see some real lexicon names, check out UFOs and Lexicon Garden.

There Is No Lexicon Police

If you’re an application author, you might be thinking:

Who enforces that the records match their lexicons? If any app can (with the user’s explicit consent) write into any other app’s collection, how do we not end up with a lot of invalid data? What if some other app puts junk into “my” collection?

The answer is that records could be junk, but it still works out anyway.

It helps to draw a parallel to file extensions. Nothing stops someone from renaming cat.jpg to cat.pdf. A PDF reader would just refuse to open it.

Lexicon validation works the same way. The com.tumblr in com.tumblr.post signals who designed the lexicon, but the records themselves could have been created by any app at all. This is why apps always treat records as untrusted input, similar to POST request bodies. When you generate type definitions from a lexicon, you also get a function that will do the validation for you. If some record passes the check, great—you get a typed object. If not, fine, ignore that record.

So, validate on read, just like files.

Some care is required when evolving lexicons. From the moment some lexicon is used in the wild, you should never change which records it would consider valid. For example, you can add new optional fields, but you can’t change whether some field is optional. This ensures that the new code can still read old records and that the old code will be able to read any new records. There’s a linter to check for this. (For breaking changes, make a new lexicon, as you would do with a file format.)

Although this is not required, you can publish your lexicons for documentation and distribution. It’s like publishing type definitions. There’s no separate registry for those; you just put them into a com.atproto.lexicon.schema collection of some account, and then prove the lexicon’s domain is owned by you. For example, if I wanted to publish an io.overreacted.comment lexicon, I could place it here:

app.bsky.feed.post/

├── 3mclfkzg4uc2k

├── 3mcleqsh7cc2k

└── 3mclejvlp5c2k

com.atproto.lexicon.schema

└── io.overreacted.commentThen I’d need to do some DNS setup to prove overreacted.io is mine. This would make my lexicon show up in pdsls, Lexicon Garden, and other tools.

Links

Let’s circle back to our post.

We’ve already decided that the profile should live in the com.twitter.profile collection, and the post itself should live in the com.twitter.post collection:

But what about the likes?

Actually, what is a like?

A like is something that the user creates, so it makes sense for each like to be a record. A like record doesn’t convey any data other than which post is being liked:

type Post = {

text: string,

createdAt: string

};

// ...

type Like = {

subject: Post

};In TypeScript, we expressed this as a reference to the Post type. Since lexicons are JSON files with globally unique names, here’s how we’ll say this in lexicon:

{

"lexicon": 1,

"id": "com.twitter.like",

"defs": {

"main": {

"type": "record",

"key": "tid",

"record": {

"type": "object",

"required": ["subject"],

"properties": {

"subject": { "type": "ref", "ref": "com.twitter.post" }

}

}

}

}

}We’re saying: a Like is an object with a subject field that refers to some Post.

However, “refers” is doing a lot of work here. What does a Like record actually look like? How do you actually refer from inside of one JSON file to another JSON file?

{

subject: "???"

}We could try to refer to the Post record by its path in our “everything folder”:

{

subject: "com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}But this only uniquely identifies it within a single user’s “everything folder”. Recall that each user has their own, completely isolated folders with all of their stuff:

We need to find some way to refer to the users themselves:

{

subject: "???????????????????????????????/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}How do we do it?

Identity

This is a difficult problem.

So far, we’ve been building up a kind of a filesystem for social apps. But the “social” part requires linking between users. We need a reliable way to refer to some user. The challenge is that we’re building a distributed filesystem where the “everything folders” of different users may be hosted on different computers, by different companies, communities or organizations, or be self-hosted.

What’s more, we don’t want anyone to be locked into their current hosting. The user should be able to change who hosts their “everything folder” at any point, and without breaking any existing links to their files. The main tension is that we want to preserve users’ ability to change their hosting, but we don’t want that to break any links. Additionally, we want to make sure that, although the system is distributed, we’re confident that each piece of data has not been tampered with.

For now, you can forget all about records, collections, and folders. We’ll focus on a single problem: links. More concretely, we need a design for permanent links that allow swappable hosting. If we don’t make this work, everything else falls apart.

Attempt 1: Host as Identity

Suppose dril’s content is hosted by some-cool-free-hosting.com. The most intuitive way to link to his content is to use a normal HTTP link to his hosting:

{

subject: "https://some-cool-free-hosting.com/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}This works, but then if dril wants to change his hosting, he’d break every link. So this is not a solution—it’s the exact problem that we’re trying to solve. We want the links to point at “wherever dril’s stuff will be”, not “where dril’s stuff is right now”.

We need some kind of an indirection.

Attempt 2: Handle as Identity

We could give dril some persistent identifier like @dril and use that in links:

{

subject: "@dril/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}We could then run a registry that stores a JSON document like this for each user:

{

// ...

"service": [{

// ...

"serviceEndpoint": "https://some-cool-free-hosting.com"

}]

}The idea is that this document tells us how to find @dril’s actual hosting.

We’d also need to provide some way for dril to update this document.

Some version of this could work but it seems unfortunate to invent our own global namespace when one already exists on the internet. Let’s try a twist on this idea.

Attempt 3: Domain as Identity

There’s already a global namespace anyone can participate in: DNS. If dril owns wint.co, maybe we could let him use that domain as his persistent identity:

{

subject: "@wint.co/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}This doesn’t mean that the actual content is hosted at wint.co; it just means that wint.co hosts the JSON document that says where the content currently is. For example, maybe the convention is to serve that document as /document.json. Again, the document points us at the hosting. Obviously, dril can update his doc.

This is somewhat elegant but in practice the tradeoff isn’t great. Losing domains is pretty common, and most people wouldn’t want that to brick their accounts.

Attempt 4: Hash as Identity

The last two attempts share a flaw: they tie you to the same handle forever.

Whether it’s a handle like @dril or a domain handle like @wint.co, we want people to be able to change their handles at any time without breaking links.

Sounds familiar? We also want the same for hosting. So let’s keep the “domain handles” idea but store the current handle in JSON alongside the current hosting:

{

// ...

"alsoKnownAs": ["@wint.co"],

// ...

"service": [{

// ...

"serviceEndpoint": "https://some-cool-free-hosting.com"

}]

}This JSON is turning into sort of a calling card for your identity. “Call me @wint.co, my stuff is at https://some-cool-free-hosting.com.”

Now we need somewhere to host this document, and some way for you to edit it.

Let’s revisit the “centralized registry” from approach #2. One problem with it was using handles as permanent identifiers. Also, centralized is bad, but why is it bad? It’s bad for many reasons, but usually it’s the risk of abuse of power or a single point of failure. Maybe we can, if not remove, then reduce some of those risks. For example, it would be nice if could make the registry’s output self-verifiable.

Let’s see if we can use mathematics to help with this.

When you create an account, we’ll generate a private and a public key. We then create a piece of JSON with your initial handle, hosting, and public key. We sign this “create account” operation with your private key. Then we hash the signed operation. That gives us a string of gibberish like 6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo.

The registry will store your operation under that hash. That hash becomes the permanent identifier for your account. We’ll use it in links to refer to you:

{

subject: "6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}To resolve a link like this, we ask the registry for the document belonging to 6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo. It returns current your hosting, handle, and public key. Then we fetch com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5 from your hosting.

Okay, but how do you update your handle or your hosting in this registry?

To update, you create a new operation with a prev field set to the hash of your previous operation. You sign it and send it to the registry. The registry validates the signature, appends the operation to your log, and updates the document.

To prove that it doesn’t forge the served documents, the registry exposes an endpoint that lists past operations for an identifier. To verify an operation, you check that its signature is valid and that its prev field matches the hash of the operation before it. This lets you verify the entire chain of updates down to the first operation. The hash of the first operation is the identifier, so you can verify that too. At that point, you know that every change was signed with the user’s key.

(More on the trust model in the PLC specification.)

With this approach, the registry is still centralized but it can’t forge anyone’s documents without the risk of that being detected. To further reduce the need to trust the registry, we make its entire operation log auditable. The registry would hold no private data and be entirely open source. Ideally, it would eventually be spun it out into an independent legal entity so that long-term it can be like ICANN.

Since most people wouldn’t want to do key management, it’s assumed the hosting would hold the keys on behalf of the user. The registry includes a way to register an overriding rotational key, which is helpful in case the hosting itself goes rogue. (I wish for a way to set this up with a good UX; most people don’t have this on.)

Finally, since the handle is now determined by the document held in the registry, we’ll need to add some way for a domain to signal that it agrees with being some identifier’s handle. This could be done via DNS, HTTPS, or a mix of both.

Phew! This is not perfect but it gets us surprisingly far.

Attempt 5: DID as Identity

From the end user perspective, attempt #4 (hash as identity) is the most friendly. It doesn’t use domains for identity (only as handles), so losing a domain is fine.

However, some find relying on a third-party registry, no matter how transparent, untenable. So it would be nice to support approach #3 (domain as identity) too.

We’ll use a flexible identifier standard called DID (decentralized identifier) which is essentially a way to namespace multiple unrelated identification methods:

did:web:wint.coand such — domain-based (attempt #3)did:plc:6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjoand such — registry-based (attempt #4)- This also leaves us a room to add other methods in the future, like

did:bla:...

This makes our Like record look like this:

{

subject: "at://did:plc:6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}This is going to be its final form. We write at:// here to remind ourselves that this isn’t an HTTP link, and that you need to follow the resolution procedure (get the document, get the hosting, then get the record) to actually get the result.

Now you can forget everything we just discussed and remember four things:

- A DID is a string identifier that represents an account.

- An account’s DID never changes.

- Every DID points at a document with the current hosting, handle, and public key.

- A handle needs to be verified in the other direction (the domain must agree).

The mental model is that there’s a function like this:

async function resolveDID(did) {

// ...

return { hosting, handle, publicKey };

}You give it a DID, and it returns where to find their stuff, their bidirectionally verified current handle, and their public key. You’ll want a 'use cache' on it.

Let’s now finish our social filesystem.

at:// URI

With a DID, we can finally construct a path that identifies every particular record:

at://did:plc:6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5

└─────────── who ──────────────┘ └─ collection ─┘ └── record ─┘An at:// URI is a link to a record that survives hosting and handle changes.

The mental model here is that you can always resolve it to a record:

async function fetchRecord(atURI) {

const { did, collection, rkey } = parseATUri(atURI);

const { hosting } = await resolveDID(did);

const params = `repo=${did}&collection=${collection}&rkey=${rkey}`;

return fetch(`${hosting}/xrpc/com.atproto.repo.getRecord?${params}`);

}If the hosting is down, it would temporarily not resolve, but if the user puts it up anywhere and points their DID there, it will start resolving again. The user can also delete the record, which would remove it from the user’s “everything folder”.

Another way to think about at:// URI is that it is as a unique identifier of every record in our filesystem, so it can serve as a key in a database or a cache.

Hyperlinks for JSON

With links, we can finally represent relationships between records.

Let’s look at dril’s post again:

Where do the 125 thousand likes come from?

These are just 125 thousand com.twitter.like records in different people’s “everything folders” that each link to dril’s com.twitter.post record:

Where do the 56K reposts come from? Similarly, this means that there are 56K com.twitter.repost records across our social filesystem linking to this post:

What about the replies?

A reply is just a post that has a parent post. In TypeScript, we’d write it like this:

type Post = {

text: string,

createdAt: string

parent?: Post

};In lexicon, we’d write it like this:

// ...

"text": { "type": "string", "maxGraphemes": 300 },

"createdAt": { "type": "string", "format": "datetime" },

"parent": { "type": "ref", "ref": "com.twitter.post" }

// ...This says: the parent field is a reference to another com.twitter.post record.

Every reply to dril’s post will have dril’s post as their parent:

{

"text": "yes",

"createdAt": "2008-09-15T18:02:00.000Z",

"parent": "at://did:plc:6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5"

}So, to get the reply count, we just need to count every such post:

We’ve now explained how every piece of the original UI can be derived from files:

- The display name and avi come from dril’s

com.twitter.profile/self. - The tweet text and date come from dril’s

com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5. - The like count is aggregated from everyone’s

com.twitter.likes. - The repost count is aggregated from everyone’s

com.twitter.reposts. - The reply count is aggregated from everyone’s

com.twitter.posts.

The last finishing touch is the handle. Unfortunately, @dril can no longer work as a handle since we’ve chosen to use domains as handles. As a consolation, dril would be able to use @wint.co across every future social app if he would like to.

A Repository

It’s time to give our “everything folder” a proper name. We’ll call it a repository. A repository is identified by a DID. It contains collections, which contain records:

did:plc:fpruhuo22xkm5o7ttr2ktxdo/

├── com.twitter.like/

│ └── ...

├── com.twitter.post/

│ └── ...

├── fm.last.scrobble/

│ ├── 3ld5nsp8q2w9j

│ ├── 3ld5ntq9r3x0k

│ └── ...

└── com.ycombinator.news.vote/

├── 3ld6our0s4y1l

└── ...Each repository is a user’s little piece of the social filesystem. A repository can be hosted anywhere—a free provider, a paid service, or your own server. You can move your repository as many times as you’d like without breaking links.

One challenge with building a social filesystem in practice is that apps need to be able to compute derived data (e.g. like counts) with no extra overhead. Of course, it would be completely impractical to look for every com.twitter.like record in every repo referencing a specific post when trying to serve the UI for that post.

This is why, in addition to treating a repository as a filesystem—you can list and read stuff—you can treat it as a stream, subscribing to it by a WebSocket. This lets anyone build a local app-specific cache with just the derived data that app needs. Over the stream, you receive each commit as an event, along with the tree delta.

For example, a Hacker News backend could listen to creates/updates/deletes of com.ycombinator.news.* records in every known repository and save those records locally for fast querying. It could also track derived data like vote_count.

Subscribing to every known repository from every app is inconvenient. It is nicer to use dedicated services called relays which retransmit all events. However, this raises the issue of trust: how do you know whether someone else’s relay is lying?

To solve this, let’s make the repository data self-certifying. We can structure the repository as a hash tree. Each write is a signed commit containing the new root hash. This makes it possible to verify records as they come in against their original authors’ public keys. As long as you subscribe to a relay that retransmits its proofs, you can check every proof to know the records are authentic.

Verifying authenticity of records does not require storing their content, which means that relays can act as simple retransmitters and are affordable to run.

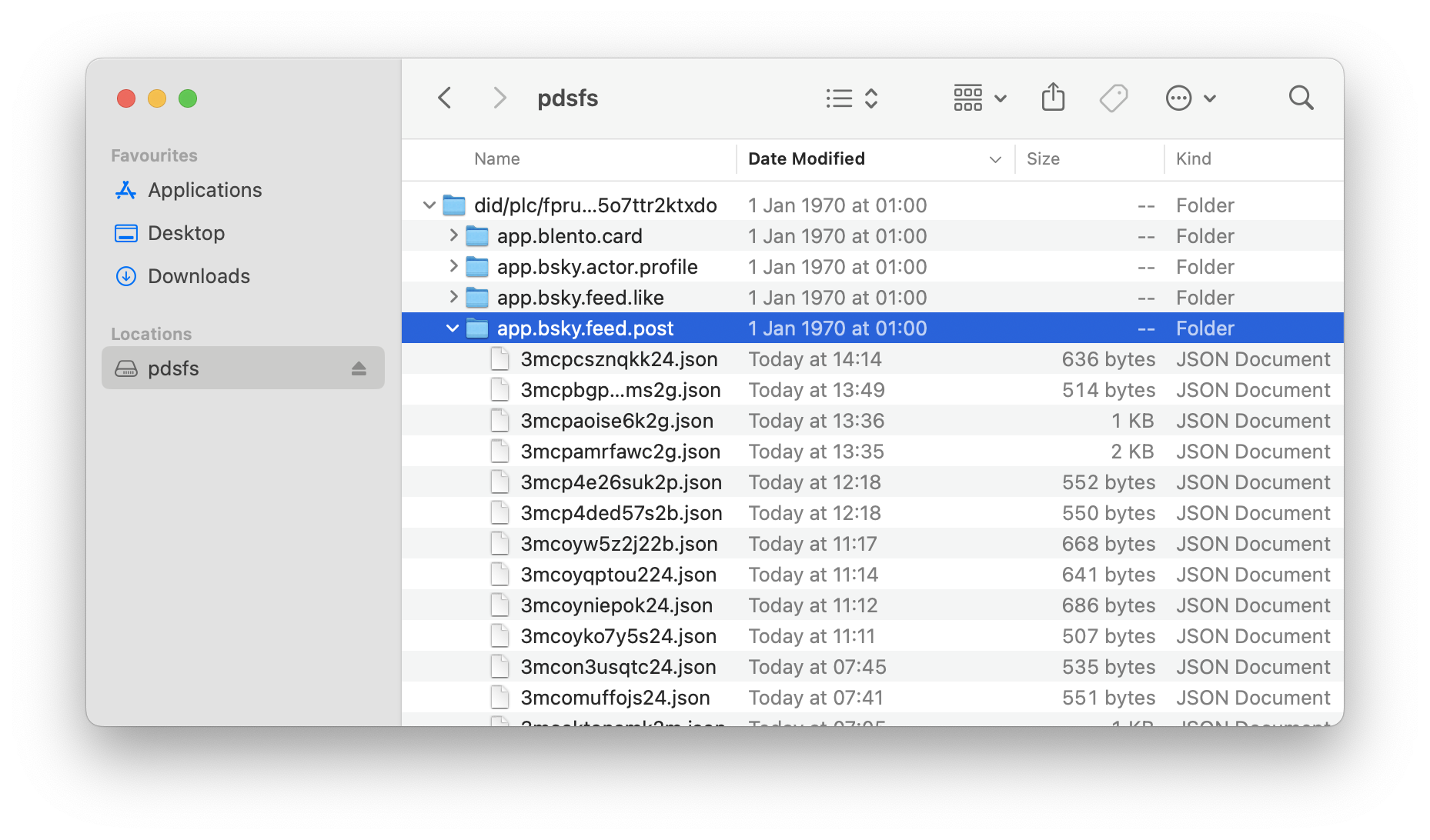

Open pdsls.

If you want to explore the Atmosphere (at://-mosphere, get it?), pdsls is the best starting point. Given a DID or a handle, it shows a list of collections and their records. It’s really like an old school file manager, except for the social stuff.

Here’s at://danabra.mov if you want some random place to start. Notice that you understand 80% of what’s going on there—Collections, Identity, Records, etc. Feel free to branch in. Records link to other links, etc. There is almost no aggregation there so it feels a little “ungrounded” (e.g. there is no thread view like in Bluesky) but there are some interesting navigational features like Backlinks.

Watch me walk around the Atmosphere for a bit:

(Yeah, what was that lexicon?! I didn’t expect to run into this while recording.)

Anyway, my favorite demo is this.

Watch me create a Bluesky post by creating a record via pdsls:

This works with any AT app, there’s nothing special about Bluesky. In fact, every AT app that cares to listen to events about the Bluesky Post lexicon knows that this post has been created. Apps live downstream from everybody’s records.

I could even mount pdsfs and see all my stuff update locally:

For my personal learning, a month ago I’ve made a little app called Sidetrail (it’s open source) which lets you create step-by-step walkthroughs and “walk” those.

Here you can see I’m deleting an app.sidetrail.walk record in pdsls, and the corresponding walk disappears from my Sidetrail “walking” tab:

I know exactly why it works, it’s not supposed to surprise me, but it does! My repo really is the source of truth. My data lives in the Atmosphere, and apps “react” to it.

It’s weird!!!

Here is the code of my ingester:

export async function handleEvent(db: IngesterDb, evt: JetstreamEvent): Promise<void> {

if (evt.kind === "account") {

await handleAccountEvent(db, evt.account);

return;

}

if (evt.kind === "identity") return;

if (evt.kind !== "commit") return;

const { commit } = evt;

const { collection, rkey } = commit;

if (!COLLECTIONS.includes(collection)) return;

const [accountStatus] = await db

.select({ active: accounts.active })

.from(accounts)

.where(eq(accounts.did, evt.did))

.limit(1);

if (accountStatus && !accountStatus.active) {

return;

}

const uri = `at://${evt.did}/${collection}/${rkey}`;

if (commit.operation === "delete") {

switch (collection) {

case "app.sidetrail.trail":

await deleteTrail(db, uri);

break;

case "app.sidetrail.walk":

await deleteWalk(db, uri);

break;

case "app.sidetrail.completion":

await deleteCompletion(db, uri);

break;

}

return;

}

const record = commit.record as Record<string, unknown>;

await ensureAccount(db, evt.did);

switch (collection) {

case "app.sidetrail.trail":

await upsertTrail(

db,

uri,

commit.cid,

evt.did,

rkey,

record,

(record.createdAt as string) || new Date().toISOString(),

);

break;

case "app.sidetrail.walk": {

const trailRef = record.trail as { uri: string } | undefined;

const trailUri = trailRef?.uri || "";

await upsertWalk(

db,

uri,

commit.cid,

evt.did,

rkey,

trailUri,

record,

(record.createdAt as string) || new Date().toISOString(),

);

break;

}

case "app.sidetrail.completion": {

const trailRef = record.trail as { uri: string } | undefined;

const trailUri = trailRef?.uri || "";

await upsertCompletion(

db,

uri,

commit.cid,

evt.did,

rkey,

trailUri,

record,

(record.createdAt as string) || new Date().toISOString(),

);

break;

}

}

}This syncs everyone’s repo changes to my database so I have a snapshot that’s easy to query. I’m sure I could write this more clearly, but conceptually, it’s like I’m re-rendering my database. It’s like I called a setState “above” the internet, and now the new props flow down from files into apps, and my DB reacts to them.

I could delete those tables in production, and then use Tap to backfill my database from scratch. I’m just caching a slice of the global data. And everyone building AT apps also needs to cache some slices. Maybe different slices, but they overlap. So pooling resources becomes more useful. Or at least there’s more shared tooling.

I have another example I really like.

Here is a teal.fm Relay demo made by @chadmiller.com that show the list of everyone’s recently played tracks, as well as some of the overall stats:

Now, you can see it says “678,850 scrobbles” at the top of the screen. You might think people have been scrobbling their plays to the teal.fm API for a while.

Well, not really.

The teal.fm API doesn’t actually exist. It’s not a thing. Moreover, the teal.fm product doesn’t actually exist either. I mean, I think it’s in development (this is a hobby project!), but at the time of writing, https://teal.fm/ is only a landing page.

But this doesn’t matter!

All you need to start scrobbling is to put records of the fm.teal.alpha.feed.play lexicon into your repo.

The lexicon isn’t published as a record (yet?) but it’s easy to find on GitHub. So anyone can build a scrobbler that writes these. I’m using one of those scrobblers.

Here’s my scrobble showing up:

(It’s a bit slow but I think the delay is on the Spotify/scrobbler integration side.)

To be clear, the person who made this demo doesn’t work on teal.fm either. It’s not an “official” demo or anything, and it’s also not using the “teal.fm database” or “teal.fm API” or anything like it. It just indexes fm.teal.alpha.feed.plays.

I wonder if people are playing anything right now:

Speaking of this demo, it uses the new lex-gql package which is another of @chadtmiller.com’s experiments. You give it some lexicons, and it lets you run GraphQL on your backfilled snapshot of the relevant parts of the social filesystem.

If you have the world’s JSON, why not run joins over products?

fragment TrackItem_play on FmTealAlphaFeedPlay {

trackName

playedTime

artists {

artistName

}

releaseName

releaseMbId

actorHandle

musicServiceBaseDomain

appBskyActorProfileByDid {

displayName

avatar {

url(preset: "avatar")

}

}

}

Here’s one last example that I thought was interesting.

For months, I’ve been complaining about the Bluesky’s default Discover feed which, frankly, doesn’t work all that great for me. Then I heard people saying good things about @spacecowboy17.bsky.social’s For You algorithm.

I’ve been giving it a try, and I really like it!

I ended up switching to it completely. It reminds me of the Twitter algo in 2017—the swings are a bit hard but it finds the stuff I wouldn’t want to miss. It’s also much more responsive to “Show Less”. Its core principle seems pretty simple.

How does a custom feed like this work? Well, a Bluesky feed is just an endpoint that returns a list of at:// URIs. That’s the contract. You know how this works.

[

{ post: 'at://did:example:1234/app.bsky.feed.post/1' },

{ post: 'at://did:example:1234/app.bsky.feed.post/2' },

{ post: 'at://did:example:1234/app.bsky.feed.post/3' }

]Could there be feeds of things other than posts? Sure.

Funnily enough, @spacecowboy17.bsky.social used to run For You from a home computer. He posts a lot of interesting stuff, like A/B tests of feed changes. Also, here’s a For You debugger for my account. “Switch perspectives” is cool.

There was a tweet a few weeks ago clowning on Bluesky for being so bad at algorithms that users have to install a third-party feed to get a good experience.

I agree with @dame.is that this shows something important: Bluesky is a place where that can happen. Why? In the Atmosphere, third party is first party. We’re all building projections of the same data. It’s a feature that someone can do it better.

An everything app tries to do everything.

An everything ecosystem lets everything get done.