In my previous post on Homoiconic Python, I explored McCarthy’s Lisp, a language where code and data are the same thing. But there’s another path to expressive power, one that emerged in parallel.

At the 1956 Dartmouth conference, John McCarthy encountered Newell and Simon’s list-processing language IPL. He liked the idea of lists but hated the language itself, so he spent the next two years building Lisp at MIT. That same year, Kenneth Iverson was teaching mathematics at Harvard and growing frustrated with the inadequacy of conventional notation for expressing algorithms. He began inventing his own, publishing it in 1962 as A Programming Language, the book that gave APL its name.

APL looked like nothing else. Iverson designed a new alphabet, like Egyptian hieroglyphics, each symbol a complete idea:

APL is very expressive. Here is the complete implementation of Conway's Game of Life in APL:

life ← {⊃1 ⍵ ∨.∧ 3 4 = +/ +⌿ ¯1 0 1 ∘.⊖ ¯1 0 1 ⌽¨ ⊂⍵}And just like Lisp, APL had one data structure: the array. Lisp had the list.

This shared minimalism is the first hint of a deeper, ancestral bond.

Lisp was born at MIT; APL at Harvard. Lisp processes lists; APL processes matrices. Lisp inherits from Church’s lambda calculus; APL from Curry’s combinators. Lisp was designed for machines to do symbolic reasoning; APL was designed for humans to communicate mathematical ideas. One prioritizes semantic elegance, the other syntactic density.

APL and LISP are very similar languages—both manipulate a complex data structure and the functional structure of the languages has been ideally chosen for convenient manipulation of these structures. Proposals have been made to combine them by embedding one within the other.

In 1979, Alan Perlis (the first recipient of the Turing Award) chaired a panel asking: ”APL and LISP—should they be combined, and if so how?” The panel debated embedding one within the other, or generalizing both into something superior. No conclusion was reached. That same year, Iverson received his own Turing Award and delivered his famous lecture: Notation as a Tool of Thought.

You’ve probably used Iverson’s ideas without knowing it. John Baker calls NumPy an ”Iverson ghost”, APL’s array programming reborn in Python’s syntax. Broadcasting, vectorization, reduction along axes-these aren’t NumPy inventions. They’re Iverson’s ideas from the 1960s, wrapped in `np.` prefixes and spelled out in English.

PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX-the entire deep learning stack speaks Iverson’s dialect with extra syllables. `np.arange(10)` is `!10`. `np.cumsum(x)` is `+\x`. `x[::-1]` is `|x`. Same concepts, more typing.

Arthur Whitney, Iverson’s protégé, saw both languages clearly. On kparc.com (his personal website) he listed K’s lineage simply as “lisp and apl,” linking to Iverson’s Turing paper and Perlis’s lyrical programming. In a 2009 interview, he explained: ”I much preferred implementing and coding in LISP, but once I was dealing with big data sets... APL just seemed to have the better vocabulary.” He understood their complementary strengths: ”What I liked was the original LISP, which had car, cdr, cons, and cond, but that was too little. Common LISP was way too big, but a stripped-down version of APL was in the middle with about 50 operations.”

Whitney first encountered APL at age 11, when Iverson (a friend of his father’s) demonstrated interactive programming on a terminal in 1969. But it wasn’t until 1980, working alongside Iverson at I.P. Sharp in Toronto, that he began using it seriously. Through the ‘80s he explored broadly, implementing his own object-oriented languages, various Lisps, and Prolog. In 1988 he joined Morgan Stanley and built trading systems using his own APL dialect, which became A+.

In 1989, Whitney visited Iverson at Kiln Farm. Iverson and Roger Hui were working on a new APL dialect-one that would use ASCII instead of special glyphs. Over one afternoon, Whitney wrote the now famous incunabulum. A one page interpreter in C.

That’s Arthur’s style: C that looks like APL. Macros turn C into a higher-order language; by the time he writes the interpreter, he’s writing APL in C. It looks alien at first glance, then you see it. This is code golfing at its earliest (popular among APL hackers long before Perl coined the term).

Roger Hui studied that page for a week, then wrote the first line of what would become J. J shipped in 1990, the first ASCII APL. But Whitney wasn’t done.

In 1992, Whitney created K. Where J modernized APL’s syntax, K transformed its semantics. On kparc.com, he laid out exactly what K inherited from each parent:

The parallels are striking. Both functional. Both dynamic. Both built on atoms and lists with maps between them. Both with REPLs and lexical scope. The syntax differs (s-expressions versus m-expressions) but the bones are the same.

K marked a major departure from APL tradition and towards LISP influence, since it discarded APL’s multidimensional array model in favor of nested lists.

The Lisp features crept in gradually. Lambda and conditionals appeared in the 1970s. Higher-order operators-map and reduce-arrived in 1979, the same year Perlis posed his question. ASCII came with J in 1989. But the decisive break was 1992: K abandoned APL’s multidimensional arrays for nested lists-Lisp’s data structure.

APL & Lisp, after four decades of parallel evolution, finally merged as k.

This is what K looks like (using the 90 lines python implemntation from next section). Factorial:

*/1+!5

120Average:

(+/x)%#x:!100

49.5Primes under 50:

&2=+/0=(a)mod/a:1+!50

[2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47] 🤯Golden ratio via continued fraction:

0{1+1%x}/1

1.618033988749895Fibonacci:

5{|+\x}\1,2

[[1, 2], [3, 1], [4, 3], [7, 4], [11, 7], [18, 11]]Pi via Madhava series:

4*+/(-*\-_a%a:1+!n)*1%1+2*!n:1000000

3.1415916535897743Euler’s number:

*/x*1+1%#x:_x%x:1+!1000000

2.7182804690959363Square root of 2 via Newton:

1+100{1%2+x}/1

1.4142135623730951How do you build K in Python?

The data structure is already there, Python lists can represent Lisp lists (as I showed in my previous post). The symbols? K already uses ASCII. What’s missing is what makes APL special: everything is vectorized. We need scalar extension. Then parser/eval, this is where we lay the syntactic sugar, the notation if you will, of APL on top of Lisp. Lisp is semantics, APL is syntax.

Enter monad and dyad. Two higher-order functions that vectorize *any* Python function:

atom = lambda x: isinstance(x, (int, float, str))

monad = lambda f: lambda x: f(x) if atom(x) else list(map(monad(f), x))

dyad = lambda f: (lambda x, y: f(x, y) if atom(x) and atom(y)

else list(map(lambda yi: dyad(f)(x, yi), y)) if atom(x)

else list(map(lambda xi: dyad(f)(xi, y), x)) if atom(y)

else list(map(lambda xi, yi: dyad(f)(xi, yi), x, y)))Monad lifts a unary (one argument, i.e. f(x)) function. Dyad lifts a binary (two arguments, i.e. f(x,y)) one. They recurse into structure until they find atoms, then apply. This is scalar extension, the heart of array programming.

Watch what happens:

>>> import math

>>> sqrt = monad(math.sqrt)

>>> sqrt(4)

2.0

>>> sqrt([4, 9, 16])

[2.0, 3.0, 4.0]

>>> sqrt([[4, 9], [16, 25]])

[[2.0, 3.0], [4.0, 5.0]]

>>> add = dyad(lambda x, y: x + y)

>>> add(1, 2)

3

>>> add(10, [1, 2, 3])

[11, 12, 13]

>>> add([1, 2], [10, 20])

[11, 22]Any function. Any depth. No loops. No NumPy. Just two higher-order functions.

dyad function works exactly like this:

atom + atom → apply directly

atom + list → extend the atom (scalar extension)

list + atom → extend the atom (scalar extension)

list + list → pairwise

monad function makes functions pervasive, it penetrates into nested structures recursively.

These two functions are what inspired me to build the whole thing.

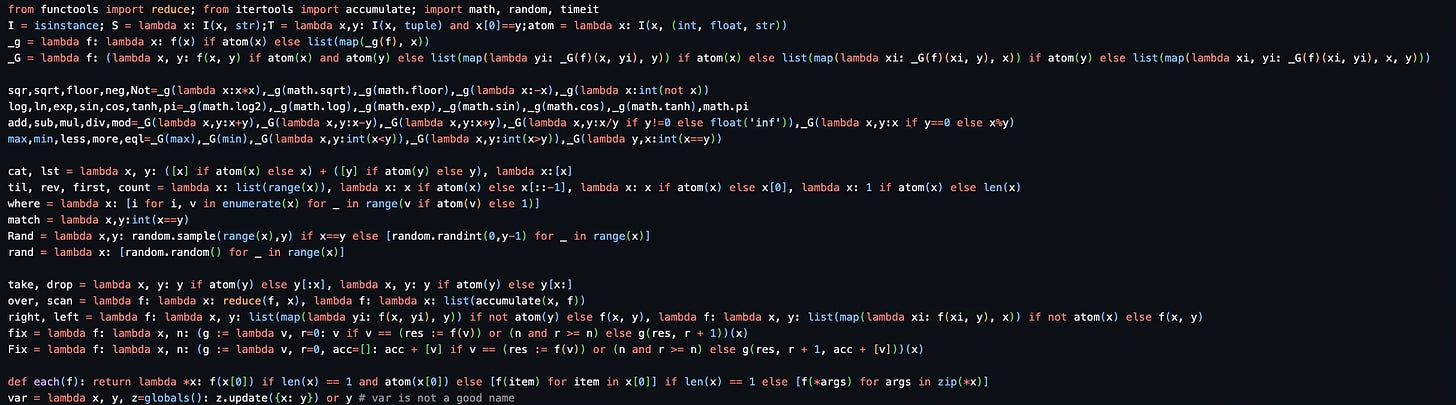

Armed with scalar extension and a feel for K’s semantics, I wanted to see how far terseness could go. I wanted to implement the whole thing in under 100 lines of Python, honoring the tradition of my predecessors. Here it is:

Lisp: code is data. Empahsis on semantics.

APL: notation is thought. Empahsis on syntax.

K: both.

Less is more.

For more details, check out k.py on GitHub.