I have a credit card with HSBC: you know, the bank with virtue-signalling multiculturalism in their ads.

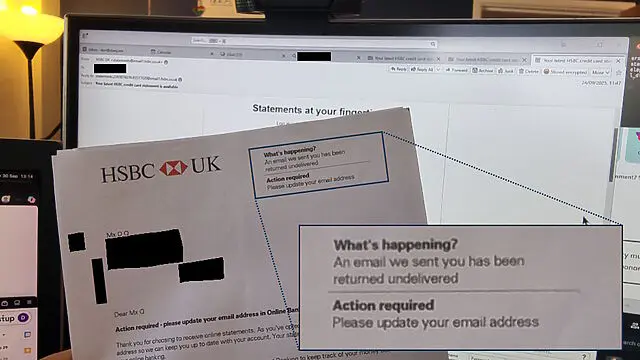

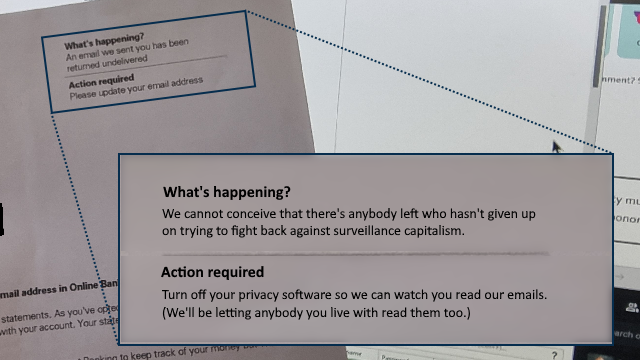

Not long ago I received a letter from them telling me that emails to me were being “returned undelivered” and they needed me to update the email address on my account.

“What’s happening?”

I logged into my account, per the instructions in the letter, and discovered my correct email address already right there, much to my… lack of surprise.

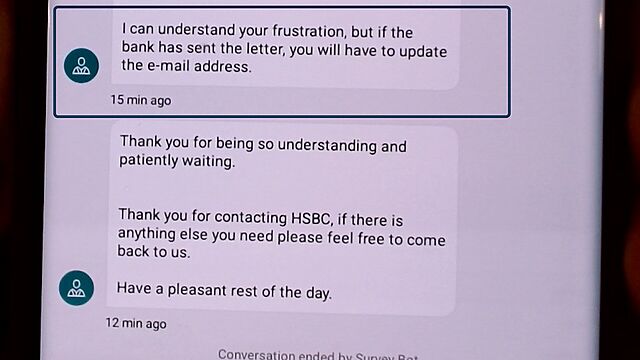

So I kicked off a live chat via their app, with an agent called Ankitha. Over the course of a drawn-out hour-long conversation, they repeatedly told to tell me how to update my email address (which was never my question). Eventually, when they understood that my email address was already correct, then they concluded the call, saying (emphasis mine):

I can understand your frustration, but if the bank has sent the letter, you will have to update the e-mail address.

This is the point at which a normal person would probably just change the email address in their online banking to a “spare” email address.

But aside from the fact that I’d rather not, by this point I’d caught the scent of a deeper underlying issue. After all, didn’t I have a conversation a little like this one but with a different bank, about four years ago?

So I called Customer Services directly, who told me that if my email address is already correct then I can ignore their letter.

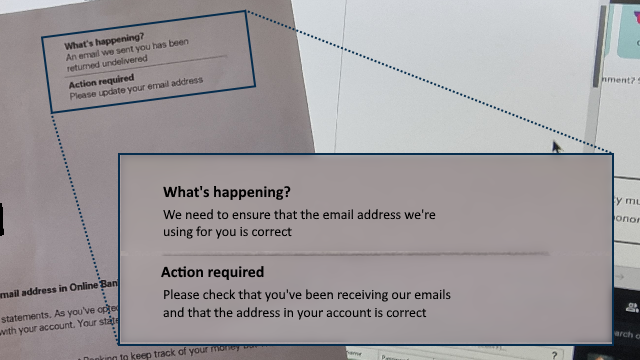

I suggested that perhaps their letter template might need updating so it doesn’t say “action required” if action is not required. Or that perhaps what they mean to say is “action required: check your email address is correct”.

So anyway, apparently everything’s fine… although I reserved final judgement until I’d seen that they were still sending me emails!

“Action required”

I think I can place a solid guess about what went wrong here. But it makes me feel like we’re living in the Darkest Timeline.

I dissected HSBC’s latest email to me: it was of the “your latest statement is available” variety. Deep within the email, down at the bottom, is this code:

<img src="http://www.email1.hsbc.co.uk:8080/Tm90IHRoZSByZWFsIEhTQkMgcGF5bG9hZA==" width="1" height="1" alt=""> <img src="http://www.email1.hsbc.co.uk:8080/QWxzbyBub3QgcmVhbCBIU0JDIHBheWxvYWQ=" width="1" height="1" alt="">

What you’re seeing are two tracking pixels: tiny 1×1 pixel images, usually transparent or white-on-white to make them even-more invisible, used to surreptitiously track when somebody reads an email. When you open an email from HSBC – potentially every time you open an email from them – your email client connects to those web addresses to get the necessary images. The code at the end of each identifies the email they were contained within, which in turn can be linked back to the recipient.

You know how invasive a read-receipt feels? Tracking pixels are like those… but turned up to eleven. While a read-receipt only says “the recipient read this email” (usually only after the recipient gives consent for it to do so), a tracking pixel can often track when and how often you refer to an email.

If I re-read a year-old email from HSBC, they’re saying that they want to know about it.

But it gets worse. Because HSBC are using http://, rather than https:// URLs for their tracking pixels, they’re also saying that every time you read an email

from them, they’d like everybody on the same network as you to be able to know that you did so, too. If you’re at my house, on my WiFi, and you open an email from HSBC, not

only might HSBC know about it, but I might know about it too.

An easily-avoidable security failure there, HSBC… which isn’t the kind of thing one hopes to hear about a bank!

But… tracking pixels don’t actually work. At least, they doesn’t work on me. Like many privacy-conscious individuals, my devices are configured to block tracking pixels (and a variety of other instruments of surveillance capitalism) right out of the gate.

This means that even though I do read most of the non-spam email that lands in my Inbox, the sender doesn’t get to know that I did so unless I choose to tell them. This is the way that email was designed to work, and is the only way that a sender can be confident that it will work.

But we’re in the Darkest Timeline. Tracking pixels have become so endemic that HSBC have clearly come to the opinion that if they can’t track when I open their emails, I must not be receiving their emails. So they wrote me a letter to tell me that my emails have been “returned undelivered” (which seems to be an outright lie).

Surveillance capitalism has become so ubiquitous that it’s become transparent. Transparent like the invisible spies at the bottom of your bank’s emails.

So in summary, with only a little speculation:

- Surveillance capitalism became widespread enough that HSBC came to assume that tracking pixels have bulletproof reliability.

-

HSBC started using tracking pixels them to check whether emails are being received (even though that’s not what they do when they are reliable, which

they’re not).

- (Oh, and their tracking pixels are badly-implemented, if they worked they’d “leak” data to other people on my network.)

- Eventually, HSBC assumed their tracking was bulletproof. Because HSBC couldn’t track how often, when, and where I was reading their emails… they posted me a letter to tell me I needed to change my email address.

What do I think HSBC should do?

Instead of sending me a misleading letter about undelivered emails, perhaps a better approach for HSBC could be:

- At an absolute minimum, stop using unencrypted connections for tracking pixels. I do not want to open a bank email on a cafe’s public WiFi and have everybody in the cafe potentially know who I bank with… and that I just opened an email from them! I certainly don’t want attackers injecting content into the bottom of legitimate emails.

- Stop assuming that if somebody blocks your attempts to spy on them via your emails, it means they’re not getting your emails. It doesn’t mean that. It’s never meant that. There are all kinds of reasons that your tracking pixels might not work, and they’re not even all privacy-related reasons!

- Or, better yet: just stop trying to surveil your customers’ email habits in the first place? You already sit on a wealth of personal and financial information which you can, and probably do, data-mine for your own benefit. Can you at least try to pay lip service to your own published principles on the ethical use of data and, if I may quote them, “use only that data which is appropriate for the purpose” and “embed privacy considerations into design and approval processes”.

- If you need to check that an email address is valid, do that, not an unreliable proxy for it. Instead of this letter, you could have sent an email that said “We need to check that you’re receiving our emails. Please click this link to confirm that you are.” This not only achieves informed consent for your tracking, but it can be more-secure too because you can authenticate the user during the process.

Also, to quote your own principles once more: when you make a mistake like assuming your spying is a flawless way to detect the validity of email addresses, perhaps you should “be transparent with our customers and other stakeholders about how we use their data”.

Wouldn’t that be better than writing to a customer to say that their emails are being returned undelivered (when they’re not)… and then having your staff tell them that having received such an email they have no choice but to change the email address they use (which is then disputed by your other staff)?

</rant>