TL;DR: Mandarin pronunciation has been hard for me, so I took ~300 hours of transcribed speech and trained a small CTC model to grade my pronunciation. You can try it here.

In my previous post about Langseed, I introduced a platform for defining words using only vocabulary I had already mastered. My vocabulary has grown since then, but unfortunately, people still struggle to understand what I'm saying.

Part of the problem is tones. They're fairly foreign to me, and I'm bad at hearing my own mistakes, which is deeply frustrating when you don’t have a teacher.

First attempt: pitch visualisation

My initial plan was to build a pitch visualiser: split incoming audio into small chunks, run an FFT, extract the dominant pitch over time, and map it using an energy-based heuristic, loosely inspired by Praat.

But this approach quickly became brittle. There were endless special cases: background noise, coarticulation, speaker variation, voicing transitions, and so on.

And if there’s one thing we’ve learned over the last decade, it’s the bitter lesson: when you have enough data and compute, learned representations usually beat carefully hand-tuned systems.

So instead, I decided to build a deep learning–based Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Training (CAPT) system that could run entirely on-device. There are already commercial APIs that do this, but hey, where’s the fun in that?

Architecture

I treated this as a specialised Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) task. Instead of just transcribing text, the model needs to be pedantic about how something was said.

I settled on a Conformer encoder trained with CTC (Connectionist Temporal Classification) loss.

Why Conformer?

Speech is weird: you need to catch both local and global patterns:

-

Local interactions

The difference between a retroflex zh and an alveolar z happens in a split second. CNNs are excellent at capturing these short-range spectral features. -

Global interactions

Mandarin tones are relative (a "high" pitch for me might be low for a child) and context-dependent (tone sandhi). Transformers excel at modeling this longer-range context.

Conformers combine both: convolution for local detail, attention for global structure.

Why CTC?

Most modern ASR models (e.g. Whisper) are sequence-to-sequence: they turn audio into the most likely text. The downside is they'll happily auto-correct you.

That’s a feature for transcription, but it’s a bug for language learning. If my tone is wrong, I don’t want the model to guess what I meant. I want it to tell me what I actually said.

CTC works differently. It outputs a probability distribution for every frame of audio (roughly every 40 ms). To handle alignment, it introduces a special <blank> token.

If the audio is "hello", the raw output might look like:

h h h <blank> e e <blank> l l l l <blank> l l o o o

Collapsing repeats and removing blanks gives hello. This forces the model has to deal with what I actually said, frame by frame.

Forced alignment: knowing when you said it

CTC tells us what was said, but not exactly when.

For a 3-second clip, the model might output a matrix with ~150 time steps (columns), each containing probabilities over all tokens (rows). Most of that matrix is just <blank>.

If the user reads "Nǐ hǎo" (ni3, hao3), we expect two regions of high probability: one for ni3, one for hao3.

We need to find a single, optimal path through this matrix that:

- Starts at the beginning

- Ends at the end

- Passes through

ni3→hao3in order - Maximises total probability

This is exactly what the Viterbi algorithm computes, using dynamic programming.

Tokenisation: Pinyin + tone as first-class tokens

Most Mandarin ASR systems output Hanzi. That hides pronunciation errors, because the writing system encodes meaning rather than pronunciation.

Instead, I created a token for every Pinyin syllable + tone:

zhong1is one tokenzhong4is a completely different token

If I say the wrong tone, the model explicitly predicts the wrong token ID.

I also normalised the neutral tone by forcing it to be tone 5 (ma5). This resulted in a vocabulary of 1,254 tokens, plus <unk> and <blank>.

Training

I combined the AISHELL-1 and Primewords datasets (~300 hours total), augmented by SpecAugment (time/frequency masking). On 4× NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090s, training took about 8 hours. Instead of obsessing over loss, I mostly focused on these metrics:

- TER (Token Error Rate): overall accuracy.

- Tone Accuracy: accuracy over tones 1-5.

- Confusion Groups: errors between difficult initial pairs like zh/ch/sh vs z/c/s.

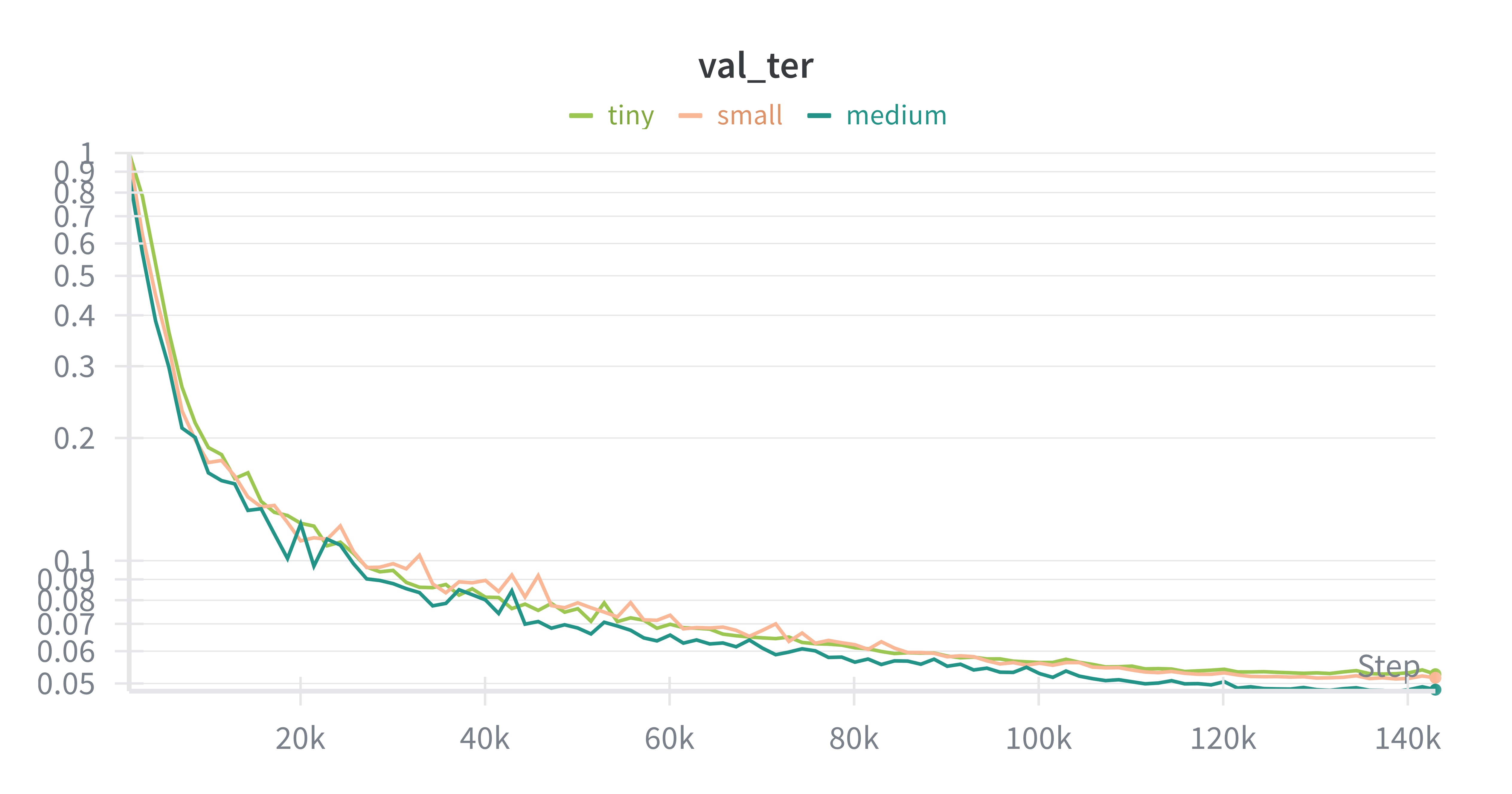

Honey, I shrank the model

I started with a "medium" model (~75M parameters). It worked well, but I wanted something that could run in a browser or on a phone without killing the battery.

So I kept shrinking it, and I was honestly surprised by how little accuracy I lost:

| # Parameters | TER | Tone accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| 75M | 4.83% | 98.47% |

| 35M | 5.16% | 98.36% |

| 9M | 5.27% | 98.29% |

The 9M-parameter model was barely worse. This strongly suggests the task is data-bound, not compute-bound.

The FP32 model was ~37 MB. After INT8 quantisation, it shrank to ~11 MB with a negligible accuracy drop (+0.0003 TER). Small enough to load instantly via onnxruntime-web.

Alignment bug: silence ruins everything

To highlight mistakes, we need forced alignment. But I hit a nasty bug with leading silence.

I recorded myself saying "我喜欢…" and paused for a second before speaking. The model confidently told me my first syllable was wrong. Confidence score: 0.0.

Why?

The alignment assigned the silent frames to wo3. When I averaged probabilities over that span, the overwhelming <blank> probability completely drowned out wo3.

The fix

I decoupled UI spans (what gets highlighted) from scoring frames (what contributes to confidence).

We simply ignore frames where the model is confident it’s seeing silence:

def _filter_nonblank_frames(span_logp: torch.Tensor, blank_id: int = 0, thr: float = 0.7):

"""

Only keep frames where the probability of <blank> is below a threshold.

If we filter everything (total silence), we fall back to scoring the whole span.

"""

p_blank = span_logp[:, blank_id].exp()

keep = p_blank < thr

if keep.any():

return span_logp[keep]

return span_logp # Fallback

This single change moved my confidence score for the first syllable from 0.0 → 0.99.

Conclusion

I can already feel my pronunciation improving while beta testing this. It’s strict and unforgiving, exactly what I needed.

Native speakers, interestingly, complained that they had to over-enunciate to get marked correct. That’s likely a domain-shift issue: AISHELL is mostly read speech, while casual speech is faster and more slurred. Kids do poorly too: their pitch is higher, and they're basically absent from the training data. Adding conversational datasets like Common Voice feels like the obvious next step.

You can try the live demo here. It runs entirely in your browser. The download is ~13MB, still smaller than most websites today.