By Javier Medina ( X / LinkedIn)

TL;DR

A toy projector taught the same lesson we keep seeing in serious systems.

Business models create rules that need security properties; and questionable shortcuts tend to replace these properties when time, money and knowledge are scarce.

In this case, media protection was a reversible single byte XOR wrapper and the NFC cartridge acted as merely like an index selector. With simple home tools, we could model the whole ecosystem in less than 1 hour. But what matters, beyond the toy itself, is what this small case teaches us.

Responsible research note

This is a consumer toy with no reachable security contact and we found no evidence that the issue exposes PII, impact on third-party services or introduces direct physical safety risks. We’re publishing this write-up to highlight the underlying architectural failure mode.

To avoid enabling misuse, this post doesn’t focus on the vendor and intentionally omits some elements necessary for direct reproduction of the detected vulnerabilities. We have deliberately avoided publishing scripts that remove the content protection or generate playable custom content. Likewise, we will not provide the original media files or the full structure/layout of the NFC tags.

The intent is to document recurring design patterns rather than target a specific product.

1# Are you seriously talking about a €10 projector?

We hesitated to publish this here.

On the surface, it’s a toy story. The reason to share it is the patterns behind it.

Small systems and big systems fail in similar ways and often for a mix of the same reasons: deadlines, ridiculous budget, missing security review, lack of knowledge or designs that rely on looks protected.

So, yes, this started with a cheap projector made for children’s stories.

The bundle is really simple. A projector, a microSD card with the media files and a plastic circular cartridge that the device reads using contactless tech.

You put the cartridge and the projector plays one story… and you can continue doing so as long as you buy more cartridges that cost the same as you paid for the projector. It’s a well-established business model, backed by a large publishing group.

But to be honest, all this thoughtful reflection came later, because the beginning of this story starts my children asking an embarrassing question.

Can we watch something else on it?

What won’t a father do for his children?

Hands on

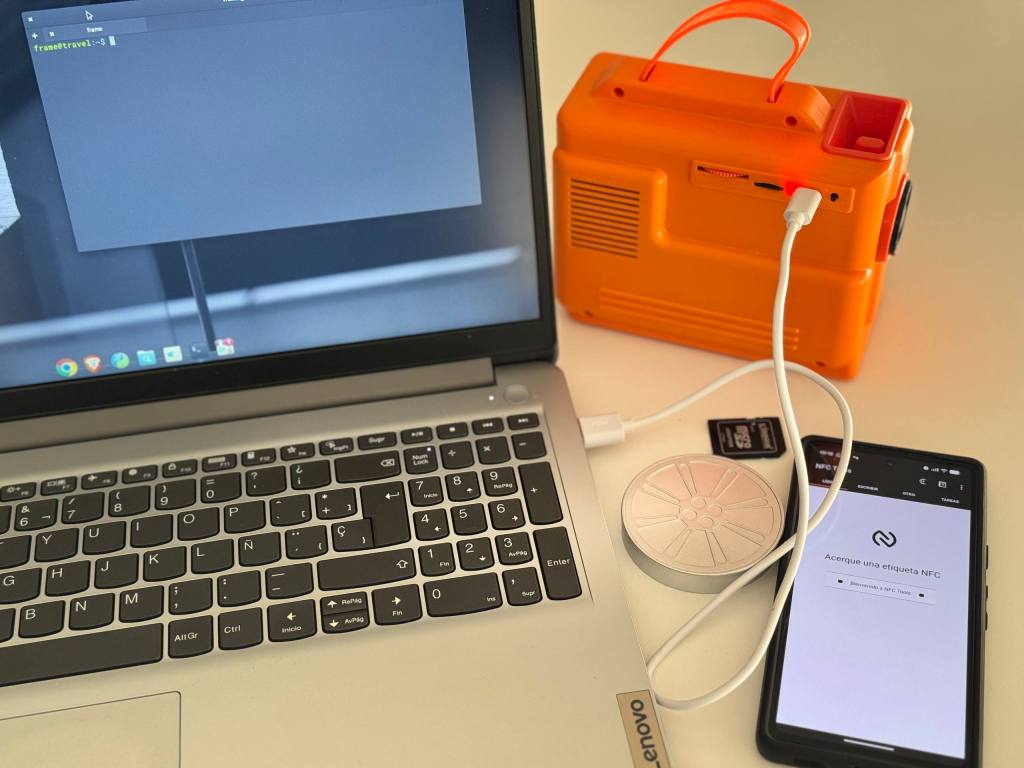

We kept the setup as basic as the question that started it:

- The microSD card from the bundle

- The plastic cartridge with contactless tech

- A home laptop

- A microSD to SD adapter

- An Android phone with an NFC utility app

That was enough.

We assumed a curious user with physical access to the SD card, to the cartridge and equipped with basic tools. We did not attempt invasive hardware work, firmware extraction or media parser exploitation.

This matters because effort level is part of the story. When a closed ecosystem can be understood with tools as these, in a short session of less than 60 minutes, the security controls are clearly decorative.

2# Findings in 60 minutes

Although it was a toy and, honestly, there was no doubt that it would break relatively easily, we approached the exercise as if a customer had arrived with six-figure hardware and told us to break it.

Phase 1: Recognition

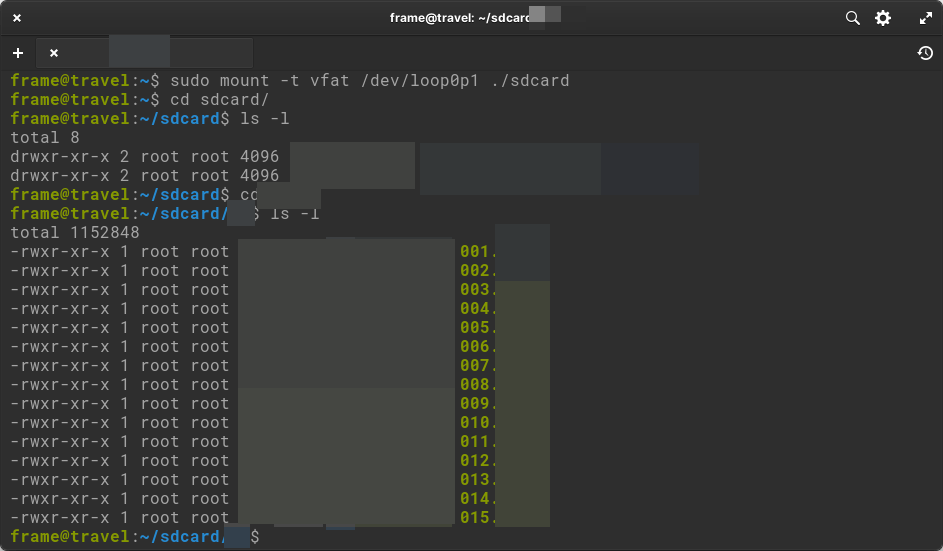

We could have started anywhere, but I suppose that due to our forensic training, we began by cloning the SD card, mounting it and seeing what we found inside.

We saw that it was a 4GB SD card with a single FAT32 partition, which gave us easy access to the file system contained on it.

At that time, we knew that the projector came with 15 preloaded content files, but that only gave access to one specific file via the physical cartridge provided, which acted as a kind of authorization token. We also knew that all the files were encrypted/compressed/obfuscated in some way, making them impossible to play directly.

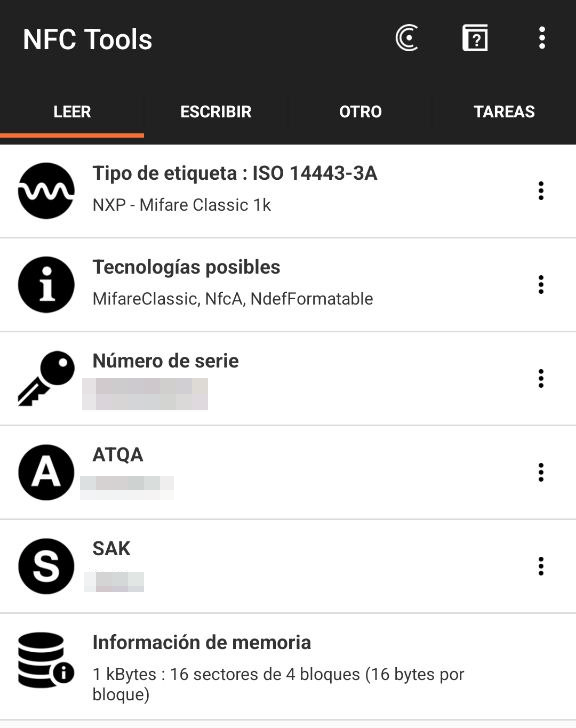

So we looked at the physical token: a piece of gray plastic. The first thing we tried was reading the token with an iPhone, which resulted in complete failure. This made us wonder if we were dealing with some esoteric technology, but since we know that iOS is notoriously limiting for this kind of NFC work, it didn’t take much effort to borrow an Android and install NFC Tools.

The result was immediate.

Phase 2: Obfuscation Masquerading as Crypto

We had to choose to continue along one of the two paths. Between the tag and the files, we chose to start with the files.

Here, I’m compelled to issue a disclaimer. I’m sorry if my analysis offends the creators, but calling it cryptanalysis would offend cryptographers and it would make Alan Turing turn in his grave, so I refuse to call it cryptography and I’m much more inclined to call it a joke.

With that said, I think the best way to explain the magnitude of the challenge we faced in reversing the file obfuscation is to show a hexdump of the first 128 bytes of two files from SD.

I don’t think there’s much to say. Anyone who is even minimally familiar with Shannon and the most basic principles of cryptography knows that one of the fundamental properties of any proper ciphering algorithm is the elimination of patterns and the increase of entropy.

In this case, recognizing that we’re dealing with a one-byte XOR, the value of the byte; and that once the obfuscation is removed, we’re obtaining an MP4 file is absolutely trivial. In the same way, it’s the magic of an XOR, any MP4 file can be encoded so that it can be played by the projector.

Phase 3: The Old Tech NFC Tag

Knowing that the tag was Mifare Classic 1K, we had to rely on the reference Android tool for this type of tag.

This tool allowed us to read the tag’s content without any difficulty, mainly because the tag still used factory default keys, publicly documented and supported by common tools.

Here we had a moment of doubt, thinking that perhaps the tag ID was what marked the video being played, but the fact that there was a duplicate string at 0:1 and 1:0, and that it contained several instances corresponding to the ID of the video played when this tag was placed, led us to believe that everything would be simpler.

We hypothesized that the duplicated byte acted as a file pointer and the value mapped to file in the SD card. To test this, we cloned the sector structure, and wrote the modified blocks targeting a custom file with an ID higher than those occupied.

And, to no one’s surprise (not even the children were surprised), we were right. It worked without any problems, allowing us to rewrite the cartridge itself or even create our own labels using blank MIFARE Classic 1K tags to reproduce customized content and thus fulfilling the dreams of the little ones in the house.

3# What we should learn from this toy story

This device is a perfect physical metaphor for modern development. Security is often treated as a cosmetic feature; something to paint over the functional design required by the business.

The Toy to Enterprise Translation Guide

The vulnerabilities we found here are functionally identical to the ones we find in ERPs, HR Apps, OT/IoT firmware or any other serious enterprise products which are supposed to be robust and secure.

| PROJECTOR FLAW | ENTERPRISE FLAWS | CWE |

|---|---|---|

| MIFARE Classic tag with factory/default keys | Default credentials / shared factory secrets left in production on appliances/IoT/OT (cameras, gateways, controllers, BMC/iLO/IPMI, etc.) | CWE-1392 (Use of Default Credentials) |

| No tag authentication | Systems that accept an identity/token without cryptographic proof: static bearer tokens, shared API keys, trusting device_id as identity | CWE-287 (Improper Authentication) |

| Writable tag data drives a security decision | Authorization/entitlement derived from client-controlled claims/fields: role=admin, plan=premium, entitled=true in requests or weakly validated JWTs | CWE-807 (Reliance on Untrusted Inputs in a Security Decision) |

| Tag with sequential content ID | Classic IDOR: changing invoice_id, file_id, user_id grants access because ownership/ACL isn’t enforced | CWE-639 (Authorization Bypass Through User-Controlled Key) |

| No authenticity verification of SD content | Loading firmware/config/plugins/bundles without verifying provenance (no signature/manifest verification) | CWE-345 (Insufficient Verification of Data Authenticity) |

| Encryption is a reversible 1-byte XOR wrapper | Broken/weak crypto used to satisfy “encrypted” checkboxes (homebrew obfuscation, obsolete ciphers, insecure modes) | CWE-327 (Broken or Risky Crypto Algorithm) |

The “It’s Too Cheap” Fallacy

The most common defense for this kind of engineering is cost.

It’s a cheap device, they can’t afford security.

This is false.

We identified a few of architectural decisions that would have drastically raised the difficulty for an attacker at zero hardware cost and without significant operational overhead.

| PROBLEM | $0 FIX | WHAT IT CHANGES |

|---|---|---|

| Default NFC keys | Set project-specific keys during manufacturing (requires only basic provisioning) | Kills the “generic Android app” attack; pushes attackers toward specialized tooling/time rather than casual reads/writes |

| 1-byte XOR “encryption” | Use real crypto (AES-128 or lightweight stream) and make the cartridge carry per-title key (or an IV) | SD assets become useless without the cartridge; the token stops being a pointer and becomes a key. Copying now requires cloning/extracting the original token secrets. If true anti-cloning matters, this requires an authenticated token (DESFire / NTAG 424 DNA class). Anti-cloning part is not $0, but maybe it’s a design requirement. |

| SD is trusted blindly | Embed a public key in firmware + ship a signed manifest of content hashes | Injected/modified files fail immediately because signature and hashes don’t validate. This stops “drop any file on SD and play it”. |

The constraint isn’t always money.

In practice, the real scarcity is usually planning, time and knowledge. A combination of factors that causes teams to deliver controls looking secure instead of controls that can be proven well-designed for the intended purpose.

Early Design Validation

The fix for this cheap toy (and for many enterprise systems that mirror it) is not buying expensive hardware. It’s early design validation.

Most security failures are not rooted in code; they are rooted in requirements. The code only translates what someone has thought and designed.

- Bad requirement: The system must play the file associated with the tag.

- Better requirement: The system only must play content that is authentic, and only when an authenticated token provides the key, or the IV, to unlock it.

A simple threat modeling session would have exposed these gaps before a single line of code was written.

Security is not a layer that is added at the end. It’s a set of decisions that must be made from the beginning. If the team skips it for €10, experience tells us that they will probably skip it for €100,000 as well.

4# Closing Thoughts

It took a laptop, a SD adapter, an Android phone and 60 minutes to break the entire system. No advanced knowledge, no zero-day exploit… just sit down, look around a bit and break it.

This is what makes the difference. Perfect security is unrealistic but good security is not. And here we have seen a few decisions that are really bad and, moreover, completely compromises the recurring sales business model of a large publishing group.

Everyone can draw their own conclusions. The closing image shows The NeverEnding Story on the projector. It’s a nice ending for a family evening.

It’s also an accurate name for this problem.