Neural nets assume the world is flat. Hierarchical data reminds us that it isn’t.

Neural networks are predicated on the assumption that a single function maps inputs to outputs. But in the real world, data rarely fits that mold.

Think about a clinical trial run across multiple hospitals: the drug is the same, but patient demographics, procedures, and record-keeping vary from one hospital to the next. In such cases, observations are grouped into distinct datasets, each governed by hidden parameters. The function mapping inputs to outputs isn’t universal — it changes depending on which dataset you’re in.

Standard neural nets fail badly in this setting. Train a single model across all datasets and it will blur across differences, averaging functions that shouldn’t be averaged. Train one model per dataset and you’ll overfit, especially when datasets are small. Workarounds like static embeddings or ever-larger networks don’t really solve the core issue: they memorize quirks without modeling the dataset-level structure that actually drives outcomes.

This post analyzes a different approach: hypernetworks — a way to make neural nets dataset-adaptive. Instead of learning one fixed mapping, a hypernetwork learns to generate the parameters of another network based on a dataset embedding. The result is a model that can:

- infer dataset-level properties from only a handful of points,

- adapt to entirely new datasets without retraining, and

- pool information across datasets to improve stability and reduce overfitting.

We’ll build the model step by step, with code you can run, and test it on synthetic data generated from Planck’s law. Along the way, we’ll compare hypernetworks to conventional neural nets — and preview why Bayesian models (covered in Part II) can sometimes do even better.

1. Introduction

In many real-world problems, the data is hierarchical in nature: observations are grouped into related but distinct datasets, each governed by its own hidden properties. For example, consider a clinical trial testing a new drug. The trial spans multiple hospitals and records the dosage administered to each patient along with the patient’s outcome. The drug’s effectiveness is, of course, a primary factor determining outcomes—but hospital-specific conditions also play a role. Patient demographics, procedural differences, and even how results are recorded can all shift the recorded outcomes. If these differences are significant, treating the data as if it came from a single population will lead to flawed conclusions about the drug’s effectiveness.

From a machine learning perspective, this setting presents a challenge. The dataset-level properties—how outcomes vary from one hospital to another—are latent: they exist, but they are not directly observed. A standard neural network learns a single, constant map from inputs to outputs, but that mapping is ambiguous here. Two different hospitals, with different latent conditions, would produce different outcomes, even for identical patient profiles. The function becomes well-defined (i.e. single-valued) only once we condition on the dataset-level factors.

To make this concrete, we can construct a toy example which quantifies the essential features we wish to study. Each dataset consists of observations (𝝂, y) drawn from a simple function with a hierarchical structure, generated using Planck’s law:

\[ y(\nu) = f(\nu; T, \sigma) = \frac{\nu^3}{e^{\nu/T} - 1} + \epsilon(\sigma) \]

where:

- 𝝂 is the covariate (frequency),

- y is the response (brightness or flux),

- T is a dataset-specific parameter (temperature), constant within a dataset but varying across datasets, and

- ε is Gaussian noise with scale σ, which is unknown but remains the same across datasets.

This could represent pixels in a thermal image. Each pixel in the image has a distinct surface temperature T determining its spectrum, while the noise scale σ would be a property of the spectrograph or amplifier, which is consistent across observations.

The key point is that while (𝝂, y) pairs are observed and known to the modeler, the dataset-level parameter T is part of the data-generating function, but is unknown to the observer. While the function f(𝝂; T) is constant (each dataset follows the same general equation), since each dataset has a different T, the mapping y(𝝂) varies from one dataset to the next. This fundamental structure — with hidden dataset-specific variables influencing the observed mapping — is ubiquitous in real-world problems.

Naively training a single model across all datasets would force the network to ignore these latent differences and approximate an “average” function. This approach is fundamentally flawed when the data is heterogeneous. Fitting a separate model for each dataset also fails: small datasets lack enough points for robust learning, and the shared functional structure, along with shared parameters such as the noise scale σ, cannot be estimated reliably without pooling information.

What we need instead is a hierarchical model — one that accounts for dataset-specific variation while still sharing information across datasets. In the neural network setting, this naturally leads us to meta-learning: models that don’t just learn a function, but learn how to learn functions.

Takeaway

Standard neural nets assume one function fits all the data; hierarchical data (which is very common) violates that assumption at a fundamental level. We need models that adapt per-dataset when required, while still sharing the information which is consistent across datasets.

2. Why Standard Neural Networks Fail with Hierarchical Data

A standard neural network trained directly on (𝝂, y) pairs struggles in this setting because it assumes that one universal function maps inputs to outputs across all datasets. In our problem, however, each dataset follows a different function y(𝝂), determined by the hidden dataset-specific parameter T. The single-valued function f(𝝂; T) is not available to us because we cannot observe the parameter T. Without explicit access to T, the network cannot know which mapping to use.

Ambiguous Mappings

To see why this is a problem, imagine trying to predict a person’s height without any other information. In a homogeneous population — say, all adults — simply imputing the mean might do reasonably well. (For example, if our population in question is adult females in the Netherlands, simply guessing the mean would be accurate to within ±2.5 inches 68% of the time.) But suppose the data includes both adults and children. A single distribution would be forced to learn an “average” height that fits neither group accurately. Predictions using this mean would virtually never be correct.

The same problem arises in our hierarchical setting: since a single function cannot capture all datasets simultaneously, predictions made with an “average” function will not work well.

Common Workarounds, and Why They Fall Short

Static dataset embeddings: A frequent workaround is to assign each dataset a unique embedding vector, retrieved from a lookup table. This allows the network to memorize dataset-specific adjustments. However, this strategy does not generalize: when a new dataset arrives, the network has no embedding for it and cannot adapt to the new dataset.

Shortcut learning: Another possibility is to simply enlarge the network and provide more data. In principle, the model might detect subtle statistical cues — differences in noise patterns or input distributions — that indirectly encode the dataset index. But such “shortcut learning” is both inefficient and unreliable. The network memorizes dataset-specific quirks rather than explicitly modeling dataset-level differences. In applied domains, this also introduces bias: for instance, a network might learn to inappropriately use a proxy variable (like zip code or demographic information), producing unfair and unstable predictions.

What We Actually Need

These limitations highlight the real requirements for a model of hierarchical data. Rather than forcing a single network to approximate every dataset simultaneously, we need a model that can:

- Infer dataset-wide properties from only a handful of examples,

- Adapt to entirely new datasets without retraining from scratch, and

- Pool knowledge efficiently across datasets, so that shared structure (such as the functional form, or the noise scale σ) is estimated more robustly.

Standard neural networks with a fixed structure simply cannot meet these requirements. To go further, we need a model that adapts dynamically to dataset-specific structure while still learning from the pooled data. Hypernetworks are one interesting approach to this problem.

Takeaway

Workarounds like static embeddings or bigger models don’t fix the core issue: hidden dataset factors cause the observed mapping from inputs to outputs to be multiply-valued. A neural network, which is inherently single-valued, cannot fit such data. We need a model that (1) infers dataset-wide properties, (2) adapts to new datasets, and (3) pools knowledge across datasets.

3. Dataset-Adaptive Neural Networks

3.1 Dataset Embeddings

The first step toward a dataset-adaptive network is to give the model a way to represent dataset-level variation. We do this by introducing a dataset embedding: a latent vector E that summarizes the properties of a dataset as a whole.

We assign each training dataset a learnable embedding vector:

# dataset embeddings (initialized randomly & updated during training)

dataset_embeddings = tf.Variable(

tf.random.normal([num_datasets, embed_dim]),

trainable=True

)

# Assign dataset indices for each sample

dataset_indices = np.hstack([np.repeat(i, len(v)) for i, v in enumerate(vs)])

x_train = np.hstack(vs).reshape((-1, 1))

y_train = np.hstack(ys).reshape((-1, 1))

# Retrieve dataset-specific embeddings

E_train = tf.gather(dataset_embeddings, dataset_indices)At first glance, this might look like a common embedding lookup, where each dataset is assigned a static vector retrieved from a table — but we have already discussed at length why that approach won’t work here!

During training, these embeddings do in fact act like standard embeddings (and are implemented as such). Like standard embeddings, ours serve to encode dataset-specific properties. The key distinction comes from how we handle the embeddings at inference time: the embeddings remain trainable, even during prediction. When a previously-unseen dataset appears at inference time, we initialize a new embedding for the dataset and optimize it on the fly. This turns the embedding into a function of the dataset itself, not a hard-coded (and constant) identifier. During training, the model learns embeddings that capture hidden factors in the data-generating process (such as the parameter T in our problem). At prediction time, the embedding continues to adapt, allowing the model to represent new datasets that it has never seen before. Such flexibility is crucial for generalization.

3.2 Introducing the Hypernetwork

With dataset embeddings in place, we now need a mechanism to translate those embeddings into meaningful changes in the network’s behavior. A natural way to do this is with a hypernetwork: a secondary neural network that generates parameters for the main network.

The idea is simple but powerful. Instead of learning a single function f(𝝂), we want to learn a family of functions f(𝝂; E), parameterized by the dataset embedding E. The hypernetwork takes E as input and produces weights and biases for the first layer of the main network. In this way, dataset-specific information directly shapes how the main network processes its inputs. After the first layer, the remainder of the network is independent of the dataset; in effect, we have factored the family of functions f(𝝂; E) into the composition g(𝝂; h(E)), and the task is now to learn functions g and h which approximate our data-generating process.

Here is a minimal implementation in Keras:

def build_hypernetwork(embed_dim):

"""Generates parameters for the first layer of the main network"""

emb = K.Input(shape=(embed_dim,), name='dataset_embedding_input')

l = K.layers.Dense(16, activation='mish', name='Hyper_L1')(emb)

l = K.layers.Dense(32, activation='mish', name='Hyper_L2')(l)

# Generate layer weights (32 hidden units, 1 input feature)

W = K.layers.Dense(32, activation=None, name='Hyper_W')(l)

W = K.layers.Reshape((32, 1))(W) # Reshape to (32, 1)

# Generate biases (32 hidden units)

b = K.layers.Dense(32, activation=None, name='Hyper_b')(l)

return K.Model(inputs=emb, outputs=[W, b], name="HyperNetwork")The hypernetwork transforms the dataset embedding into a set of layer parameters (W, b). These parameters will replace the fixed weights of the first layer in the main network, giving us a learnable, dataset-specific transformation of the input.

A hypernetwork maps dataset embeddings to neural network parameters. This lets us capture dataset-level variation explicitly, so that each dataset is modeled by its own effective function without training separate networks from scratch. Remarkably, despite this flexibility, all the parameters in the hypernetwork are constant with respect to the dataset. The only dataset-specific information needed to achieve this flexibility is the embedding (4 floats per dataset, in our example).

3.3 Main Network Integration

Now that we have a hypernetwork to generate dataset-specific parameters, we need to integrate them into a main network which models the data. The main network can have any architecture we like; all we need to do is to replace the first fixed linear transformation with a dataset-specific transformation derived from the embedding.

We can do this by defining a custom layer that applies the hypernetwork-generated weights and biases:

class DatasetSpecificLayer(K.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

super(DatasetSpecificLayer, self).__init__(**kwargs)

def call(self, inputs):

""" Applies the dataset-specific transformation using generated weights """

x, W, b = inputs # unpack inputs

x = tf.expand_dims(x, axis=-1) # Shape: (batch_size, 1, 1)

W = tf.transpose(W, perm=[0, 2, 1]) # Transpose W to (batch_size, 1, 32)

out = tf.matmul(x, W) # Shape: (batch_size, 1, 32)

out = tf.squeeze(out, axis=1) # Shape: (batch_size, 32)

return out + b # Add bias, final shape: (batch_size, 32)This layer serves as the bridge between the hypernetwork and the main network. Instead of relying on a single, fixed set of weights, the transformation applied to each input is customized for the dataset via its embedding.

With this building block in place, we can define the main network:

embed_dim = 4

hypernet = build_hypernetwork(embed_dim)

def build_base_network(hypernet, embed_dim):

""" Main network that takes x and dataset embedding as input """

inp_x = K.Input(shape=(1,), name='input_x')

inp_E = K.Input(shape=(embed_dim,), name='dataset_embedding')

# Get dataset-specific weights and biases from the hypernetwork

W, b = hypernet(inp_E)

# Define a custom layer using the generated weights

l = DatasetSpecificLayer(name='DatasetSpecific')([inp_x, W, b])

# Proceed with the normal dense network

l = K.layers.Activation(K.activations.mish, name='L1')(l)

l = K.layers.Dense(32, activation='mish', name='L2')(l)

l = K.layers.Dense(32, activation='mish', name='L3')(l)

out = K.layers.Dense(1, activation='exponential', name='output')(l)

return K.Model(inputs=[inp_x, inp_E], outputs=out, name="BaseNetwork")Why exponential activation on the last layer? Outputs from Planck’s law are strictly positive, and they fall like exp(-x) for large x. This choice therefore mirrors our anticipated solution, and it allows the approximately linear outputs from the Mish activation in the L3 layer to naturally translate into an exponential tail. We have found this choice, motivated by the physics of the dataset, to lead to faster convergence and better generalization in the model. Exponential activations can have convergence issues with large-y values, but our dataset does not contain such values.

To recap, the overall process is as follows:

- The hypernetwork generates dataset-specific parameters (W, b).

- The DatasetSpecificLayer applies this transformation to the input 𝝂, producing a transformed representation 𝝂’. If the transformation works correctly, all the various datasets should be directly comparable in the transformed space.

- The main network learns a single universal mapping from transformed inputs 𝝂’ to the outputs y.

By integrating hypernetwork-generated parameters into the first layer, we transform the main network into a system that adapts automatically to each dataset. This allows us to capture dataset-specific structure while still training a single model across all datasets.

Takeaway

Combining dataset embeddings with a hypernetwork allows one single-valued neural network to express a family of functions f(𝝂; E) by decomposing it into f(𝝂; E) = g(𝝂, h(E)) in which g and h are ordinary, single-valued neural networks. The first layer of the main network becomes dataset-specific; the rest behaves like an ordinary feed-forward network and learns a universal mapping on transformed inputs.

4. Training Results

With the embeddings, base network, and hypernetwork now stitched together, we can now evaluate the model on our test problem. To do this, we train on a collection of 20 synthetic datasets generated from Planck’s law as described in Section 1. Each dataset has its own temperature parameter T, while the noise scale σ is shared across all datasets.

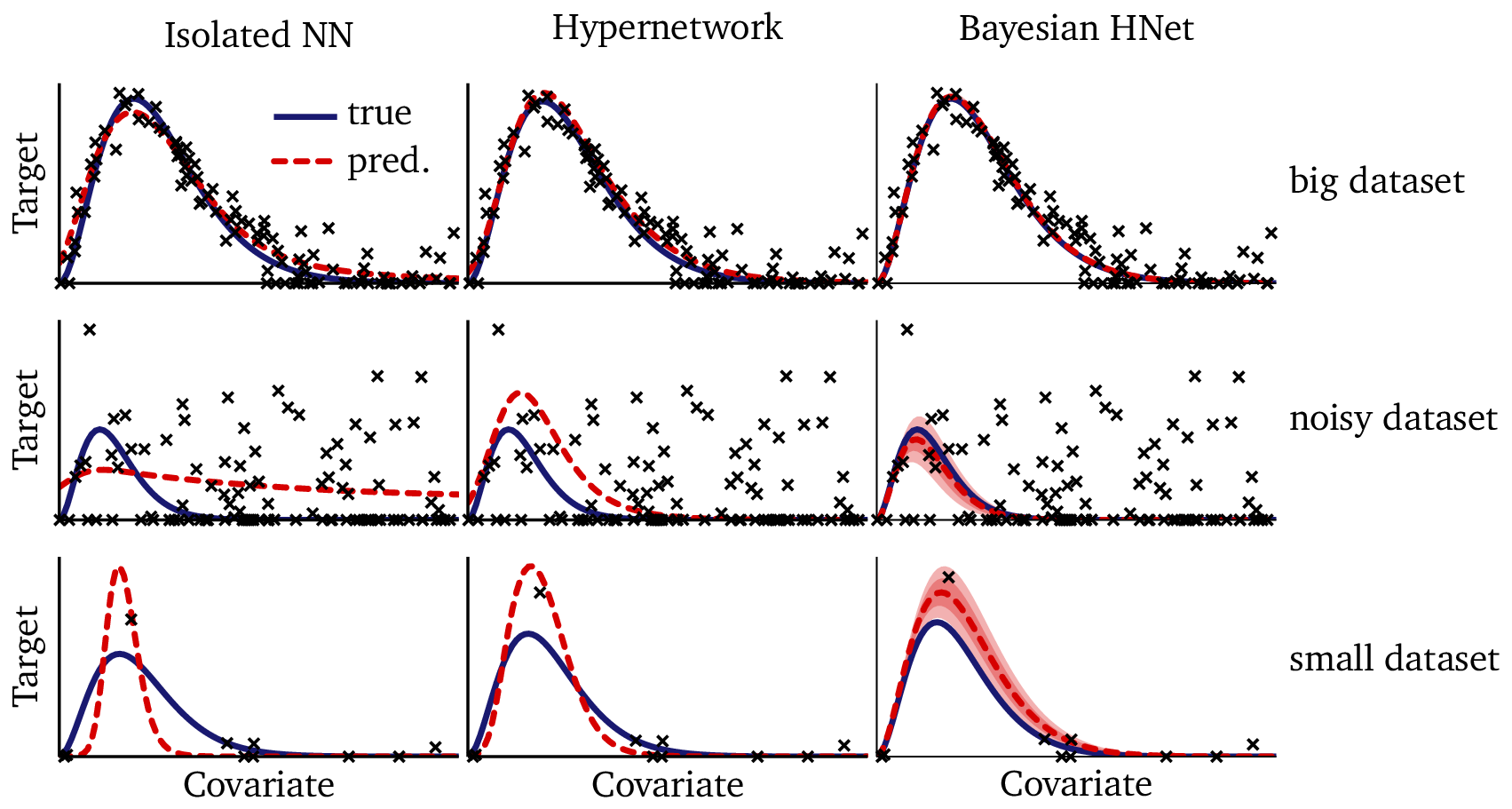

The figure below shows the training results. Each panel shows a distinct dataset from the test. In each panel,

- the Blue solid curve shows the true function derived from Planck’s law,

- the Black points shows observed training data,

- the Red dashed curve shows predictions from the hypernetwork-based model, and

- the Gold dotted curve shows predictions from a conventional neural network trained separately on each dataset.

Several key patterns are evident:

Comparable overall accuracy: In many cases (such as the 1st column of the 1st row), the hypernetwork’s predictions (red) are very similar to those of an isolated neural network (gold). This shows that, despite strongly restricting the model and removing ~95% of its parameters, sharing parameters across datasets does not sacrifice accuracy when sufficient data are available.

Improved stability: When training data are sparse (such as in the 1st column of the 2nd row, or the last column of the 3rd row), the hypernetwork over-fits considerably less than the isolated neural network. Its predictions remain smoother and closer to the true functional form, while the isolated neural network sometimes strains to fit individual points.

Pooling across datasets: By training on all datasets simultaneously, the hypernetwork learns to separate the shared structure [such as the noise scale σ, or the underlying functional form f(𝝂; T)] from dataset-specific variation (the embedding E). This shared learning stabilizes predictions across the board, but it is especially visible in the panels with particularly noisy data (such as the last column of the 2nd row, or the 2nd column of the 3rd row).

Takeaway

The hypernetwork achieves comparable accuracy to isolated networks when data are plentiful, and superior stability when data are scarce. Its advantages result from pooling information across datasets, allowing the network to capture both shared and dataset-specific structure in a single model.

5. Predictions for New Datasets

The training performance of our hypernetwork is encouraging, but the real test is how the model adapts to new datasets it has never seen before. Unlike a conventional neural network — which simply applies its learned weights to any new input — our model is structured to recognize that each dataset follows a distinct intrinsic function. To make predictions, it must first infer the dataset’s embedding.

5.1 Two-Stage Process

Adapting to a new dataset proceeds in two steps:

- Optimize the dataset embedding E’ so that it best explains the observed points.

- Use the optimized embedding E’ to generate predictions for new inputs via the main network.

This two-stage pipeline allows the model to capture dataset-specific properties with only a handful of observations, without retraining the entire network.

5.2 Embedding Optimization

To infer a dataset embedding, we treat E’ as a trainable parameter. Instead of training all of the network’s weights from scratch, we optimize only the embedding vector until the network fits the new dataset. Because the embedding is low-dimensional (in this case, just 4 floats), this optimization is efficient and requires little data to converge.

A convenient way to implement this is with a wrapper model that holds a single embedding vector and exposes it as a learnable variable:

class DatasetEmbeddingModel(K.Model):

def __init__(self, base_net, embed_dim):

super(DatasetEmbeddingModel, self).__init__()

self.base_net = base_net

self.E_new = tf.Variable(

tf.random.normal([1, embed_dim]), trainable=True, dtype=tf.float32

)

# for better performance on small datasets, use tensorflow_probability:

# self.E_new = tfp.distributions.Normal(loc=0, scale=1).sample((1, embed_dim))

def call(self, x):

# Tile E_new across batch dimension so it matches x's batch size

E_tiled = tf.tile(self.E_new, (tf.shape(x)[0], 1))

return self.base_net([x, E_tiled])

def loss(self, y_true, y_pred):

mse_loss = K.losses.MSE(y_true, y_pred)

reg_loss = 0.05 * tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(self.E_new)) # L2 regularization on E

return mse_loss + reg_lossHere, the dataset embedding E’ is initialized randomly, then updated via gradient descent to minimize prediction error on the observed points. Because we are only optimizing a handful of parameters, the process is lightweight and well-suited to small datasets.

By framing the embedding as a trainable parameter, the model can adapt to new datasets efficiently. This strategy avoids retraining the full network while still capturing the dataset-specific variation needed for accurate predictions.

5.3 Generalization

One of the most compelling advantages of this approach is its ability to generalize to entirely new datasets with very little data. In practice, the model can often adapt with as few as ten observed points. This few-shot adaptation works because the hypernetwork has already learned a structured mapping from dataset embeddings to function parameters. When a new dataset arrives, we only need to learn its embedding, rather than fine-tune all of the network’s weights.

Compared to conventional neural networks — which require hundreds or thousands of examples to fine-tune effectively — this embedding-based adaptation is far more data-efficient. It allows the model to handle real-world scenarios where collecting large amounts of data for every new dataset is impractical.

5.4 Limitations

Despite these strengths, the hypernetwork approach is not perfect. When we evaluate predictions on out-of-sample datasets — datasets generated by the same process, but not included in the training data — we observe a noticeable degradation in quality, especially on noisy data, censored data, or on very small datasets, as the following examples show:

On the one hand, this is expected: these out-of-sample datasets are extremely challenging, and no machine learning model can guarantee perfect generalization to entirely unseen functions. On the other hand, the results are a little disappointing after seeing such promising performance on the training data. While they make dataset-specific adaptation possible, the functional forms the hypernetwork learned are not always stable when faced with data from outside the training regime.

Hypernetworks enable few-shot generalization by adapting embeddings instead of retraining networks. However, their predictions degrade out-of-sample, showing that while adaptation works, we may need alternative approaches to achieve greater robustness.

The degradation we see here looks a bit like over-fitting, and it is may be that it is caused by the optimization step we run at inference time: it is possible that some other combination of step size, stopping criteria, regularization, etc. might have produced better results. However, we were not able to find one. Instead, we hypothesize that this degradation is fundamentally caused by maximum-likelihood estimation (optimization, in neural-network terms). Optimization is not only problematic at inference time, but also as a training algorithm: in a future post, we’ll explore why we believe optimization is the wrong paradigm to use in machine learning, and why maximum-likelihood estimates can cause degradation like this at inference time. In the next post we will explore an alternative technique based on Bayesian learning, which avoids optimization altogether. In the Bayesian setting, inference is not optimization but a probabilistic update, which has much better statistical behavior, and better geometric properties in high dimensions.

Takeaway

For new datasets, we only optimize a small embedding E’ (few-shot) instead of fine-tuning the whole network. It adapts quickly — but out-of-sample stability can still degrade relative to the training performance.

6. Discussion & Next Steps

The hypernetwork approach shows how neural networks can go beyond brute-force memorization and move toward structured adaptation. By introducing dataset embeddings and using a hypernetwork to translate them into model parameters, we designed a network which is able to infer dataset-specific structure, rather than simply averaging across all datasets. This allows the model to generalize from limited data—a hallmark of intelligent systems.

The results highlight both the strengths and limitations of this strategy:

Strengths

- Few-shot adaptation: the model adapts well to new datasets with only a handful of observations.

- Shared learning: pooling across datasets improves stability and reduces overfitting.

- Flexible architecture: the hypernetwork framework can, by applying the same technique, be extended to richer hierarchical structures.

Limitations

- Out-of-sample degradation: predictions become unstable for datasets outside the training distribution, especially small, censored, or noisy ones.

- Implicit structure: embeddings capture dataset variation, but without explicit priors the model has no way to incorporate explicit knowledge, and it also struggles to maintain consistent functional forms.

These tradeoffs suggest that, while hypernetworks are a promising step, they are not perfect, and we can improve upon them. In particular, they lack the explicit probabilistic structure needed to reason about uncertainty and to constrain extrapolation. This motivates a different family of models: Bayesian hierarchical networks.

Bayesian approaches address hierarchical data directly by modeling dataset-specific parameters as latent variables drawn from prior distributions. This explicit treatment of uncertainty often leads to more stable predictions, especially for small or out-of-sample datasets.

The next post in this series will explore Bayesian hierarchical models in detail, comparing their performance to the hypernetwork approach. As a teaser, the figure below shows Bayesian predictions on the same out-of-sample datasets we tested earlier:

If you compare these out-of-sample predictions to the ones made by the hyper-network, the Bayesian results seem almost magical!

Hypernetworks bring meta-learning into hierarchical modeling, enabling flexible and data-efficient adaptation. But for robustness — especially out-of-sample — Bayesian models offer distinct advantages. Together, these approaches provide complementary perspectives on how to make machine learning more dependable in the face of hierarchical data.

Takeaway

Hypernetworks bring structured adaptation and few-shot learning, but lack explicit priors and calibrated uncertainty. Next up: Bayesian hierarchical models to address robustness and uncertainty head-on.