One of the surprising (at least to me) consequences of the fall of Twitter is the rise of LinkedIn as a social media site. I saw some interesting posts I wanted to call attention to:

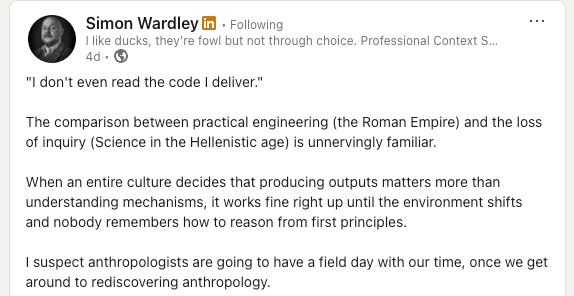

First, Simon Wardley on building things without understanding how they work:

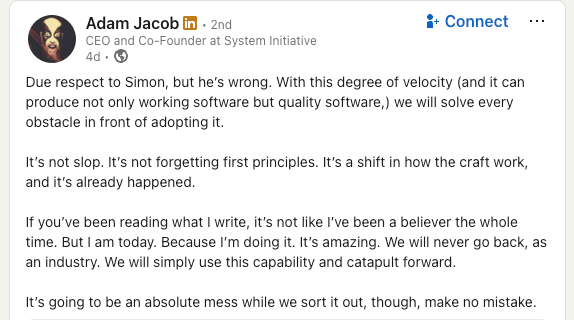

Here’s Adam Jacob in response:

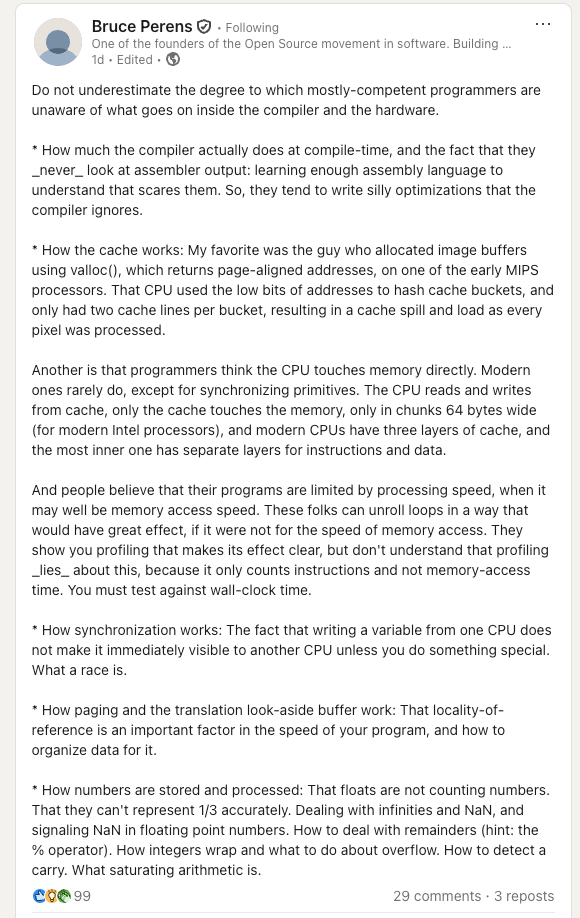

And here’s Bruce Perens, whose post is very much in conversation with them, even though he’s not explicitly responding to either of them.

Finally, here’s the MIT engineering professor Louis Bucciarelli from his book Designing Engineers, written back in 1994. Here I’m just copying and paste the quotes from my previous post on active knowledge.

A few years ago, I attended a national conference on technological literacy… One of the main speakers, a sociologist, presented data he had gathered in the form of responses to a questionnaire. After a detailed statistical analysis, he had concluded that we are a nation of technological illiterates. As an example, he noted how few of us (less than 20 percent) know how our telephone works.

This statement brought me up short. I found my mind drifting and filling with anxiety. Did I know how my telephone works?

I squirmed in my seat, doodled some, then asked myself, What does it mean to know how a telephone works? Does it mean knowing how to dial a local or long-distance number? Certainly I knew that much, but this does not seem to be the issue here.

No, I suspected the question to be understood at another level, as probing the respondent’s knowledge of what we might call the “physics of the device.”I called to mind an image of a diaphragm, excited by the pressure variations of speaking, vibrating and driving a coil back and forth within a a magnetic field… If this was what the speaker meant, then he was right: Most of us don’t know how our telephone works.

Indeed, I wondered, does [the speaker] know how his telephone works? Does he know about the heuristics used to achieve optimum routing for long distance calls? Does he know about the intricacies of the algorithms used for echo and noise suppression? Does he know how a signal is transmitted to and retrieved from a satellite in orbit? Does he know how AT&T, MCI, and the local phone companies are able to use the same network simultaneously? Does he know how many operators are needed to keep this system working, or what those repair people actually do when they climb a telephone pole? Does he know about corporate financing, capital investment strategies, or the role of regulation in the functioning of this expansive and sophisticated communication system?

Does anyone know how their telephone works?

There’s a technical interview question that goes along the lines of: “What happens when you type a URL into your browser’s address bar and hit enter?” You can talk about what happens at all sorts of different levels (e.g., HTTP, DNS, TCP, IP, …). But does anybody really understand all of the levels? Do you know about the interrupts that fire inside of your operating system when you actually strike the enter key? Do you know which modulation scheme being used by the 802.11ax Wi-Fi protocol in your laptop right now? Could you explain the difference between quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) and quadrature phase shift keying (QPSK), and could you determine which one your laptop is currently using? Are you familiar with the relaxed memory model of the ARM processor? How garbage collection works inside of the JVM? Do you understand how the field effect transistors inside the chip implement digital logic?

I remember talking to Brendan Gregg about how he conducted technical interviews, back when we both worked at Netflix. He told me that he was interested in identifying the limits of a candidate’s knowledge, and how they reacted when they reached that limit. So, he’d keep asking deeper questions about their area of knowledge until they reached a point where they didn’t know anymore. And then he’d see whether they would actually admit “I don’t know the answer to that”, or whether they would bluff. He knew that nobody understood the system all of the way down.

In their own ways, Wardley, Jacob, Perens, and Bucciarelli are all correct.

Wardley’s right that it’s dangerous to build things where we don’t understand the underlying mechanism of how they actually work. This is precisely why magic is used as an epithet in our industry. Magic refers to frameworks that deliberately obscure the underlying mechanisms in service of making it easier to build within that framework. Ruby on Rails is the canonical example of a framework that uses magic.

Jacob is right that AI is changing the way that normal software development work gets done. It’s a new capability that has proven itself to be so useful that it clearly isn’t going away. Yes, it represents a significant shift in how we build software, it moves us further away from how the underlying stuff actually works, but the benefits exceed the risks.

Perens is right that the scenario that Wardley fears has, in some sense, already come to pass. Modern CPU architectures and operating systems contain significant complexity, and many software developers are blissfully unaware of how these things really work. Yes, they have mental models of how the system below them works, but those mental models are incorrect in fundamental ways.

Finally, Bucciarelli is right that systems like telephony are so inherently complex, have been built on top of so many different layers in so many different places, that no one person can ever actually understand how the whole thing works. This is the fundamental nature of complex technologies: our knowledge of these systems will always be partial, at best. Yes, AI will make this situation worse. But it’s a situation that we’ve been in for a long time.