‘Do-it-yourself’ data storage on DNA paves way to simple archiving system

原始链接: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-026-00502-2

## 微软的千年级数据存储 微软研究院开发了一种革命性的数据存储系统,使用玻璃介质,能够保存数据至少10,000年——远远超过当前硬盘和磁带等方法的使用寿命,后者会在十年内退化。 该系统利用高能激光在硼硅酸盐玻璃方块(12厘米 x 2毫米)内创建微观形变,编码可通过显微镜读取的数据。单个玻璃方块可以存储4.8太字节的数据,相当于两百万本书。 与磁存储不同,一旦数据写入玻璃,就是永久性的,无需维护或温度控制。虽然写入和读取过程复杂,但该技术已超越实验阶段,成为“可部署的档案系统”,为关键数据备份提供安全且长期的解决方案。 这建立在之前关于耐用性和数据密度的研究之上,优先考虑实用性,并提高了写入速度和材料的负担能力。

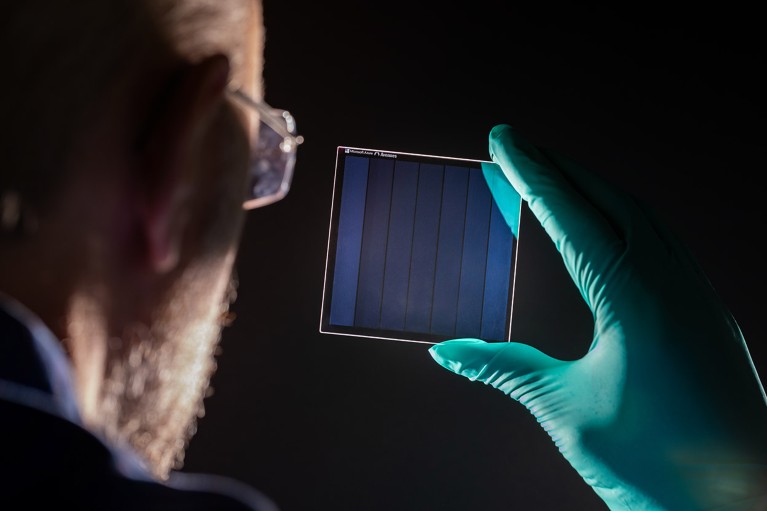

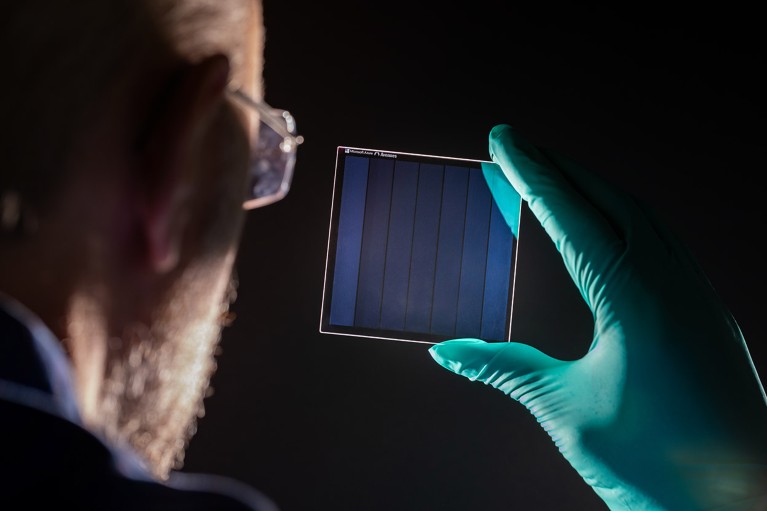

Microscoft’s glass storage method can store 4.8 terabytes of data.Credit: Microsoft Research

Researchers at Microsoft have created a data-storage system that can remain readable for at least 10,000 years — and probably much longer.

In the digital age, the need for data storage is ballooning. But current magnetic tapes and hard drives are ill-suited for long-term data storage because they degrade in about ten years. This “impressive” glass-based alternative could “in principle, act as near-permanent archival storage for backup of critical data”, says Mark Bathe, a biological engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

The Microsoft team used a high-energy laser to imprint deformations into a 3D chunk of borosilicate glass, the kind used in ovenware. Each deformation encodes data that can be read out using a microscope.

A 12-centimetrewide, 2-millimetre-thick square of the glass can store 4.8 terabytes of data, the equivalent of around two million printed books, the authors demonstrate in their paper published in Nature on 18 February1.

Writing and reading the data is considerably more convoluted than opening a file on a hard drive, but the information is much more secure. Tests suggest that the data would survive for 10,000 years at a temperature of 290 ºC and potentially for tens or hundreds of times longer at room temperature, says Richard Black, a computer scientist who led the initiative, known as Project Silica, at Microsoft Research in Cambridge, UK.

‘Do-it-yourself’ data storage on DNA paves way to simple archiving system

Although the glass method requires specialist hardware to write and read data, the paper demonstrates that glass storage has gone beyond a materials experiment and is now a “deployable archival system”, says Long Qian, a computational synthetic biologist at Peking University in Beijing.

“By showing a complete system … they have shown how this technology can truly revolutionize the data-centre industry,” says Peter Kazansky, a researcher in optoelectronics at the University of Southampton, UK, and a previous collaborator with Microsoft on glass storage.

Both magnetic tapes and hard drives encode data by using an electromagnet to magnetize tiny areas of a metal film in different orientations to represent 1s and 0s. But these tiny magnets can readily lose their magnetism, says Black, which means long-term storage requires regularly copying and re-writing the information. “The nice thing about the glass is, once it’s written, it’s immutable. You’re done,” he says. The storage for the device needs no temperature control or maintenance.

Kazansky and his colleagues developed the underlying physics behind laser-writing technology and still hold the Guinness World Record for the most durable digital storage medium for glass-based storage using fused silica. Microsoft began to build on their work in 2017. Although Kazansky’s approach maximizes durability and the density of data, in the latest work, Microsoft has gone for practicality. They explore a method that enables data to be written faster and decoded more reliably than did Project Silica’s previous iterations, says Black, and it uses cheaper borosilicate glass, rather than harder-to-make fused silica.

To encode information, the team used a laser firing in intense bursts, a few quadrillionths of a second long, to zap the glass at precise points and with a specific amount of energy. At each point, this creates a “plasma-induced nano explosion”, says Black, deforming the glass and changing how light travels through it. Researchers write the data using these tiny deformations, then read them out using a microscope that can pick up the shift in light’s behaviour as it passes through each point.