Authored by John Seiler via The Epoch Times,

Responsible businesses do regular audits of their finances to see which areas are making money and which not.

Families also do audits, if only at tax time to see how much they owe.

Contrast that with government. California State Auditor Grant Parks just came out with a new audit, “Homelessness in California: The State Must Do More to Assess the Cost‑Effectiveness of Its Homelessness Programs.”

The Joint Legislative Committee requested the audit for homeless programs ending in 2023. Mr. Parks said the audit “focuses primarily on the State’s activities, in particular the California Interagency Council on Homelessness (Cal ICH),” which coordinates the state’s programs.

This ought to be a massive scandal.

Here’s the main conclusion.

Note there’s no definitive number given, just “billions”—and even the number of programs, “at least 30,” is fuzzy:

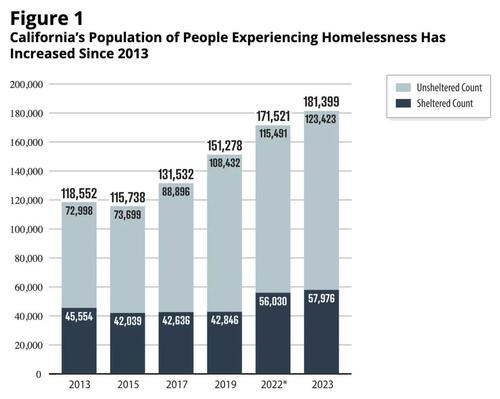

“More than 180,000 Californians experienced homelessness in 2023 - a 53 percent increase from 2013.

To address this ongoing crisis, nine state agencies have collectively spent billions of dollars in state funding over the past five years administering at least 30 programs dedicated to preventing and ending homelessness.

Cal ICH is responsible for coordinating, developing, and evaluating the efforts of these nine agencies.”

Below is the chart of the PIT—point in time—counts of the homeless:

(California State Auditor)

Also note the number went up 20 percent after Gov. Gavin Newsom took office in 2019, despite his Jan. 7 Inaugural Address that year pledging, “We will launch a Marshall Plan for affordable housing and lift up the fight against homelessness from a local matter to a state-wide mission.” The Marshall Plan was a 1948 U.S. aid program to restore economic growth to war-torn Europe.

‘Lack of Coordination’

Mr. Parks pointed to a Feb. 11, 2021 report by him, “Homelessness in California: The State’s Uncoordinated Approach to Addressing Homelessness Has Hampered the Effectiveness of Its Efforts.”

And he said Cal ICH fulfilled a legislative requirement to report its financial assessments, but did so only for the fiscal years 2018-19 and 2020-21, not after.

He added in the new report, “Further, it has not aligned its action plan for addressing homelessness with its statutory goals, nor has it ensured that it collects accurate, complete, and comparable financial and outcome information from homelessness programs. Until Cal ICH takes these critical steps, the State will lack up‑to‑date information that it can use to make data‑driven policy decisions on how to effectively reduce homelessness.”

Basically, the state government and the citizens of California have little idea where these untold “billions” of dollars to help the homeless have gone.

3 of 5 Programs Lack Enough Data

Mr. Parks said he looked more closely at five of the “at least” 30 state homeless programs. I’ll break up his paragraphs to make it more clear: “When we selected five of the State’s homelessness programs to review, we found that two were likely cost-effective: Homekey and the CalWORKs Housing Support Program (housing support program). ...

-

“Homekey refurbishes existing buildings to provide housing units to individuals experiencing homelessness for hundreds of thousands of dollars less than the cost of newly built units.

-

“The Housing Support Program’s provision of financial support to families who were at risk of or experiencing homelessness has cost the State less than it would have spent had these families remained or become homeless.

“However, we were unable to fully assess the other three programs we reviewed ... because the State has not collected sufficient data on the programs’ outcomes. In the absence of this information, the State cannot determine whether these programs represent the best use of its funds.”

The three unassessed programs were:

-

The State Rental Assistance Program, “Provides funds for rental arrears, prospective rental payments, utility and home energy cost arrears, utility and home energy costs, and other expenses related to housing incurred during or due, directly or indirectly, to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

-

The Encampment Resolution Funding Program, “Provides competitive grants to assist local jurisdictions in ensuring the wellness and safety of people experiencing homelessness in encampments by providing services and supports that address their immediate physical and mental wellness and result in meaningful paths to safe and stable housing.”

-

The Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention grant program, “Provides local jurisdictions with funds to support regional coordination and expand or develop local capacity to address their immediate homelessness challenges.”

If the rest of the “at least 30” homeless programs were examined, who knows how many would end up with too little data to assess. But if the 3 to 5 ratio holds, overall of the 30 it would be 12 assessed thoroughly, 18 not properly assessed because of too little data.

Why Is Prop. 1 Money Needed?

On March 5, California voters barely passed Proposition 1, which Gov. Gavin Newsom pushed hard. The margin was 50.18 percent yea to 49.82 percent nay. As I pointed out in my analysis in the Epoch Times, officially the bonds will cost $310 million a year for 30 years to pay back, or $9.3 billion total.

The money will come from the general fund—which currently is $73 billion in deficit, according to the Legislative Analyst. Which is why for three decades I have called bonds “delayed tax increases,” because the money has to come from somewhere.

Worse, as I noted, with interest rates staying high, the true payback amount could be higher, by some estimates as high as $12.45 billion.

How can the state spend that money when it has no idea if the unaccounted “billions” currently being spent really are helping the homeless? Are the programs good, indifferent, or bad? Is the money really helping people—or just being wasted?

It’s too bad this audit wasn’t available before the March 5 vote on Prop. 1. Likewise with the late production of the Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for fiscal year 2020-22, which came out more than a year late on March 15, just after the election, and with a “net position” $29 billion worse than previously tallied.

If voters had known how bad the state finances really were, and the inability to assess current homeless programs’ finances, would they have approved Prop. 1?

Conclusion: What Really Can Be Done?

Former state Sen. John Moorlach, for whom I worked as press secretary, has been involved in helping the homeless since when he was a Certified Public Accountant in private practice in the 1980s. Later, as an Orange County Supervisor, he was the chairman of the Orange County Commission to End Homelessness.

“Newsom is throwing money everywhere,” he said. “But, really, what are you doing? What’s the program? What are the results? How do you measure? And it’s just so sad to watch.”

If current programs aren’t working, what could?

“Recently I’ve started to started to think the way you take care of you low-income housing is you’ve got to built some nice housing, and let people move up. Then the housing in the old part of town would be the low-income housing.”

He contrasted that with the current system, in which new complexes are built specifically to house the homeless. But due to government regulations, such as prevailing wage laws, “each unit costs $900,000.”

He said often the new housing is for people who don’t even want to live inside. And older housing is where the poor used to live before.

What’s certain is the current approach of “throw money at everything—and when that doesn’t work, throw more money at it,” isn’t working. Especially because, as the new audit shows, we have no idea even where most of the money is going.