T.S. Eliot asks in the opening stanzas of his Choruses from the Rock, “where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” The passage has been called a pointed question for our time, in which we seem to have lost the ability to learn, to make meaningful connections and contextualize events. They fly by us at superhuman speeds; credible sources are buried between spurious links. Truth and falsehood blur beyond distinction.

But there is another feature of the 21st century too-often unremarked upon, one only made possible by the rapid spread of information technology. Vast digital archives of primary sources open up to ordinary users, archives once only available to historians, promising the possibility, at least, of a far more egalitarian spread of both information and knowledge.

Those archives include the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection, “over 7,500 paintings, drawings, and wax models commissioned by the USDA between 1886 and 1942,” notes Chloe Olewitz at Morsel. The word “pomology,” “the science and practice of growing fruit,” first appeared in 1818, and the degree to which people depended on fruit trees and fruit stores made it a distinctively popular science, as was so much agriculture at the time.

But pomology was growing from a domestic science into an industrial one, adopted by “farmers across the United States,” writes Olewitz, who “worked with the USDA to set up orchards to serve emerging markets” as “the country’s most prolific fruit-producing regions began to take shape.” Central to the government agency’s growing pomological agenda was the recording of all the various types of fruit being cultivated, hybridized, inspected, and sold from both inside the U.S. and all over the world.

Prior to and even long after photography could do the job, that meant employing the talents of around 65 American artists to “document the thousands and thousands of varieties of heirloom and experimental fruit cultivars sprouting up nationwide.” The USDA made the full collection public after Electronic Frontier Foundation activist Parker Higgins submitted a Freedom of Information Act request in 2015.

Higgins saw the project as an example of “the way free speech issues intersect with questions of copyright and public domain,” as he put it. Historical government-issued fruit watercolors might not seem like the obvious place to start, but they’re as good a place as any. He stumbled on the collection while either randomly collecting information or acquiring knowledge, depending on how you look at it, “challenging himself to discover one new cool public domain thing every day for a month.”

It turned out that access to the USDA images was limited, “with high resolution versions hidden behind a largely untouched paywall.” After investing $300,000, they had made $600 in fees in five years, a losing proposition that would better serve the public, the scholarly community, and those working in-between if it became freely available.

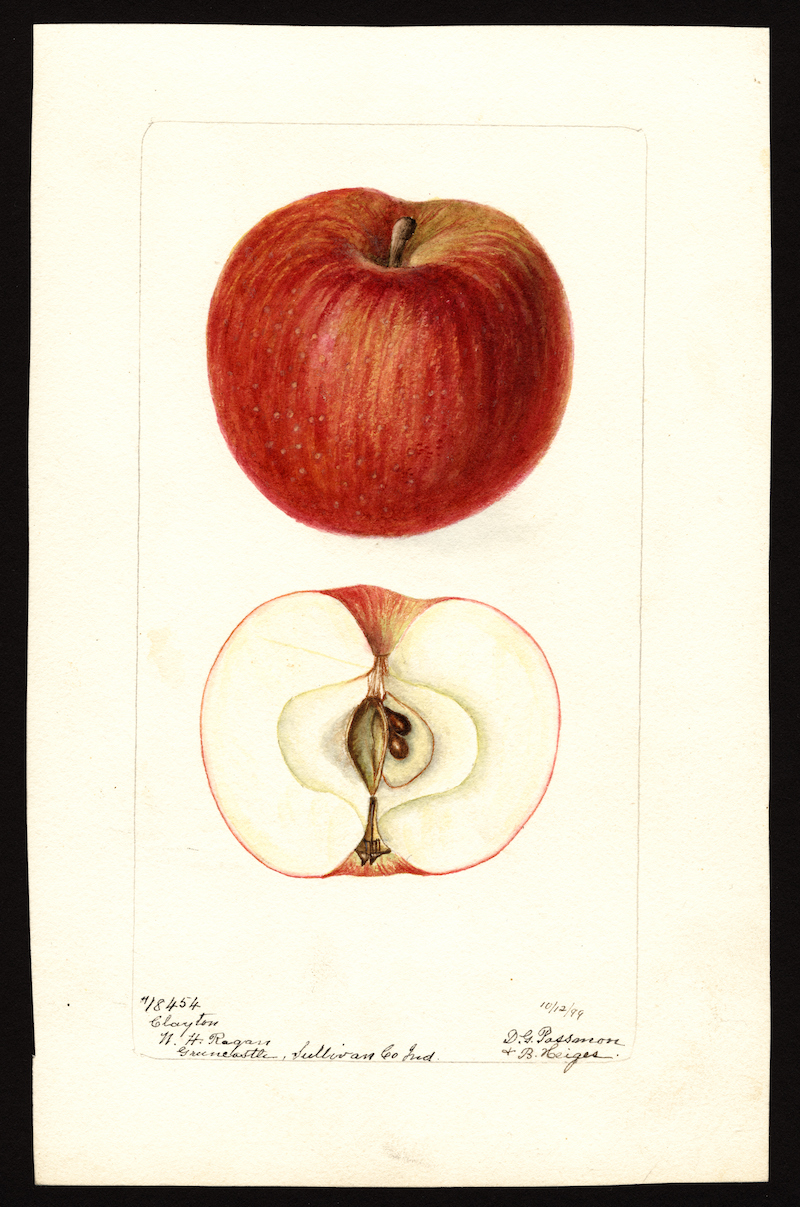

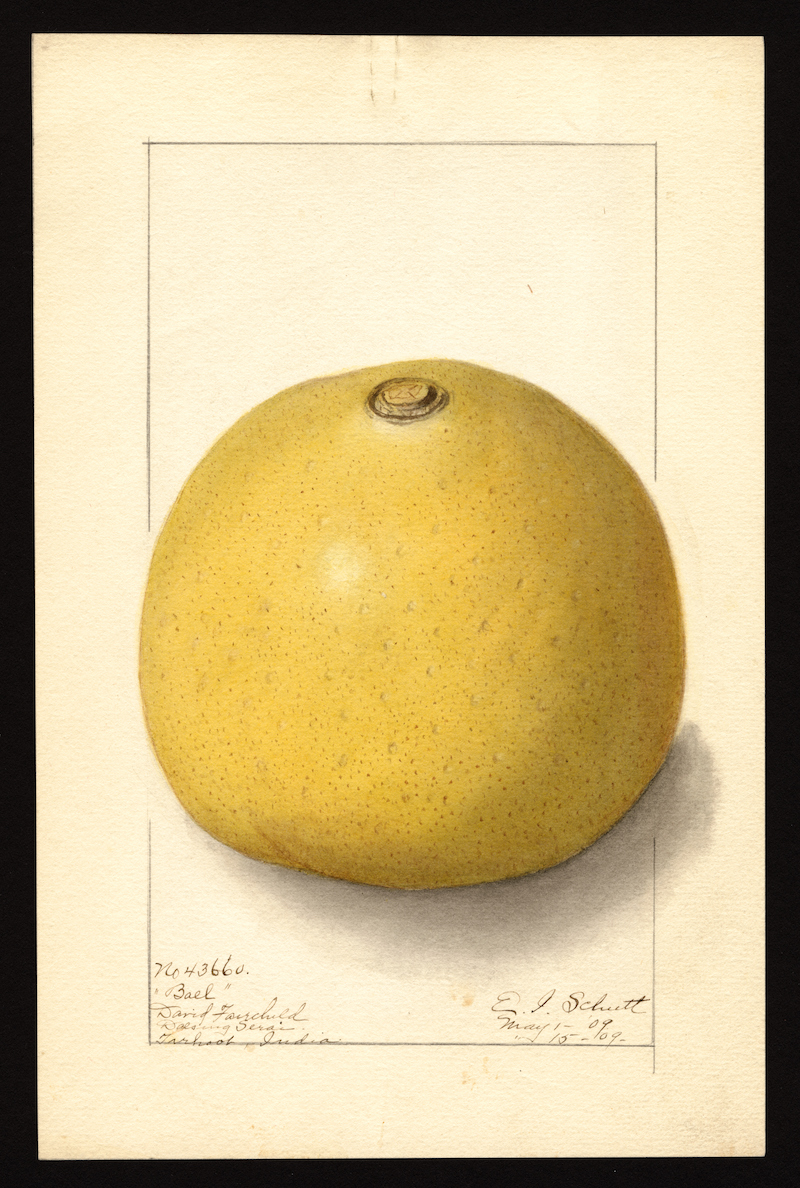

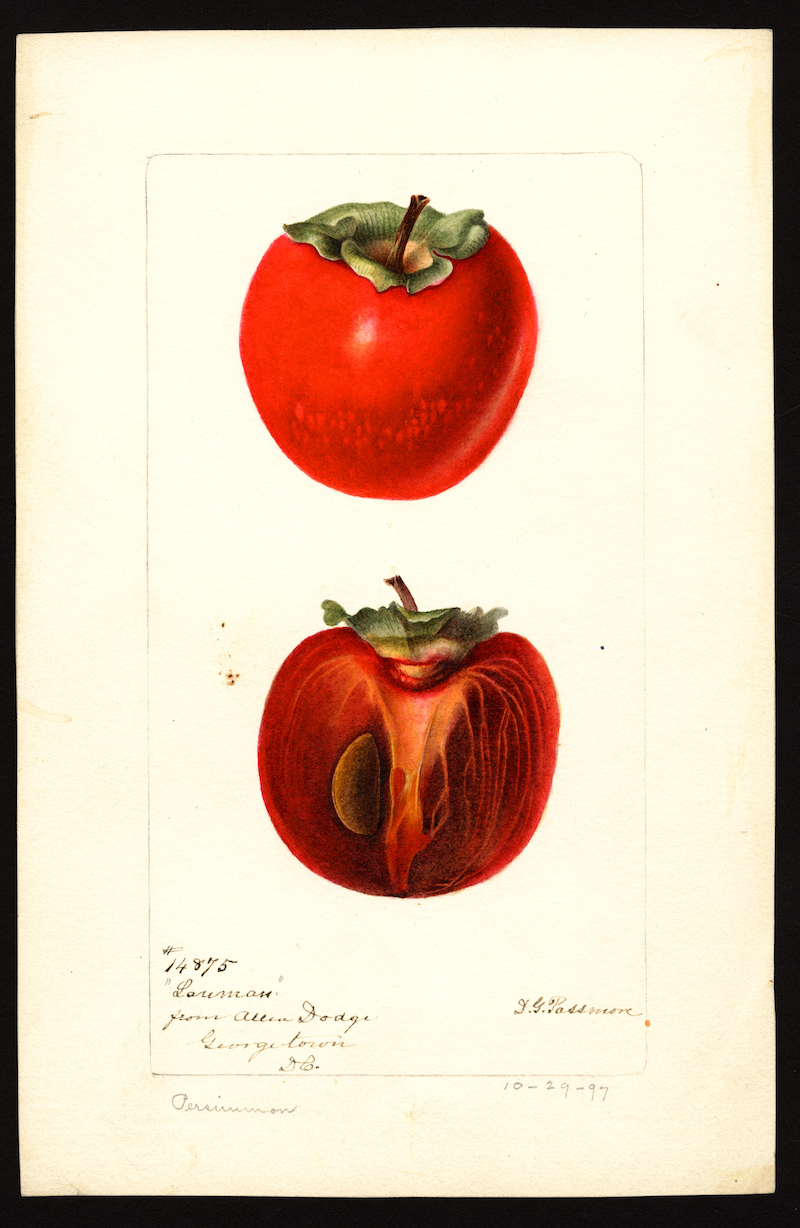

You can explore the entirety of this tantalizing collection of fruit watercolors, ranging in quality from the workmanlike to the near sublime, and from unsung artists like James Marion Shull, who sketched the Cuban pineapple above, Ellen Isham Schutt, who brings us the Aegle marmelos, commonly called “bael” in India, further up, and Deborah Griscom Passmore, whose 1899 Malus domesticus, at the top, describes a U.S. pomological archetype.

It’s easy to see how Higgins could become engrossed in this collection. Its utilitarian purpose belies its simple beauty, and with 3,800 images of apples alone, one could get lost taking in the visual nuances—according to some very prolific naturalist artists—of just one fruit alone. Higgins, of course, created a Twitter bot to send out random images from the archive, an interesting distraction and also, for people inclined to seek it out, a lure to the full USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection.

At what point does an exploration of these images tip from information into knowledge? It’s hard to say, but it’s unlikely we would pursue either one if that pursuit didn’t also include its share of pleasure. Enter the USDA’s Pomological Watercolor Collection here to new and download over 7,500 high-resolution digital images like those above.

via Morsel.

Related Content:

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness