Authored by Allen Gindler via The Mises Institute,

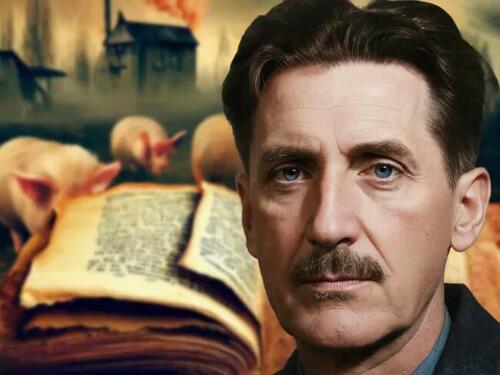

George Orwell, one of the most influential political writers of the 20th century, is widely recognized for his searing critiques of totalitarian regimes in his novels Animal Farm and 1984. Orwell’s portrayal of state control, propaganda, and the manipulation of truth has resonated with readers across the political spectrum. However, Orwell’s personal political ideology and his critiques of totalitarianism are far more complex than is often acknowledged. Rather than being a passive observer or simply an opponent of dictatorship, Orwell was deeply involved in the socialist movements of his time, aligning himself—whether accidentally or intentionally—with Trotskyist circles. Orwell was a powerful voice of the left, despite being a target in the war among socialist factions.

Orwell’s Political Ideology and Alignment with Trotskyism

While Orwell is best remembered for his criticism of authoritarianism and totalitarianism, it is essential to understand that he was, first and foremost, a committed socialist. Despite never formally joining a political party, Orwell was an active and vocal participant in the socialist movement. This may surprise those who associate Orwell solely with his critiques of state tyranny. Indeed, Orwell’s disdain for the left dictatorship did not extend to all forms of socialism, and his political writings often reflect an internal critique of socialist regimes rather than a wholesale rejection of socialist principles.

Orwell’s critique of Stalinist totalitarianism is best understood as part of a broader ideological struggle within the socialist movement itself. Specifically, Orwell’s critiques echo the views of Leon Trotsky, a key figure in early Soviet history and one of Stalin’s most prominent critics. Trotsky was a revolutionary Marxist who played a crucial role in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent civil war. He was instrumental in founding the Red Army, which secured the Bolshevik victory over the anti-communist White Army during the Russian Civil War. However, Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution” set him at odds with Stalin, who favored the consolidation of socialism in one country—namely, the Soviet Union—before pursuing global revolution. Trotsky’s insistence that socialism must be spread worldwide made him a figure of suspicion within the Soviet hierarchy. In the early 1920s, Stalin consolidated power, leading to Trotsky’s exile in 1929. Despite this, Trotsky continued to oppose Stalin’s policies from abroad, particularly through his writings.

Trotsky’s critique of Stalinism included accusations that Stalin had betrayed the original goals of the Russian Revolution. According to Trotsky, Stalin had established a bureaucratic dictatorship rather than a dictatorship of the proletariat, as envisioned by Marxist theory. He argued that Stalin’s regime represented, not the rule of the working class, but the rise of a privileged bureaucratic elite, a “nomenklatura,” that dominated Soviet society. In addition, Trotsky accused Stalin of fostering a cult of personality, suppressing political opposition, and betraying the internationalist principles of socialism.

Orwell and the Spanish Civil War

In 1936, when the Spanish Civil War broke out, Orwell made the fateful decision to join the Republican side, fighting against Francisco Franco’s Nationalista forces. What makes Orwell’s involvement particularly significant is his choice of faction. Rather than aligning himself with the International Brigades, Orwell joined the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), a Marxist faction heavily influenced by Trotskyist ideas. Orwell’s decision to fight with the POUM speaks volumes about his political leanings during this period.

The Spanish Civil War was not simply a battle between Republicans and Nationalistas; it was also an ideological battleground for various factions of the international left. The Republican side was a coalition of various socialist, communist, and anarchist groups. The POUM, with which Orwell fought, was aligned with Trotskyist and anti-Stalinist factions, while the Communist Party of Spain, supported by Stalin, took a hard line against any left-wing groups that did not adhere to Moscow’s policies. As Orwell would later write in Homage to Catalonia, his firsthand experience in Spain profoundly influenced his understanding of the brutal dynamics of power within the left. This dynamic reflects what biologists refer to as “intraspecific struggle,” where members of the same species (or political movement, in this case) compete most aggressively with each other for dominance.

While Orwell fought against Franco’s Nationalistas at the front, Stalin’s agents were conducting a purge of Trotskyist and anarchist factions behind the lines. The NKVD, Stalin’s secret police, were sent to Spain to suppress all non-Bolshevik leftist elements within the Republican forces. This included the POUM, which was eventually outlawed by the Stalinist-backed Republican leadership. NKVD agents kidnapped and killed the head of POUM, Andreu Nin. Orwell himself narrowly escaped assassination by the NKVD and covertly fled to England. These experiences deepened his disillusionment with Stalinism and reinforced his belief that the Soviet regime had betrayed the original ideals of socialism.

Orwell’s Literary Response: Animal Farm and 1984

Orwell’s experiences in Spain and his understanding of the internal conflicts within socialism found their most potent expression in his literary works. Animal Farm, published in 1945, is widely understood as an allegory of the Russian Revolution and the rise of Stalinism. Because of this, he struggled to find a publisher willing to take on the book, as many feared the political consequences of criticizing Stalin at the time of WWII. In the novella, Orwell portrays the betrayal of revolutionary ideals through the story of a group of farm animals who overthrow their human owner, only to see their new leaders—the pigs—become as oppressive as the humans they replaced. The pig Napoleon, who represents Stalin, manipulates the other animals, gradually consolidating power and rewriting the revolution’s history to justify his dictatorship.

What is often overlooked in discussions of Animal Farm is the role of Trotsky’s ideas in shaping Orwell’s narrative. The character of Snowball—who is expelled from the farm by Napoleon—represents Trotsky. Snowball, like Trotsky, is portrayed as an idealistic, but ultimately powerless figure, who is demonized by the regime in power. Orwell’s depiction of Snowball’s exile and the subsequent demonization of his legacy mirrors Trotsky’s real-life expulsion and assassination by Stalin’s agents in 1940.

In this sense, Animal Farm can be read as an artistic rendering of Trotsky’s The Revolution Betrayed (a critique of Stalinism from the left), with Orwell using the fable to illustrate the broader betrayal of socialist ideals by Stalin’s regime. Yet, Orwell could not grasp that if Trotsky had been the head of the Soviet Union, his regime might have been even more ruthless than the one Stalin built. Proletarian dictatorship is no better than party dictatorship.

Orwell’s final novel, 1984, extends his critique of totalitarianism beyond Stalinism to address the broader implications of state control, surveillance, and the manipulation of truth. Although 1984 is not explicitly focused on socialist ideology, its portrayal of a dystopian world ruled by a single party—where dissent is brutally suppressed and history is constantly rewritten—draws heavily on Orwell’s understanding of the Stalinist regime. The famous phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has since become synonymous with state surveillance and authoritarianism, but in the context of Orwell’s political trajectory, it also serves as a broader warning about the dangers of unchecked power, regardless of ideological orientation.

Orwell’s Dilemma: The Limits of Socialist Critique

Despite his damning critique of Stalinism, Orwell remained a socialist until the end of his life. His disillusionment with the Soviet Union did not extend to socialism as a whole. In fact, Orwell believed that socialism could still provide the solution to the social and economic problems facing the world, provided it did not fall into the traps of authoritarianism and bureaucracy. This presents a fundamental paradox in Orwell’s thought: while he was acutely aware of the dangers of totalitarianism produced by different currents of socialism, he continued to advocate for a general utopia that, in practice, often led to the very abuses of power he critiqued.

Orwell could not comprehend that, regardless of the specific flavor of socialism —whether Trotskyist, Stalinist, or otherwise—given enough time, it would inevitably lead to the same outcome: economic stagnation, moral decadence, and repression. His deep belief in the potential of socialism, particularly in its democratic form, blinded him to the inherent authoritarian tendencies within socialist movements.

Orwell’s Legacy

George Orwell’s legacy as a writer and political thinker is marked by his commitment to socialist ideals and his fierce opposition to totalitarianism. His engagement with Trotskyist ideas, his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, and his literary responses to Stalinism reveal a nuanced understanding of the complexities within the socialist movement. While Orwell’s critiques of political tyranny remain profoundly relevant today, his continued belief in socialism—even after witnessing its failures—underscores the intricacies of his thought. Therefore, it feels somewhat awkward to rely on a socialist’s critique of the very regimes that socialism consistently produces.