Submitted by Huw Van Steenis,

Europe has a financial plumbing problem.

Nothing illustrates this better than its securitisation markets. This is such a big issue that a seemingly exotic financial tool has shot up the agenda in Brussels lately.

Securitisation is the process of transforming a bunch of smaller loans or other cash-generating assets into larger, tradable securities. Despite the lingering bad smell from the damage this caused in the global financial crisis, a trio of landmark reports by Mario Draghi, Enrico Letta and Christian Noyer have all recommended European securitisation reforms to unclog the process and help credit flow to new projects.

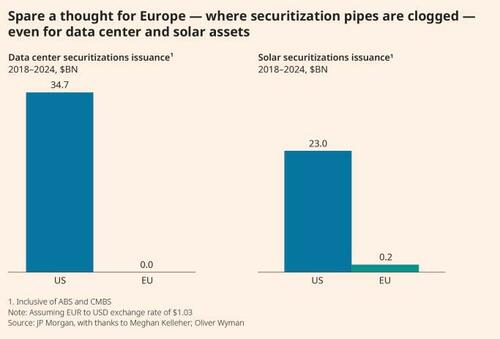

The scale of the challenge is huge. Just to take one example securitisation of US data centre debt has totalled $35bn since 2018, according to JPMorgan. The EU has yet to see a single transaction. Similarly, US solar securitisation has raised $23bn since 2018, whereas the EU saw its first and so far only residential solar securitisation in 2024, raising just €230mn.

If Europe can’t even finance these so-called strategic assets, what hope is there for midsized businesses or a broader array of assets?

That’s why the Draghi-Letta-Noyer triptych matter more than most European reports, work streams and white papers.

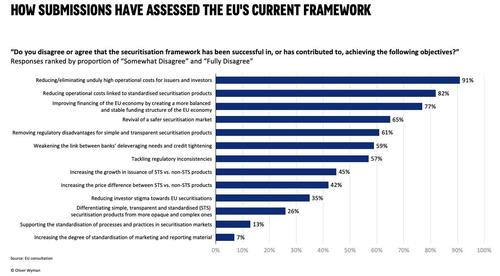

Already there is a sense that something might finally change. Late last year, the EU kick-started a short consultation process on how to make European securitisation great again. The comment letters are now in, and the EU will make recommendations before the summer.

This is overdue. Almost a decade ago, Simon Potter, formerly the markets head of the New York Federal Reserve and now vice chair of fixed income at Millennium, argued that “too much research before the crisis put too much faith in market efficiency and spent too little time exploring the detailed plumbing of the financial system.” The consultation helps address that.

However, the letters make clear that the EU probably needs to consider a system-wide response, much like a plumber would bleed every radiator to help warm a house. This won’t be easy, as individual agencies may not view the system-wide issues as their problem.

Willingness to push through will be litmus test of Europe’s determination to recalibrate regulations for growth — and close the widening gap to the US. But the comment letters do highlight four important valves that could at least be jiggled to get things going.

Valve 1: Life insurers, the missing EU lender

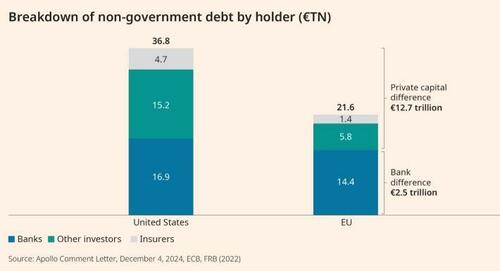

Europe has straitjacketed insurers from playing a larger role in financing the real economy via buying senior tranches of securitisations. As Apollo’s comment letter puts it:

Life insurers are particularly well-suited to finance the E.U.’s strategic, long-dated capital needs, but the European life sector currently holds only 0.33% of investment assets in securitizations vs. ~17% for U.S. life insurers despite similar industry sizes . . . The missing life insurer ‘bid’ dampens the broader E.U. securitisation market, reducing supply and demand at all points in offered securitisation tranches.

Here’s a great chart from Apollo that highlights the stark difference.

The absence of European insurers is largely driven by Solvency II capital rules, which impose punitive capital charges on securitisation — even those with investment-grade ratings that carry comparable or lower risks than corporate bonds.

Addressing this gap is vital. By recalibrating Solvency II to better align capital charges with the true risks of securitisation, European regulators could incentivise insurers to invest in these assets. Doing so would unlock a massive pool of private capital, reduce the cost of financing for businesses and infrastructure projects, and help Europe meet its strategic economic objectives.

As the Investment Company Institute argued in its submission:

The current EU prudential framework does not properly reflect these different levels of risk in the securitisation market. In certain circumstances, 10-year duration non-STS bonds, regardless of seniority in the capital structure, have a 100% capital charge. These charges are also considerably higher than those imposed by other regulatory frameworks, placing EU market participants at a competitive disadvantage.

Valve 2: STS criteria don’t work for many assets

So what’s this “STS” referenced in the ICI’s comment letter? To revitalise the securitisation market, the EU created the “simple-transparent-standardised” label – STS for short – which came into effect at the start of 2019.

This was meant to make things simpler, but many comment letters suggest it has inadvertently had the opposite effect. One of the strengths of securitisation is the breadth of stuff that can be financed, but the STS label was seemingly designed primarily for a very narrow set of bank-dominated assets. As BlackRock argued:

The regulatory standards put in place following the Global Financial Crisis represented a significant prioritisation of risk management, governance and investor protection in securitisation markets. However, the securitisation market believes that while well intended the regulations ended up being overly prescriptive and rather than reviving the market have ended up restricting it.

The optimal solution would be to streamline the STS categorisation all together via simplifying definitions, broadening STS criteria and ensuring that regulations reflect the economic risks rather than adding unnecessary complexity.

A simpler option suggested by some of the comment letters would be to just carve out asset classes that are strategically important to long-term economic growth, have a low default rate history, address asymmetry of information, and represent transactions solely between sophisticated parties that already address these risks and inbuilt protections. That way, new assets like data centres and solar projects could be included.

Valve 3: Scale up true sale securitisation

Another problem is “true sale securitisation.” This process converts illiquid assets into tradable securities and is a proven mechanism for mobilising capital.

Unlike synthetic securitisation — or Europe’s €2.4tn covered bond market — this enables banks to offload loans completely, freeing up balance sheets to support further lending while connecting investors to a broader range of financing opportunities.

The EU lags far behind the US in this critical area, with just €440bn in true sale securitisation outstanding, compared with approximately €2.8tn in the US — a 6.5-fold difference. The discrepancy underscores how underutilised this financial tool remains in Europe.

Closing this gap is essential to boosting Europe’s economic vim. With a better securitisation framework, the EU could potentially unlock over €1tn in additional financing, according to Apollo’s estimates.

The irony is that as banks struggle to issue true sale securitisation in size, they instead end up creating more opaque “synthetic risk transfers”. Moreover, true sales are simpler, have a more direct impact on credit availability in the economy and at the same time reduce interconnected risk to the banking system.

Valve 4: Streamline paperwork and due diligence

The current due diligence framework for securitisation is too costly and complex, discouraging investment, especially in the secondary market. The EU rule book shouldn’t require investors to verify regulatory compliance already handled by other regulated entities, the International Capital Markets Association argued in its response.

This is a point European Cooperative Banks make too, arguing that the due diligence requirements are “too complex and involve many overlapping reporting requirements, creating a significant obstacle for the full development of the market” — particularly for smaller businesses.

The European Fund and Asset Management Association argues the paperwork is also disproportionate and overly proscriptive:

Many of our members have explained that, for certain types of securitisations such as CLOs and CMBS, the quarterly granular reporting templates mandated under the SECR are not fit for purpose.

There are naturally a host of other suggested valves that could be adjusted, such as limits on mutual fund ownership, what is considered a liquid asset for a bank, and bank retention rules.

But the above four seem to be the main ones Europe should focus on, judging by the comment letters.

Where next?

So will the Commission accept these recommendations? It’s hard to ignore the fact that Europe has been talking about “capital markets union” for over a decade, but periodic tweaks have failed to grasp the nettle. The comments certainly underscore how frustrated market participants are.

In the most recent review of securitisation in 2022 the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority argued that there was insufficient demand from insurers to merit change.

However, the Association for Financial Markets in Europe, an umbrella trade group, suggested in its latest response that this is simply not true:

We have had categoric feedback from insurers that there would be material interest in securitisation investments, across the capital structure if it were not for the elevated capital charges associated with securitisation positions vs vanilla credit (on a like-for-like rating basis).

In fact, over 40 groups or institutions which responded to the Commission’s request for comment argued that the Solvency II rules are an impediment to the market.

Will something actually change this time? Who knows, but for the first time in a long time there seems to be some guarded optimism.

At Davos this year, Nicolai Tangen, the head of the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, went around saying that the restoration of Notre-Dame was Europe’s greatest success story of the past five years — and it happened simply because almost all regulation and rules were negated for the rebuild. “It is unbelievable what Europe can achieve if they are allowed to,” Tangen argued.

Europe needs a more flexible financial market to finance innovation and growth. Closing the gap to a buoyant and deregulating US won’t be easy. But unclogging the securitisation market would be a great to start.