Mulligan worked with Rana Dajani, Ph.D., a molecular biologist at Hashemite University in Jordan, and anthropologist Catherine Panter-Brick, Ph.D., of Yale University, to conduct the unique study. The research relied on following three generations of Syrian immigrants to the country. Some families had lived through the Hama attack before fleeing to Jordan. Other families avoided Hama, but lived through the recent civil war against the Assad regime.

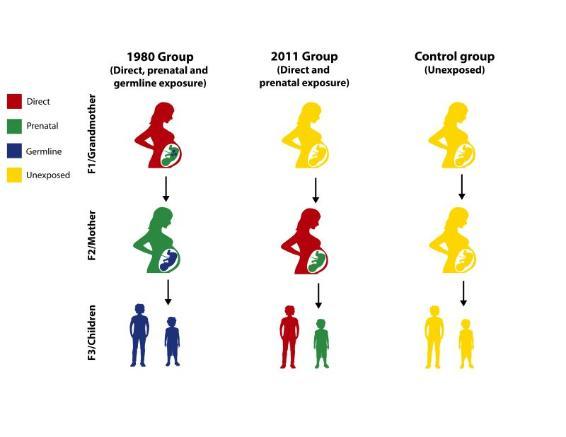

The team collected samples from grandmothers and mothers who were pregnant during the two conflicts, as well as from their children. This study design meant there were grandmothers, mothers and children who had each experienced violence at different stages of  development.

development.

A third group of families had immigrated to Jordan before 1980, avoiding the decades of violence in Syria. These early immigrants served as a crucial control to compare to the families who had experienced the stress of civil war.

Herself the daughter of refugees, Dajani worked closely with the refugee community in Jordan to build trust and interest in participating in the story. She ultimately collected cheek swabs from 138 people across 48 families.

“The families want their story told. They want their experiences heard,” Mulligan said.

Back in Florida, Mulligan’s lab scanned the DNA for epigenetic modifications and looked for any relationship with the families’ experience of violence.

In the grandchildren of Hama survivors, the researchers discovered 14 areas in the genome that had been modified in response to the violence their grandmothers experienced. These 14 modifications demonstrate that stress-induced epigenetic changes may indeed appear in future generations, just as they can in animals.

The study also uncovered 21 epigenetic sites in the genomes of people who had directly experienced violence in Syria. In a third finding, the researchers reported that people exposed to violence while in their mothers’ wombs showed evidence of accelerated epigenetic aging, a type of biological aging that may be associated with susceptibility to age-related diseases.

Most of these epigenetic changes showed the same pattern after exposure to violence, suggesting a kind of common epigenetic response to stress — one that can not only affect people directly exposed to stress, but also future generations.

“We think our work is relevant to many forms of violence, not just refugees. Domestic violence, sexual violence, gun violence: all the different kinds of violence we have in the U.S,” said Mulligan. “We should study it. We should take it more seriously.”

It’s not clear what, if any, effect these epigenetic changes have in the lives of people carrying them inside their genomes. But some studies have found a link between stress-induced epigenetic changes and diseases like diabetes. One famous study of Dutch survivors of famine during World War II suggested that their offspring carried epigenetic changes that increased their odds of being overweight later in life. While many of these modifications likely have no effect, it’s possible that some can affect our health, Mulligan said.

The researchers published their findings, which were supported by the National Science Foundation, Feb. 27 in the journal Scientific Reports.

While carefully searching for evidence of the lasting effects of war and trauma stamped into our genomes, Mulligan and her collaborators were also struck by the perseverance of the families they worked with. Their story was much bigger than merely surviving war, Mulligan said.

“In the midst of all this violence we can still celebrate their extraordinary resilience. They are living fulfilling, productive lives, having kids, carrying on traditions. They have persevered,” Mulligan said. “That resilience and perseverance is quite possibly a uniquely human trait.”