This post will describe how I design my programs in Go. I needed this for work, and while I searched for a link, nothing quite fits my coding practices out there. The word “Layered” can pull up some fairly close descriptions, but I want to lay out what I do.

Deriving Some Requirements

Go has a rule that I believe is underappreciated in its utility and whose implications are often not fully grasped, which is: Packages may not circularly reference each other. It is strictly forbidden. A compile error.

Packages are also the primary way of hiding information within Go, through the mechanism of exported and unexported fields and identifiers in the package. Some people will pile everything into a single package, and while I’m not quite ready to call this unconditionally a bad idea, it does involve sacrificing all ability to use information hiding to maintain invariants, and that is a heck of a tool to put down. At any sort of scale, you’d better have some concept of the discipline you’re going to replace that with.

So for the purposes of this discussion, I’m going to discard the “one large package approach”.

We also know that Go uses a package named main that contains a

function named main to define the entry point for a given

executable. The resulting package import structure is a directed acyclic

graph, where

the packages are the nodes and the imports are the directed edges, and

there is a distinguished “top node” for each executable.

So how do I deal with this requirement in Go?

Layered Design In Go

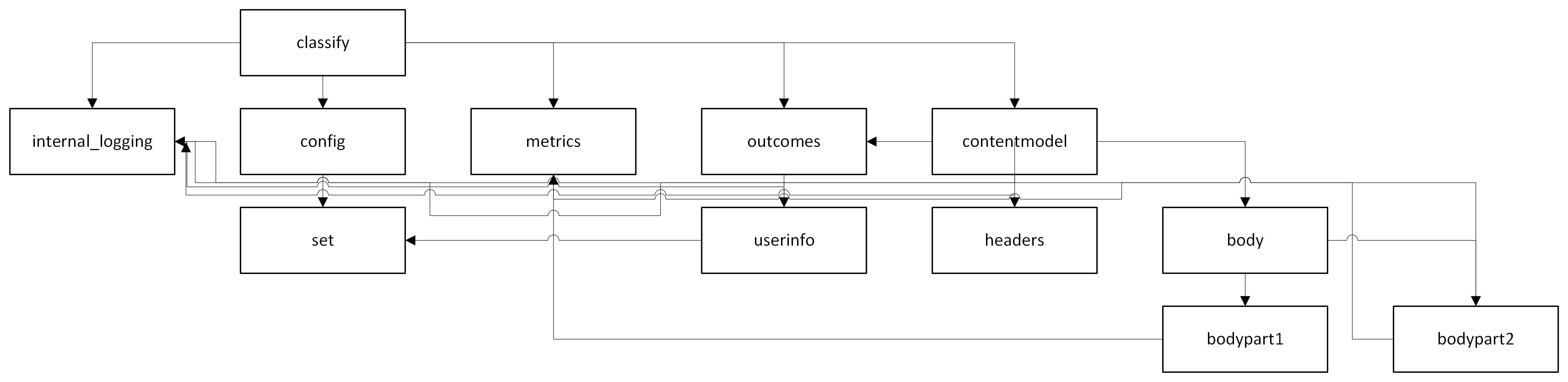

This is a portion of a package hierarchy extracted from a real project, with many of the names substituted and rubbed off, but the relationships are approximately correct:

All imports of external modules are automatically not part of a loop in the base package, so we can just look at the import patterns of the application currently being written. Since loops are forbidden that implies there must be packages that do not import any other package in the application. Pull those out and put them on the bottom:

There is now a set of packages in the remaining set that only reference the packages we just pulled out and put on the bottom. Put them in their own layer:

You can repeat this process until you’ve layered everything by the depth of the import stack:

All package imports now point downwards, though it can be hard to tell.

If you look at the bottom, you see very basic things, like “the package that provides metrics to everything else”, “the package that refines the logging for our system”, and “a set data structure”.

These are composed up into slightly higher level functionality that uses logging, metrics, etc. and puts together things like header functionality, or information about users (imagine permissions or metadata are stored here).

Throughout this post I will refer “higher level packages”; in this

case, it literally refers to the way packages will appear “higher” on

this graph than any package it imports. It is not the definition of

“higher” we often use to mean “higher level of abstraction”; yes,

if a package offers a “higher level of abstraction” it will generally

of necessity also be a “higher level package”, but a

“higher level package” is often just a package that is using the lower

level package, not an abstraction, e.g., a “crawler” may have

net/http show up as a “lower level package” but a crawler is not any

sort of abstraction around net/http so much as it is just an

application that is using net/http.

These things are then composed into higher layer objects, and so forth, and so forth, until you finally get to the desired application functionality.

This Is Descriptive, Not Prescriptive

If you are the sort of person who reads things about software architecture, you are used to people making prescriptive statements about design. For instance, one such statement I found in another article about layered design in Go has the prescriptive statement that layers should be organized into very formal layers, and that no layer should ever reach down more than one level to import a package. That is not a requirement imposed by Go, it is a prescriptive statement by the author. You can see in my graph above I don’t agree with that particular prescription, as I have imports that reach down multiple levels.

However, the previous section is not prescriptive. It may sound like prescriptions you’ve heard before, but it’s actually required. You can graph all Go modules in the layers I described. It’s a mathematical consequence of the rules for how packages are allowed to import each other. It is descriptive of the reality in Go.

Which means that any other prescriptive design for a Go program must sit on top of this structure. It has no choice. It may not be necessary, but it is certainly convenient in MVC design for the Model, View, and Controller to be able to mutually reference each other, at least a little. In Go, that’s not an option, if you want them separate from each other. You can do MVC, but you must do “MVC on top of Go layering”. If you slam all of the MVC stuff into one package for convenience, or for it to work at all, you’re increasing the odds that you’ll still end up with circular loops between the packages implementing other related Models or Views or Controllers.

You can “hexagonal architecture”, but you must do it on top of Go layering.

You can do any design methodology you want, but it must always rigidly fit the layered design described in the previous section, because it is not an option.

They do not all go on top of this design constraint equally well.

So What’s The Best Prescription?

Naturally, this raises the question of what’s the best methodology to sit on top of this.

My personal contention is that the answer is “none”. This is a perfectly sensible and adequate design methodology on its own.

It harmonizes well with a lot of the points I make in Functional Programming Lessons in Imperative Code. Particularly the section about purifiable subcomponents and the ability to compose multiple component’s purifications together. If you design a shim for the metrics for testing the metrics in a pure manner, you can then use that to design the purification for the bodypart2 above. Then you can use that to design the purification for the body package, which can then be fed into the classify package, and through all that, you can get classification tests that don’t have to depend on any external state, despite the fact it is sitting on top of a lot of other packages.

Sometimes a purification component will “absorb” the tree under it, so for instance, the contentmodel module may absorb all metrics and other packages into itself so the contentmodel can ignore all that and just use the test shim provided by the contentmodel package. Other times it may be necessary to have multiple shims related to the packages being imported. They’re already coupled by the import, so this is not additional coupling. Generally it’s a bit of both in my experience.

Any codebase can be decomposed this way with enough work. The work can be nontrivial, but it gets a lot easier as you practice.

My favorite advantage of this methodology is that for any package you point at, there is a well-defined and limited number of packages you need to understand in order to understand the package you are looking at, even considering the transitive closure of imports. It is effectively impossible to write code that requires you to understand the entire rest of the code base to understand it, because you can’t circularly loop in all the important code in the entire code base accidentally.

As code scales up, this strongly affords a style in which packages generally use only and exactly what they need, because otherwise they become too likely to participate in a circular import loop at some point.

Local Prescriptions

That’s not to say that there aren’t high level designs that can be helpful. Web handlers can use some higher level design patterns. Database-heavy applications may bring in some higher level patterns. The code base I extracted the diagram I used earlier from has a plugin-based architecture in which a particular data structure is flowed through a uniform plugin interface which has a few dozen implementations on it. However, these can be used in just the parts of the code base that make sense.

I don’t think it’s a particularly good idea to try to force any other architecture on Go programs at the top level. Isolate them to parts of the codebase where they make sense. At the very least, if one is going to impose an architecture on to a code base, it needs to be one that came from a world that has a similar circular import restriction, whether imposed by the language or self-imposed, as I think methodologies that implicitly incorporate the ability to have circular imports in them tend to scale up poorly in Go.

Avoiding Circular Dependencies

If circular dependencies are impossible in Go, how do we deal with them?

There are multiple solutions, depending on exactly what your code base is trying to express. I’ll go over some of them below, but first, there’s a step to do first: When a circular dependency arises in your code base, you must deeply analyze it and figure out exactly where the circular dependency arises from.

I will not be so dogmatic as to say that every language should be programmed without circular import loops, but I do think they are something that should be minimized in every language. Pervasive circular loops in a code base eventually make it impossible to understand the code base without understanding the code base. This poses… logical difficulties. Fortunately, the real situation is never so stark as that, and one can eventually work one’s way up to understanding even such a code base, but it is going to be a much more difficult task for the pervasive circularity. So the techniques discussed below are generally useful, even if you aren’t being forced into using them. For non-Go languages, for the word “package”, read “whatever your primary information hiding mechanism is”, be it classes, modules, or some other word.

It is not enough to say “this package is circularly depending on that package”. It isn’t even enough to say that this data structure is depending on that one. It isn’t even enough to say that this method depends on that method. You need to trace it down to what bits and pieces of a structure, specific functionality the code is embodying. Break it down as finely as possible, because as you ponder how to fix it, you may well be breaking the code up along the lines you discover.

In general, when you come across a circular import error in the compiler, it will be because you added some new code that created some new dependency that turned out to be circular. In the discussions below, I will refer to this as the “new circular code”. Upon analysis, you should also be able to identify some particular set of variables and bits of code that are the most modifiable aspect of the circular dependency, which I will call the “breakable link” in the discussions below.

Packages aren’t allowed to circularly reference each other, but generally what is causing the circularity is much smaller than the entire package.

Generally, if you can do one of these refactorings, you should, because the resulting code will increase in conceptual clarity and have a stronger design. It often as a side effect ends up reducing the size of an interface of a package as it moves bits out of the exported public interface that turn out not to belong there. Often if you listen to the code, it tells you that it is wanting these things.

These are listed in roughly the order you should prefer them:

Move The Functionality

Unfortunately, this is not the most common in my experience, but it is also the most important when it can be done. Sometimes after you analyze the situation, you will find that the bit that is causing circularity is simply in the wrong place. It probably belongs in the same location as the new circular code.

This may involve slicing apart an existing conglomeration of functionality. It could be three fields in a larger struct that turn out to still belong together, but not to belong to the larger struct at all. You may be slicing out bits of code and a field here and a field there. It won’t just be about moving entire types around.

This will hold true for all the techniques below, so I’m not going to mention this again and again. I just can’t emphasize enough that this does not simply involve moving entire types around. You can even have cases where you need to split something that looks like an atomic field in half, though that’s rare. You need to get very granular.

In the rough and tumble of greenfield implementation, I find this happens a lot initially as I am feeling out the correct structure. Once past that phase though, this becomes rare. Still, if you can do it, this is the best move, not just because it breaks the circularity, but because it has the strongest outcome on the package conceptual clarity I was talking about. A wholesale removing of the concept that didn’t belong in the breakable link into the place it belongs is, in the long term, a huge win for the code base.

Create A Third Package That Can Be Imported For The Shared Bit

If a package is reaching for something that lives in another package that results in a circular dependency, consider moving that thing into a new third package that both can import.

This happens for me most often when I was banging away, implementing

some particular functionality, and I needed some particular type,

let’s say Username, and since nothing else yet needed it, I just

dropped it into the package that needed it. As the program grows,

eventually something else wants to reference the Username in such a

way that it causes circularity. But Username should generally be

just a validated string of some sort. It can almost certainly be moved

into its own package.

The most likely reason you’re reluctant to do this… ok, well, honestly, the most likely reason is that fundamental laziness we all share and just not wanting to make the change at all… but the second most likely reason you’re reluctant to do this is that having an entire package for a single type like this feels like bad design.

However, I suggest that you learn to just do it anyhow, because in my experience, the vast majority of the time, if you could see how that new package is going to evolve, it will turn out that this new type is not going to live there alone forever, and indeed, probably not for very long at all. Of all the times I’ve done this, I think only once or twice have I ended up with a package that ended up with just one type in it by the time the program finally “settled”. Try to think about packages not just as snapshots in time but in terms of their evolution through time. It is almost always the case that rather than an isolated type or value, what you have is the first exemplar of some new non-trivial concept your package will shortly start to embody in a more complicated and complete sense.

A New Third Package That Composes The Circular Packages

This is much like the previous case, but moves in the other direction. If you have two packages circularly depending on each other for some purpose, you may be able to extract out the dependency and turn it into something that uses the two packages to achieve the task that requires the circularity.

I use this less often after I got used to designing architectures natively in Go. However, before then, I naturally brought in my old inheritance-based object oriented architecture, and that makes it easy to expect architectures that deeply depend on circularity to come into play.

Consider this perfectly sensible example from the ORM world. You have

a Category in a package, representing a category table in the DB, and

a BlogPost in a package. Each has a many-to-many relationship with

the other, and as such the .Save() operation for each ends up

depending on other, creating a circularity.

What I do in these cases is usually make Category and BlogPost

effectively dumber; I break away from them the idea that they know how

to “save” themselves. I create a Category and a BlogPost that are

just the data structures they represent. A higher package can tie them

together through a many-to-many relationship, and a yet higher package

will be the thing that “knows” how to load them from the DB and save

any changes. That top-level package may get assistance from the

lower-level values through various custom interface methods like

UnmarshalFromDB or something.

(This doesn’t work terribly well with ORMs, but, well, this is

technically one of the many many reasons I tend to avoid them. I don’t

like the way they make every object have to “know” about the DB in

order to have one in hand. This is one of the more common

manifestations of the whole you wanted a banana but what you

got was a gorilla holding the banana and the entire

jungle

problem. The layered design in Go is hostile to this approach because

the more of the jungle you end up with the more likely you have a

circular dependency, with odds rapidly approaching one. Go almost

forces you to have Bananas and Gorillas that can be in isolation,

and expressing relationships in higher level packages… but it

doesn’t fully force it, and you can still fight it. You won’t have a

good time of it, though.)

Interface To Break The Dependency

If a circular dependency results from taking some type that one of the circular bits of code is going to call methods on, and the circularity comes from the reference to the concrete type itself, you can break the circularity by having one of the places involved in the circular reference take an interface instead. That is, if you have something like

func (ur UserRef) MyUserIsAdmin(adminDB users.DBList) bool {

return adminDB.Exists(ur.User)

}and that is somehow a circular reference, you could consider:

type UserList interface {

Exists(username string)

}

func (ur UserRef) MyUserIsAdmin(adminDB UserList) bool {

return adminDB.Exists(ur.User)

}This is not always a full solution. If the interface needs values from that package as arguments or returns them as parameters this may still leave a circular reference behind. However, even in these cases, interfaces can still be a part of the solution.

You may need to create a new method that an interface can implement. A common instance of this in Go is if the circular reference is trying to get an exported field of some other struct. It is fine to take that field, unexport it, and wrap it behind a method, just so you can then use an interface to break the circular reference chain.

It is also worth pointing out that this is further down the list for a reason. While interfaces may loosen the relationship between the two packages enough to avoid being a circular dependency, it still creates a relationship of a sort between them. While my example above intrinsically lacks context, as is the way of little example snippets, it would still suggest to me that there’s probably an improper mixing of the concept of “user” and “admin” potentially going on here that is the root cause of the circularity. Taking the time to slice packages apart into clean pieces that do not have intermixed concepts will still produce superior results.

In many cases I start pulling this out as a project matures, and it has nearly attained the correct degree of separation. Sometimes you get that last minute “oh wait, these things need to be connected after all”, and this can be a good tool to go ahead and spend some of that design capital you have accrued through being more careful earlier in the design process.

Copy The Dependency

One of the proverbs of the Go community is “A little copying is better than a little dependency.” This is usually referenced in the context of not bringing in a large library just to use a few line’s worth of code out of it, but it can apply to your own code base too. If you’re importing an entire separate package for a particular tiny snippet of code, and that code really does belong there, maybe it would just be enough to have a copy of the lines in the circular package as well.

This is also lower on the list for a reason. Do this every time you have a problem and you will have the joy of rediscovering for yourself the concept of “Don’t Repeat Yourself”. However, in my experience, about the half the time I find myself backed into this particular solution to circular dependency, as the code evolves it turns out this was false sharing and false DRY and the two copies end up non-trivially, and correctly, diverging anyhow, indicating they weren’t really the same thing after all.

Maybe They Shouldn’t Be Two Separate Packages

Finally, if none of the preceding solutions seem viable, even if you put the effort in, perhaps because the circularity is just too substantial, the answer may be that the code is telling you that this is one package after all.

I rather like breaking things into lots of packages, for lots of reasons, but every once in a while it’s true that I do get a bit too zealous and I try to break something apart that just doesn’t work separately. If this is happening to you all the time, you may still need more practice and not be doing the work necessary to have a good design, but this should happen at least sometimes in my opinion, or you’re not trying hard enough to break things up.

The larger the resulting combined package would be, the more you should fight for some other solution for breaking circular dependencies, but as with all things in engineering, it’s ultimately a cost/benefits decision.

So What’s The Difference Between This And Anything Else?

I admit I struggle to describe how this differs from other design methodologies, mostly because I’ve been doing this for too long so I’m too close to the problem, and after a while honestly all the methodologies sort of blur together into one vague blob of good design practices and the Quality Without A Name. Should this get to some link aggregator site, let me issue my own criticism in advance of anyone else that I am well aware there is still a certain fogginess to this entire post, in that I have not succeeded in providing a simple recipe that you can follow every time and I am myself dissatisfied with my own description of the benefits, despite the fact I believe I have experienced substantial benefits from taking this approach over years. Consider this an attempt to write my way to that level of clarity, and one that is not done yet.

However, this approach does produce at least one thing distinctly different from many other designs, which is that every package ends up being something useful on its own terms. For instance, consider a standard web framework with a standard ORM design. ORMs make it very easy to introduce the want-banana-get-jungle problem described above. Even architectures heavy on dependency injection can still end up making it so every service requires effectively every possible dependency and thus even though in principle everything is “purifiable”, nothing is actually usable in isolation because you still have to provide every service that exists in the system, because nothing stops this from happening if you can have circular references. In principle you can use things if you only provide their dependencies, but if “providing their dependencies” still involves providing every service in the system, it still is not truly severable.

This architecture tends to force you to narrow things down to just what they need and nothing else. If you have a system for classifying emails, it will generally just need an email and the relevant classification services you may need for an email; it won’t need the users and whether those users are admins and what the users are admins over and the forums that the users are admins over and the top posts of the forums the users are admins over. If the email classification needs to reach back up to something about those details, it’ll be isolated into interfaces that can be mocked or stubbed or whathaveyou. If you just need a user’s name, you will generally find yourself being forced to do that over an interface for “yielding a name” rather than pulling in the entire package for a user, and all of its dependencies.

Many methodologies might metaphorically object that their entire point is to produce useful things that stand on their own, but it’s really easy for them to in practice still require jungles in order to have bananas. This methodology tends to produce practically useful things in isolation.

On such occasions as I have had to split bits and pieces off into microservices from what was previously a monolith, it has been an almost mechanical process, simply following the dependencies, providing them, and ending up with a functioning service. Every once in a while I have to trim something I lazily bundled together a bit, but the system has already been pushed far in that direction so it’s not a shock to the code base. I find this is a fantastic way to design “monolithic microservice” codebases, where the microservices can indeed be pulled out later in very practical amounts of work if that is desirable.

One of the things I would not call part of this design methodology in general, but something that is a good idea for any Go package regardless of what is is doing, is to try to minimize the amount of exported stuff coming from the package. Use godoc to see what is being exported… after all, you write documentation on your code anyhow, right?… and when a package is sort of wrapping up, audit each exported symbol to see if you really need to export it. The thinner the public interface, the better this works. It is better to overzealously keep things unexported, because it is really easy to re-export something it turns out you should have simply by renaming (a rename operation your IDE should support and which is guaranteed by its nature to be isolated within your one package even if you do it manually) then to unexport something previously exported. (Your IDE should tell you if a symbol you are trying to unexport is still being used if you use its rename functionality.)

Still, I don’t deny that if you read this and either don’t feel like you have a good grasp of what I’m really talking about, or how it differs from other methodologies, or indeed whether or not it is really possible and practical, there is an irreducible degree to which you just need to try it out for yourself, even in a language other than Go. (Although if you try it in something other than Go, you need circular imports to be some sort of compile or build failure for this to work. They get sneaky!) I would recommend a greenfield project; it is possible but really quite tedious and at times difficult to tear apart an existing system written against another methodology and pull it into this one, though I think that’s just a general rearchitecting truth and not a particular problem with this.