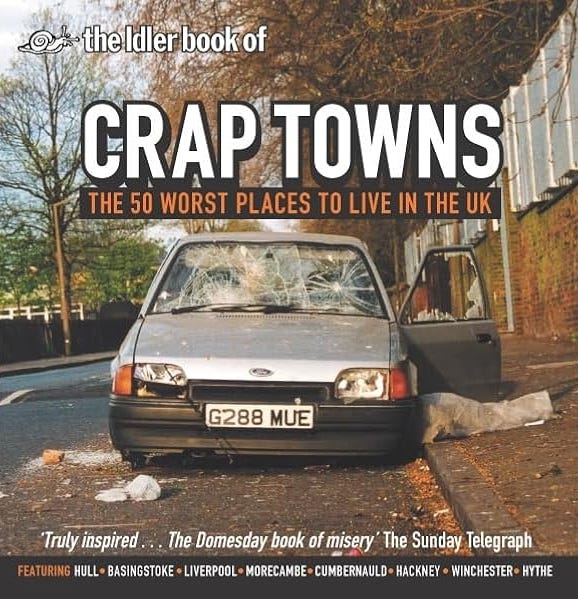

Last week, The Fence magazine ran an article about Crap Towns, a book series I started editing back around the turn of the millennium.

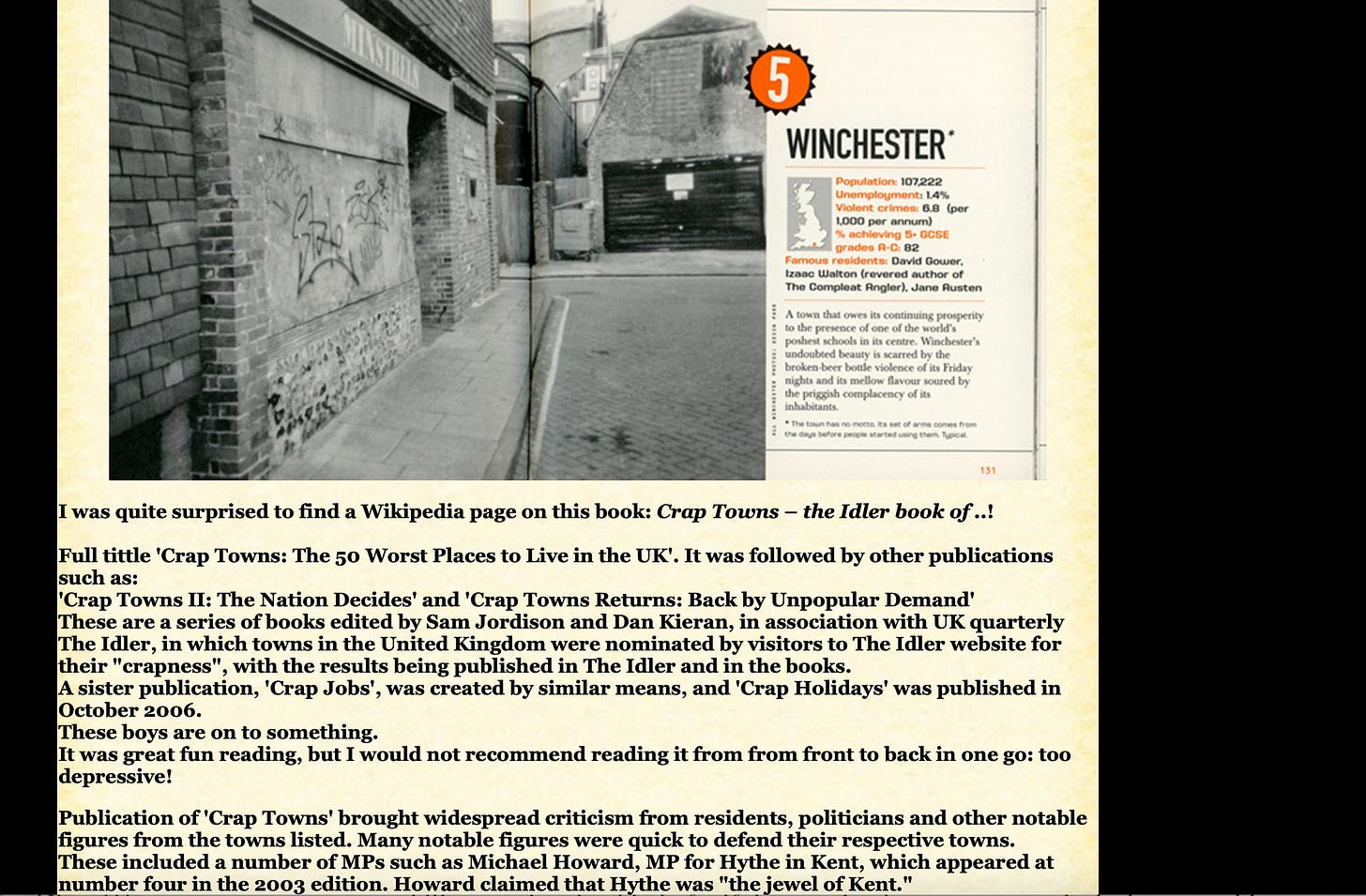

Crap Towns was about the worst places in the UK. It was a survey based on nominations from people who wrote into a website - along with a few bits of research, photography and micky-taking that I carried out myself. I hoped it would be a book about the true state of the nation – a ‘domesday book of misery’, as an early critic described it.

The Fence generously endorsed this idea by saying that Crap Towns was something that “struck at the real core values of British life: bodged buildings, massive class anxiety and rampant self-loathing.”

The author of the article, Adam Steiner, took Crap Towns in the spirit I’d always intended. He described it as an affectionate bit of chiding, an attempt to kick-start conversations about regeneration and how Britain could and should be better (as well as an excuse to have some fun with bad planning decisions, local corruption and car parks.)

It’s lovely to be talked about with such sympathy.

But there are complications. My thoughts about Crap Towns are conflicted for all kinds of reasons, but one of the most prominent is that it feels like a book from another age.

I was reminded of that problem when Adam brought up the question I am now asked about Crap Towns with the most frequency.

He wanted to know whether it would still be possible to publish this kind of book today.

And… well…

In the summer of 2021, when identitarian politics and all the related fear and loathing were close to their frenzied Covid peak, I took a call from another journalist who was writing a piece for the I paper about, as he put it, the “long rich tradition of various different UK towns being named the country’s worst.”

He was keen to talk to me as a “sort of founding father of the genre”. The fact that he thought of me as the progenitor of this absurd tradition was simultaneously great and disastrous for my ego. Should I be pleased? Should I be ashamed?

But it wasn’t that that knocked me sideways. Later on in the conversation, we got onto the current state of the nation and he said: “Of course, you wouldn’t get away with it now.”

Many of other people - plenty of them journalists - have said the same thing to me since, but this was the first.

It felt like something I had to contend with.

My first thought was: “Oh shit, there goes the twentieth anniversary edition.”

My next was (slightly) less self-involved. Instinctively, I knew that my interviewer was right. So what did that imply about modern Britain? And was it good or bad?

There was part of me wanted to rail against this change. I wanted to conclude that we’ve lost our talent for self-deprecation - and that this was something lamentable. We can’t take jokes any more!

But there was also another part of me that could see that I was yelling at clouds.

I realised that I was in danger of becoming just the kind of old fart that the younger version of me - the one who had come up with the idea of Crap Towns - might have enjoyed satirising. Which left me wondering - who was the asshole in that equation? Young me? Present me? Both of us?

Plus, much as I wanted to blame everyone else for their inability to take jokes about their hometowns on the chin, I could also see the problem:

Crap Towns was a book that blatantly and gleefully insulted everyone and everything. Maybe, just maybe, this big idea of mine had not been such a good one?

That Crap Towns was a bad book was definitely the opinion of some podcasters who put out an episode last year describing it as a “cursed object.”

They asked: “How did something so cursed - so unpleasant - end up as a national publishing sensation? Were our brains all fried by lads mags, New Labour and tabloid journalism?”

They answered those questions by explaining that the problem was that the books were meant to be humorous.

“They want people to laugh and I find that so unappealing,” said one of the presenters.

I could feel my head banging against the dustbin of history as she spoke.

But I have to admit I also find this kind of puritanical outrage pretty amusing. It’s one of life’s delicious ironies that people who don’t want to laugh are often inadvertently hilarious.

Even so, I also felt sad and worried listening to that podcast. It reflected a kind of strident and confident righteousness that I’m not sure has been good for the world - and I’m not sure will stand up to the scrutiny of time.

After all, if there is anything that ages even more badly than jokes, it’s moral certainties. I’m always reminded of poor old Miss Clack in Wilkie Collins’ Moonstone; so fervent in her belief that the moral tracts she insists on handing out are the final word in ethics, so gloriously unaware that Wilkie Collins was setting her up as a laughing stock.

And that’s not to mention the actual puritans.

Meanwhile, it’s rarely a good idea to silence the instinct to make jokes. We need scamps. They’re the ones who point out that the emperor isn’t wearing any clothes. Sometimes they’re also the ones that make unkind remarks about the size of his paunch. But I’d notch that up as the cost of allowing the kind of freedom that reveals true and important things.

The other thing about scamps is that they help us have fun. And that was definitely one of the intentions of Crap Towns.

But maybe that was easier twenty years ago? Maybe everything seemed more enjoyable when there was at least a hope of change? And when hope was actually something people might consider voting for? When the world felt safer and kinder?

I know that even back in 2003, not everyone enjoyed the joke. But I also remember that I wasn’t alone in wanting to make it. Thousands of people wrote into the website to share their own stories about the places they lived. Thousands of people bought the books. I like to hope that they enjoyed them too - and the fact that they became word-of-mouth bestsellers suggests that they might have.

I went on dozens of radio shows, TV programmes to talk about Crap Towns - and I don’t think I was ever asked what the hell I thought I was doing. Even when local papers from the towns on the list got in touch, the journalists tended to think it was pretty funny. They would tell me as much when we spoke, as well as fervently agreeing about the problems on their beat. True, they then went on to write outraged front pages about the dastardly things that were being said about their town – but they did so in a way that let everyone know they were in on the joke. We were all laughing at ourselves and each other.

It makes me feel pretty nostalgic - not least because if it is indeed true that we’ve lost the ability to enjoy that kind of self-deprecating humour, we may be losing something important, alongside the pleasure of laughter.

Because that laughter also brought a kind of freedom. It enabled us to speak truths that might otherwise have felt too uncomfortable.

And today, it can sometimes feel like all we’ve got left is the discomfort.

The good news is that I don’t think that the illiberalism of identity politics will endure much longer. Especially when it comes to the literal policing of humour - and cancellation of comedians for telling the wrong kinds of jokes.

But that doesn’t mean we aren’t still dealing with the repercussions. I can’t prove it, but I have a strong sense that there has been a nervousness about humour in the publishing industry for quite a few years.

After all, is it always worth taking on projects that might upset people like the presenters of that Cursed Object podcast? How many editors and writers have found themselves second guessing these kinds of reactions and steering clear as a result?

To give one small example. A few days ago I was fortunate enough to talk to the novelist Jonathan Coe about his latest (very enjoyable!) book The Proof Of My Innocence. One of the sections of this book is a pastiche of auto-fiction, written in the combined voices of two twenty-something women.

Even for a writer as established and successful as Jonathan Coe, inhabiting these different voices was brave. As he said to me, the contemporary climate would make anyone “nervous” about taking such a step. Writers are expected to stay in their lane. To do otherwise is to go against a lot of contemporary instincts.

The great thing about Jonathan Coe was that if he did indeed feel afraid, he did it anyway. Good job too because I thought the result was very funny and touchingly empathetic.

In fact, to be afraid and do it anyway is advice I’d want to give to most writers. I’d want to suggest that the fear and the sense of transgression might even be the things that make the end result interesting.

But it’s not advice I myself can take in the case of Crap Towns. I’m not going to try to write another for a while. Because I worry that the books still might not work.

There are, after all, only two kinds of joke: those that were once funny and those that were never funny.

Much as I’d like to, I can’t just blame the puritans if my old jokes don’t work any more. Nor can I claim that the Crap Towns books were an unqualified success, even taken on the generous terms that Adam Steiner set out in The Fence Magazine.

I mean: incredibly, governments and local councils didn’t read my work and decide to mend their ways. The UK did not get better. Instead we got more than a decade of Tory austerity, Brexit, and all the accompanying neglect and bad feeling.

The joke has gone sour.

I even worry that in trying to diagnose some of the alienation, boredom and despair that people in the UK were starting to feel, I actually might have added to the malaise.

Explaining everything that has gone wrong in the UK would take quite a few more articles like this one, so that’s probably enough for now. But before closing, I should admit that there is a more straightforward answer to the question of whether you can still get away with doing something like Crap Towns.

That answer is: yes.

There’s a website (I won’t link to it) that has kept on running a survey of the worst places in the UK for years and years- and, honestly, when I look at it, I hate it. Partly because I feel like they’re ripping off my project, but mainly because when I read the comments on there about incels and chavs and carbuncles and brutalism it all just seems grubby. Maybe even cruel.

I could argue that I don’t like this website because their approach and criteria are different to mine - and I hope there would be some truth in that. But I also know that I now also just react against the whole thing. It’s been done. It’s grown stale. It doesn’t fit - especially since so much has changed around it. In short, the world has moved on.

And maybe that’s not such a bad thing?

Fondly,

Sam

We’ve got a new Galley Beggar book on the way! Look out in our next newsletter for more on that.

As well as Jonathan Coe, Lori Feathers and I recently interviewed translator and poet Michael Hofmann on Across The Pond. He was wonderful - and the book we talked about, A Frog In the Throat by Markus Werner, is tremendous. Strong recommend.

The Galley Beggar Critical Reading class is about to start a new season. First book we’re reading together will be Erasure by Percival Everett. There’s still plenty of time to sign up and get reading.