Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

Well, this is awkward...

For months, many, most, if not all economists have been predicting a re-inflation due to the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration. They are not small increases but dramatic increases that shattered a 70-year postwar run of low tariffs. Every bit of economic theory would suggest that the new taxes paid on imports by American businesses and consumers would feed into price increases.

Those price increases keep not happening.

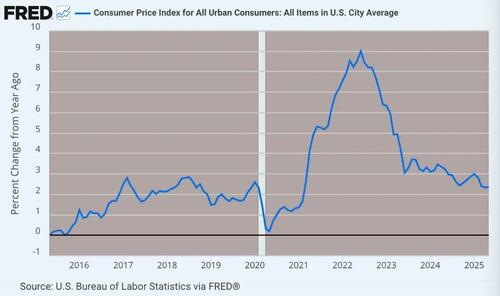

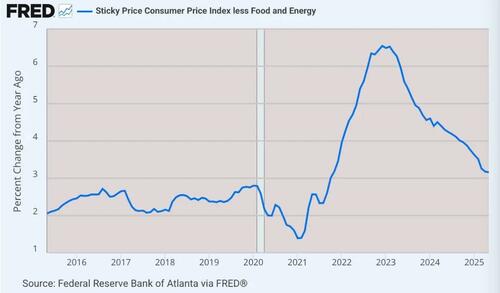

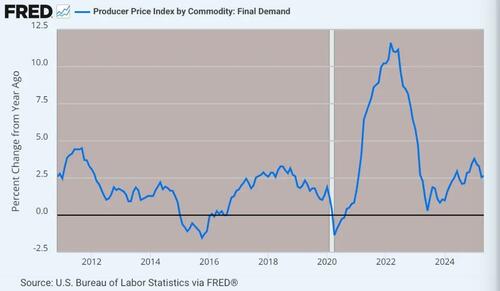

The consumer price index (CPI) and producer price index (PPI) data came out last week. They once again underscored the point. Inflation is not dead but it has hit new lows relative to what we’ve been through for four years. Tariffs seem not to have made any difference at all.

The CPI is running 2.37 percent year- over- year.

The sticky-price index is 3.15 percent year-over-year, which is high but at a post-lockdown low.

The PPI is 2.64 percent year-over-year, which is higher than the target but still a notable improvement.

Factoring out the annualization, the monthly trends look better than ever. Real-time inflation is running below 2 percent.

Incredibly, all of this began nearly to the day of Trump’s inauguration. I’m not naive enough to speculate a cause and effect here. To be sure, many of Trump’s executive orders are excellent for lower prices. His energy deregulation and product deregulation and simple loosening of the tethers on industry are deflationary. However, the sudden downward motion is more likely due to the reality that the previous inflation had been spent.

Money supply only recently hit levels it was at three years ago, having bowed downwards. The dramatic high interest rates by the Fed clearly sopped up vast amounts of liquidity from the system. The Biden-era spending binge is all spent. Trillions of dollars were vacuumed out of the purchasing power of the dollar, such that the 2025 dollar is worth a quarter less than it was five years ago.

That tragedy happened and it was terribly painful. But it is over for the most part. I count this as the most fortuitous coincidence of events for the Trump administration. The president can take all the credit even to the extent that it might not be deserved.

That’s fine. That’s politics.

But many people did worry that the tariff imposition would give inflation a second wind. That has not happened, so far, which is something of a shock. Many economists are now saying that it is coming. That makes sense according to theory but even I am having my doubts.

Tariffs are a hot potato that someone has to hold. It’s going to be domestic consumers, domestic businesses, or suppliers who will pay in the form of price adjustments. The revenue does not appear automatically. Someone has to pay.

For now, it does not seem to be either producers or consumers. So far as we can tell. Again, this is for now. And it may yet happen. No one can say for sure.

All of which serves as an excellent reminder of a core point about economics that everyone wants to forget.

It is this. Economics can make predictions but not quantitative ones. It is notoriously terrible at naming numbers and dates. Forecasters who get it right once are nearly guaranteed to get it wrong the next time. The rare forecasters who get it right two or three times is mega-guaranteed to be spectacularly wrong on the fourth or fifth prediction.

Economics is excellent at making qualitative predictions. This amounts to observing that X will cause Y provided that Z remains constant. That is true so far as it goes. But Z is never constant. For that reason, economics cannot make quantitative predictions with any degree of reliability.

That is true now and has always been true.

The trouble is that this observation—simple and unobjectionable by any normal human intellect—flies in the face of what economics has been trying to do as a profession for the better part of 100 years.

The motto of most economic schools of thought is that science is prediction. The better the prediction, the closer we come to real science. Economics has been chasing this rainbow for a century but never finding the pot of gold at the end of it.

This outlook represents the height of intellectual arrogance. At its root, real economics is about human choice. Human choice defies prediction. Ergo, economics cannot be about quantitative prediction. Its predictive power is always limited to qualitative realms. Going beyond that risks having economic science itself discredited as a fake science, which is how it is mostly seen today.

Still, economists just cannot help themselves. They gain too much in prestige and career advancement by pretending to have a crystal ball that all human experience has shown not to exist. So they just keep trying. And that means that they keep discrediting themselves.

To be sure, the economists are quantitatively correct. Tariffs raise prices in some area and for some group but it is not entirely predictable precisely who that will be. So far it appears not to be consumers.

There is also a point to make here concerning inflation and its definition. A new tax can raise prices but that is not the same as inflation, which, as Milton Friedman never tired of saying and proving, is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. Higher inflation means the depreciation of the currency, not merely an increase in the price of particular goods and services.

I’m not a fan of tariffs but let’s please stay objective about the empirical case: there is no evidence yet that Trump’s tariffs have increased prices. They appear, so far, to be eaten mostly by importers and not passed on or perhaps they are absorbed by exporters themselves who had high enough margins to pay the tariffs in the form of lower prices to make up the difference of higher fees to importers.

We don’t have enough empirical data to explain it all just yet. Still, if we are keeping score here, the economists who predicted impending doom by the end of low tariffs are not on the winning side. So far. And there is a lesson here: maybe economists could use a dose of humility.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

Loading...