Last time, we talked about Perl as an influence on Ruby, this time, we’ll talk about the other major influence on Ruby: Smalltalk.

Smalltalk had a different kind of influence, since almost nothing of Smalltalk’s syntax made into Ruby. But many of the details of how objects work are directly inspired by Smalltalk, including the idea that every piece of data is part of the object system.

Also unlike Perl, I spent a good couple of years working in Smalltalk, and it is one of my favorite languages that I’ll never likely use in anger again.

(A Personal) History of Smalltalk

Smalltalk originated in the same Xerox PARC team that invented the windowed interface, ethernet, and the laser printer, and who knows what else, they may have invented ice cream and rainbows.

There’s a whole story about what project Smalltalk was invented to be a part of, and a whole alternate history of computing and how people interact with computers that we are going to largely ignore. (If you are interested, start by searching for “Alan Kay Dynabook”.)

Smalltalk went through a few different iterations in the 1970s, but the version that we know today is a direct descendent of Smalltalk-80, which was the first version released to the wider world.

For most of the 80s and 90s, Smalltalk was something that doesn’t really exist today – a programming language and environment that companies paid money to use. Lots of money. The major player was ParcPlace, which was a spinoff of Xerox that provided Smalltalk tools. Their commercial product was originally called ObjectWorks, later changed to VisualWorks, and eventually sold off and presumably slowly losing customers after the late 90s.

Smalltalk was pretty big in the industry for a while. Most of the aviation industry ran on it in the 90s, the big payroll project that was the basis for Extreme Programming was a Smalltalk project, there was reasonably high demand for Smalltalk programmers through at least the mid 1990s. I taught an undergrad OO class in Smalltalk in 1997 and 1998 to students that wanted to be learning C++, and I remember telling them that Smalltalk programmers were paid more.

I first encountered Smalltalk as a grad student in about 1993, where Georgia Tech used ObjectWorks to teach Smalltalk and Object-Oriented programming (there’s a whole other sidebar about how Object-Oriented languages came to prominence in the 90s, and the arguments over that but again, another day). ObjectWorks was pricey, and there was also a lower-cost vendor called Digitalk, and eventually I also used a product called Smalltalk Agents, which has apparently totally vanished from the entire internet.

In 1995, a bunch of the original Xerox Smalltalk team was together at Apple, and they decided to release an open-source Smalltalk VM. What they did was very interesting. They wrote a very, very small kernel in very vanilla C, and then 95% of the environment was then built in Smalltalk on top of that. Oh, and even the vanilla C was written in Smalltalk, they wrote a Smalltalk to C compiler. They called their new Smalltalk “Squeak”, which made a lot more sense when they all moved en masse to Disney.

The fact that Squeak was largely written in itself made it fairly easy to port to new systems, and it was quickly available on just about anything with a microchip.

I’m pretty sure that I first saw Squeak at the OOPSLA conference in 1997. (Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages & Applications, since you asked) At this conference I somehow got to do a team-building exercise with Adelde Goldberg from the original Xerox PARC team, which is not relevant to anything but seemed very cool at the time. I was already using Smalltalk in my projects, but Squeak was immediately interesting and my extended research team started doing cool stuff. Like, what I’m pretty sure was the first Wiki tool outside the original C2 Wiki, was written in Squeak. (Apparently at least one is still running).

Smalltalk’s Environment

It’s important to understand that Smalltalk’s development is a different evolutionary tree from nearly every currently popular programming language, in that Smalltalk is in no way, shape, or form influenced by Unix or C. Perl, Ruby, Python, JavaScript, Swift, Kotlin and on and on, all come from a universe where they expect to run Unix libraries, and where C syntax is normal. The Unix philosophy of “small pieces, loosely joined” is not a part of Smalltalk’s DNA at all.

Smalltalk is basically its own operating system, and the syntax is different from C-style languages in ways big and small. For example, the first element of an array is… 1. Which, when you think about how people count, actually makes sense.

It’s hard to separate Smalltalk the language from Smalltalk the environment, although I suppose technically you could have the language without the whole shebang (and I think there was a GNU Smalltalk that tried this), really the environment is part of the appeal.

Your main interfaces to the smalltalk system are a Workspace and a Browser. A workspace is analogous to REPL session, you can type in arbitrary Smalltalk code and have the system “do it” to execute the code, “print it” to execute the code and output the result. There are some other actions like “debug it” or “inspect it”, but that’s the basic idea. Unlike a Unix REPL, there’s no prompt, and you don’t automatically invoke code by hitting return, you have to select code and then invoke the menu item or the keyboard shortcut for the code you want to act on.

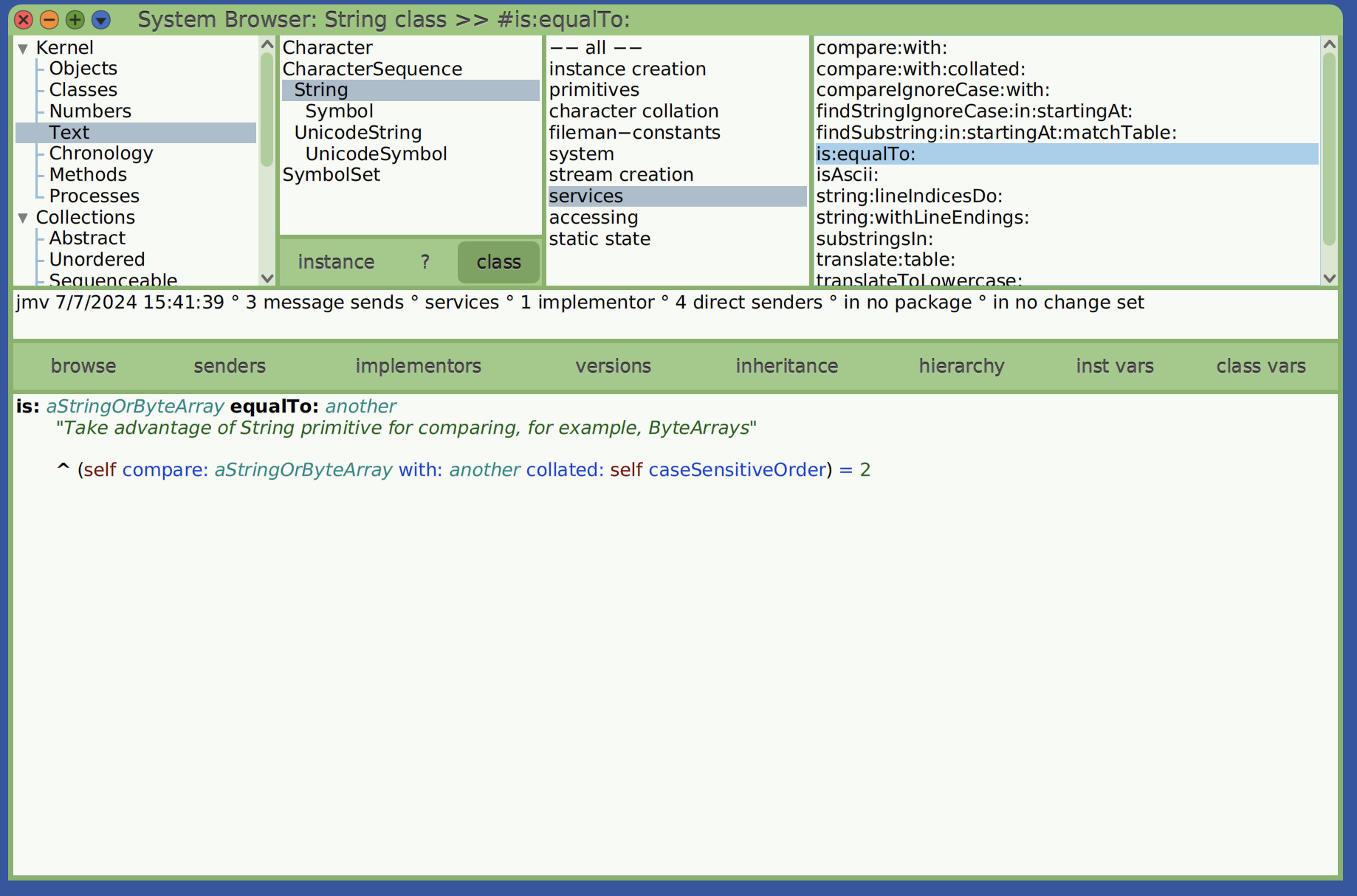

The Browser is where you write code. There a a few different versions in most Smalltalks, here’s the main one, this is from a modern Smalltalk called Cuis.

At the top, we have four window panes – left to right we have:

- Categories – groups of classes that are related in some way. Cuis nicely puts each group in a pulldown list. Categories have no particular syntactic meaning, they are just there to make browsing easier.

- Classes – one entry for each class in the currently selected category, at the bottom of this pane is a toggle for “class” vs. “instance” which determines what kinds of messages are shown in the next two panes.

- Protocols – a protocol is a user-defined group of messages. Smalltalk internally uses “message” rather than “method” because of how Alan Kay thinks about objects. Again, protocols are for the programmer, not the system.

- Messages – each messages in the currently selected protocol is listed.

The bottom pane is the code editor, and if a message is selected in the code pane, its code is displayed there.

You probably have questions:

Does this mean that you can see the source code for the entire Smalltalk system?

Yes, yes it does.

**Can you modify any code in the system? **

Yes, yes you can.

Even, like, deep system code?

Yes.

Isn’t that dangerous?

As a Ruby developer, you should know that it’s only as dangerous as the developers who use it.

How do you edit a message?

Just display the existing message in the browser, edit the message and select “save”. The Smalltalk system will parse the code, stop if there are syntax errors, but if not, the updated method will be saved to the system. A side effect is you can’t save code that isn’t syntactically parsable, even as a draft.

Okay, but how do you create a message?

The “real” way is to select a protocol but not a message, and Smalltalk will put a template in the edit window. Write your message in the editor and save it. Alternately, you can just change the name of a message in the edit window, and a new method with that name will be created, without deleting the old message.

And how do you create a class?

Similarly.

If you select a category and not a class, you’ll get this in the code editor pane:

Object subclass: #NameOfSubclass

instanceVariableNames: ''

classVariableNames: ''

poolDictionaries: ''

category: 'Kernel-Chronology'

The thing to note is that this is not actually template, it’s actually code: a message, waiting for you to fill in the arguments, replacing #NameOfSubclass and adding the instance variables and so on. You don’t save this, you “do it”, just like if you were in a workspace. The message call is evaluated, and Smalltalk creates a new class.

But wait, if all the code is in the image and isn’t in text files, how do people work together and share code?

Don’t worry about it.

Seriously, though, worry about it.

This has always been a problem. Smalltalk allows you to share “change sets”, effectively the code differences between one point and another. Classically, one person would export their change set, and other team members would import it. Different Smalltalks have built up more sophisticated tools over time.

Smalltalk’s Syntax

Smalltalk’s syntax is very simple, relative to Ruby and Perl.

Wait a sec, I literally wrote this for a chapter in a book about Smalltalk literally 25 years ago, here’s a slight paraphrase:

Every line of Smalltalk is evaluated the same way.

-

Every variable is an object. There are no basic types that are not objects.

-

Every expression is a message being passed to an object, there is basically no expression syntax that is not a message.

-

All messages return a value. (The return value is specified by

^, if the method does not specify a return value, it implicitly returnsself, the instance that received the message.) -

There are three kinds of messages:

- Unary messages like

3 negated - Binary messages like

a + b, these actually are messages you can define, there is a small set of them, and they are special cases in the parser. - Keyword messages such as

anArray at: 3 put: 7. This syntax got used by ObjectiveC and later Swift, so you may be familiar with it. It’sreceiver <messagepart>: <argument>where you can have multiple message parts. If you are referring to the message, typically you just say the message parts, so this message would be calledat:put:

- Unary messages like

-

Smalltalk does not have operator precedence. All code is evaluated strictly from left to right. Unary messages first, binary messages second, keyword messages last. Parenthesis can be used to force order of operations or to make things clearer.

-

The assignment operator is

:=(Smalltalk uses=for boolean equality), the right hand side is evaluated and the value is assigned to the result of the left hand side.

And that’s basically it, with a couple of ways to create literals like strings, arrays, dictionaries, local variables, and blocks.

So, for 10 points and control of the board, what does this do?

hypotenuse := 3 squared + 4 squared sqrt

The unary messages are evaluated first:

hypotenuse := 9 + 16 sqrt

There’s still a unary message

hypotenuse := 9 + 4

Now we can do the binary message:

hypotenuse = 13

Oops.

To get what you actually want, you need parentheses:

hypotenuse := (3 squared + 4 squared) sqrt

Smalltalk does not have special syntax for loops, all loop behavior is defined by methods on Array and the like, very similar to Ruby’s Enumerable.

Smalltalk does not have special syntax to create messages or classes. Message creation is managed by the editor (which internally calls a message that adds the new code), class creation is just another method – in Squeak, that method is Object#subclass:instanceVariableNames:classVariableNames:poolDictionaries:category:.

Smalltalk does not have special syntax for boolean logic, all logic behavior is defined by the classes True and False. Ruby sort of does this, but Ruby does have if as special syntax. Smalltalk does not, you’d write a Smalltalk conditional as just another message:

(x > 10) ifTrue: [ x squared ] ifFalse: [ x sqrt ]

The square brackets are blocks, and behave very similar to Ruby blocks, except that you can treat them as just normal variables and normal arguments. You can even, as in this case, have multiple arguments that take blocks.

The implementation if the method ifTrue:ifFalse is simple. For the True class, it just takes the true block and executes it by passing it the message value.

ifTrue: trueAlternativeBlock ifFalse: falseAlternativeBlock

^trueAlternativeBlock value

And for the false class, the exact opposite:

ifTrue: trueAlternativeBlock ifFalse: falseAlternativeBlock

^falseAlternativeBlock value

Smalltalk doesn’t have a case or switch statement, typically if you want behavior like that you’d define a dictionary of keys to blocks or you would use the object system and polymorphism and double dispatch.

Smalltalk’s Object Model

There’s a lot about Smalltalk’s object model that sound familiar to a Ruby developer:

- There’s a base class called

Objectthat everything inherits from. - Instance variables are private. Getters and setters default to having the same name as the instance variable.

- Method lookup happens at the point of the method call.

- Classes are instances of the class

Class(sort of). - There’s a thing called a “Metaclass”

- There’s a method that’s the method of last resort – in Ruby, it’s

method_missing, but in Smalltalk it’s calleddoesNotUnderstand

There are a couple of differences as well

- Smalltalk’s meta classes are structured differently, I explained this once and I’m not sure I ever want to explain it again.

- Smalltalk doesn’t have multiple inheritance or mixins or modules or anything like that. Although there have been some attempts to add these features, the traditional Smalltalk way to do this is through delegation.

But overall, Smalltalk and Ruby are similar enough that a huge amount of Kent Beck’s Smalltalk Best Practice Patterns is applicable to Ruby as long as you translate the syntax.

What Happened?

Unlike Perl, I actually did use Smallalk to build a few real applications that had real users. I miss it a lot.

I find that when I try to explain Smalltalk to people, it’s easy to explain the syntax and the object model. What’s hard to explain is how it is to work in a Smalltalk environment.

You’ve likely used powerful coding editors and terminals. Smalltalk is just different. You are in the running environment.

- Tests start instantly, and in general run very fast. There’s a dedicated test runner window. Some smalltalk integrate tests with the regular browser, so you can see test status from the code browsers.

- Debugging is amazing, you can investigate the state of any object in the system, you can change that state, you can easily execute arbitrary code. You can have a test halt on exception, update the code and re-run from the point failure. It’s hard to describe how fluid it is, especially since I’m no longer expert enough to do it fluently.

- While the editor doesn’t have all the niceties of the IDE’s you are used to, it’s very powerful in its own way. If you save code with a message name that does not appear in the image at all, Smalltalk will typically ask you if you want to define it right there. A lot of the things we ask a Language Server to do, Smalltalk just kind of does, because the image has access to everything.

But the all-encompassing nature of the environment was also Smalltalk’s downfall. As more and more of the general computing environment became Unix and the “small pieces loosely joined” philosophy, Smalltalk got harder and harder to integrate. Smalltalk isn’t a scripting language, it was late to develop connectivity to external databases, its model of team interaction is fundamentally different from Unix source control. The image-based system has some drawbacks – you do get amazing access to the system, but it can be hard to tell where your code ends and the system begins. Code could depend on the state of the image in ways that were hard to replicate in deploys.

What Did Ruby Take From Smalltalk?

Smalltalk’s legacy in Ruby is primarily the object model – the idea that everything is an object and everything is manageable via method calls, and that message calls are evaluated at the point of call, as late as possible. Ruby takes that idea and translates it into a syntax that is more familiar to programmers used to C/Perl/Java.

I’m not sure this is exactly on point as far as Smalltalk’s influence on Ruby, but my Ruby style has always been very aggressive about creating new classes and objects. I’m quite confident that a reason for that style is that I came from Smalltalk first and not Java, Smalltalk style is much more amenable to small classes.

On my first largish Smalltalk project, users were simulating a chemical plant’s pipe system by placing tiles with pipes in them, and I frequently needed to do logic based on relative directions. I clearly remember creating a Direction class with basically four live instances, up, down, left, right, and just enough logic inside to say that up.turn_left equals left, but down.turn_left equals right. It was useful enough that I remember how much fun it was to build it even now, nearly thirty years later.

Of all the other programming languages I’ve used, Ruby is the one that most clearly encourages that style of coding.