"Subsystem" on Windows NT has a vague definition. It basically means an API set, but predominantly for supporting programs written for other operating systems mostly through lightweight call translations. Windows NT, formerly "NT OS/2", used to have an OS/2 subsystem that supported running OS/2 applications just by translating API calls to NT.

Subsystems usually have a separate process for state bookkeeping. There used to be an OS/2 subsystem (OS2SS.EXE), but there were more. Even Windows is a subsystem on NT architecture. The enigmatic CSRSS.EXE is the Win32 API translation layer for Windows NT. You can see the pattern: the "SS" stands for "subsystem". Because of its performance problems, some portions of CSRSS were ported to kernel mode and were called WIN32K.SYS.

There was also a long-lived, pretty much useless POSIX subsystem (PSXSS.EXE) on NT. It was mostly to sell NT to the government because they required operating systems to be at least POSIX.1 certified. It implemented the bare minimum POSIX API to get the certification, and nothing else.

POSIX subsystem was later replaced by a more complete Windows Services for Unix developed by Interix, based on OpenBSD API. Unlike other subsystems, it was not binary compatible with any Unix, but provided its own API set and tooling, so apps could be compiled for it.

Enter WSL1

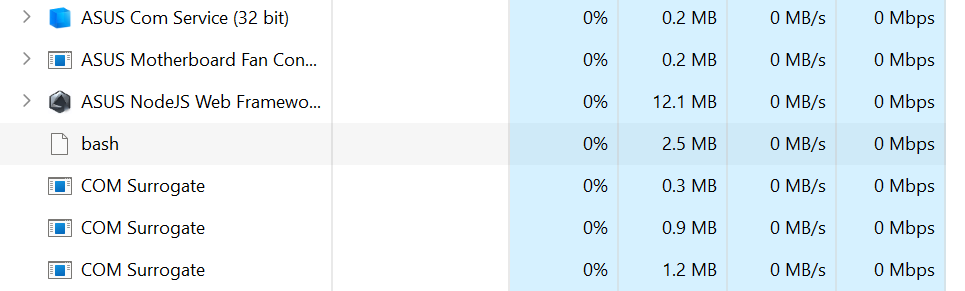

WSL1 is the first incarnation of Windows Subsystem for Linux. I think the name is silly though because we all know that the actual Windows subsystem for Linux is Wine. I wish Microsoft had kept its initial name: LXSS. Anyway, WSL1 is a thin translation layer like the subsystems I mentioned. When you run bash on WSL1, it only allocates a few MBs of memory just what bash needs, and that's it. You could see and manage bash process in Task Manager along with other Windows processes:

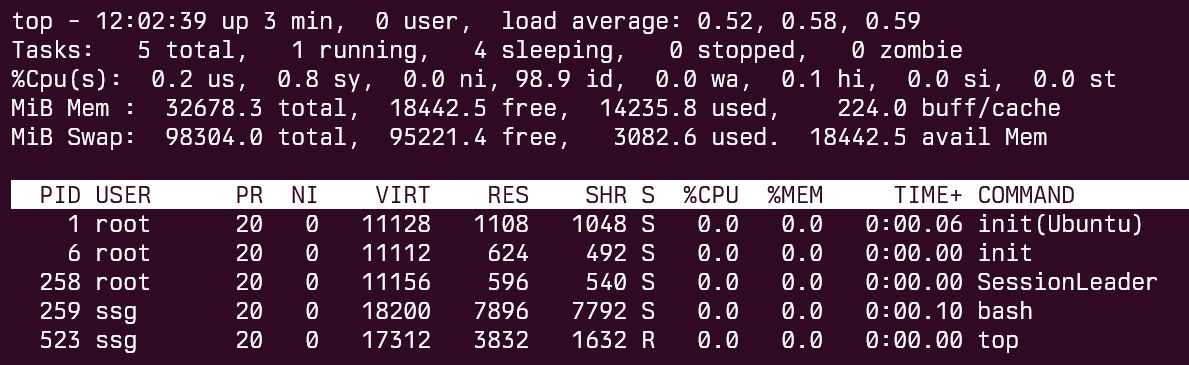

This is the full process list that shows up on top:

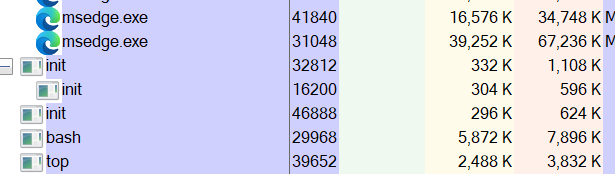

Okay. bash allocates only how much it would allocate on a Linux machine, but isn't there still a runtime cost somewhere? We see at least init here in the list. When we open up the process list in Sysinternals Process Explorer, it shows up in a process tree:

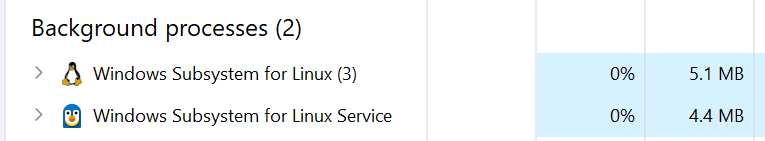

init is there but what else? When I search WSL in Task Manager a few services show up:

Is that it? If I'm not missing anything, that's the overhead of having Linux on your system using WSL1. Only a few megabytes.

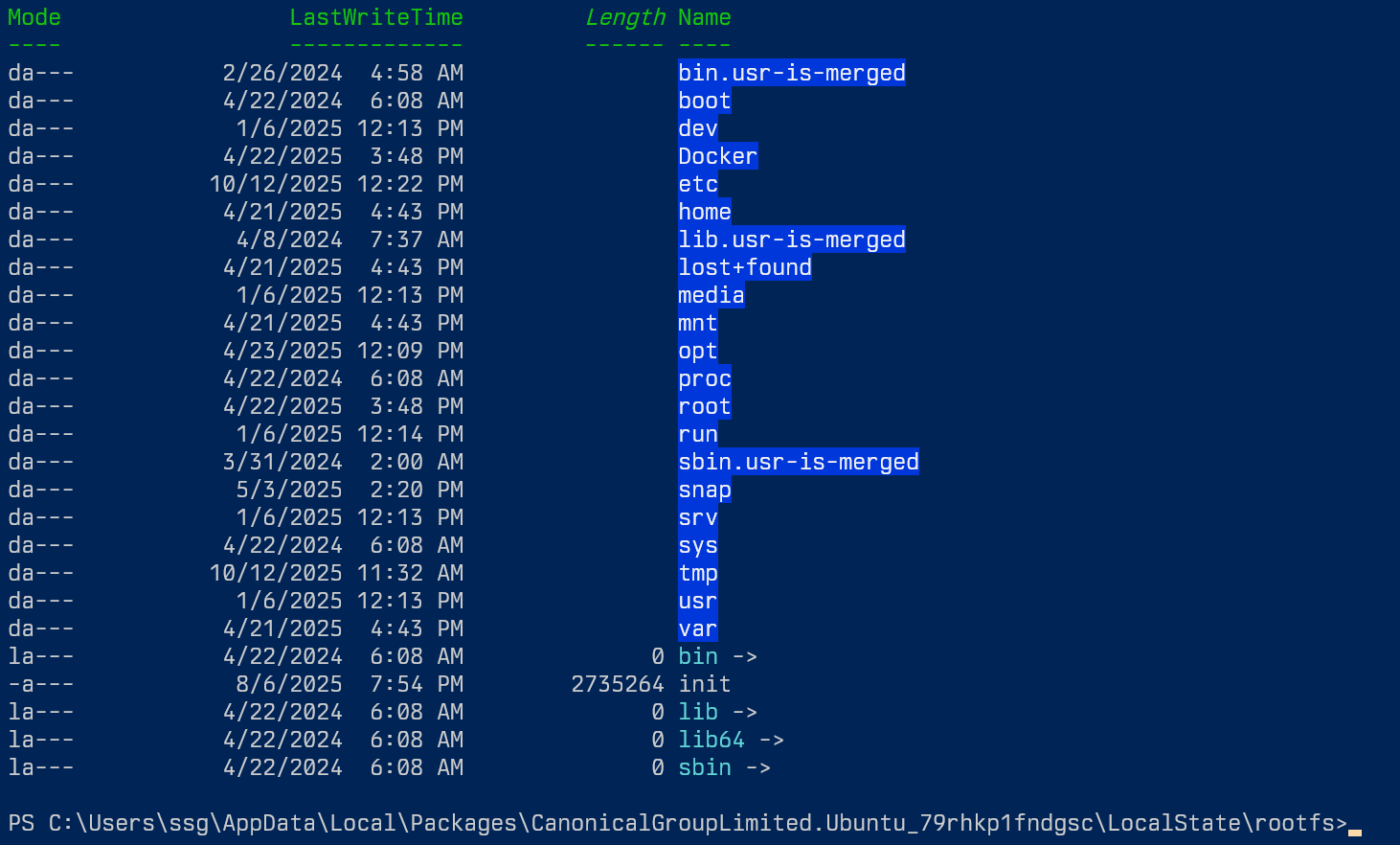

The root filesystem of WSL1 also resides on your NTFS partition. Every file exists on the disk separately. This means that the storage overhead could be minimal because adding new files wouldn't require to expand an image file.

Downsides of WSL1

WSL1 was a technical marvel, but it suffered serious performance problems on certain I/O heavy scenarios because Linux and Win32 filesystem APIs were too different, and translating them made some apps and some workflows seriously suffer.

There were other limitations with WSL1 too. It required you to install a third-party X Server on Windows to run GUI apps. I myself had used X410 for that purpose. WSL1 also lacked support for raw socket operations because Windows API had restricted them after the Blaster worm incident. So, even traceroute wouldn't run, let alone other raw packet tools like nmap or tcpdump.

Enter WSL2

People rightfully complained because they wanted to use Windows for workflows that needed similar performance characteristics as a native Linux system. So, Microsoft threw the towel and ended up creating a full-blown Linux VM on top of Hyper-V.

Because it's a VM and it works with a native Linux filesystem, the whole root filesystem of Linux stays in a single VHDX file. One of the great things about WSL is that you can convert your installations between WSL1 and WSL2 back and forth with a command like:

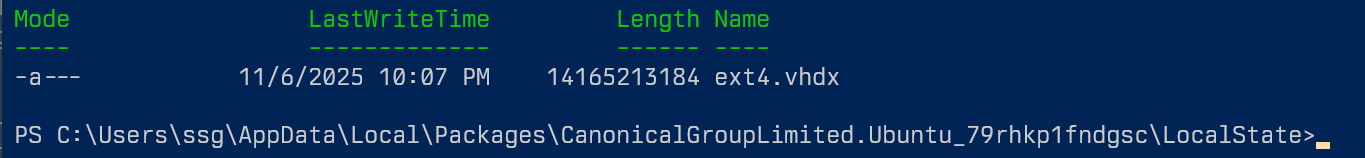

wsl --set-version "Ubuntu" 2Conversion might take a while though as all your files from your root FS are moved from NTFS to a VHDX file or vice versa. Here's my installation after the conversion to WSL2:

You can also have multiple Ubuntu setups, one with WSL1 one with WSL2 and use them interchangeably depending on your needs. Both are supported with different tradeoffs.

WSL2 is faster in certain workflows but it's slower to start initially because of the whole booting up the VM thing. As a reward, you're running a real Linux kernel now:

$ uname -a

Linux SSGHOME3 6.6.87.2-microsoft-standard-WSL2 #1 SMP PREEMPT_DYNAMIC Thu Jun 5 18:30:46 UTC 2025 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/LinuxThat kernel is provided by Microsoft with many options tuned for WSL2 environment. You can compile your own kernel and run it with WSL2 too if you want. I had to do that once when I needed to access an SD card from my WSL2 setup. They were disabled on default WSL2 kernel at the time.

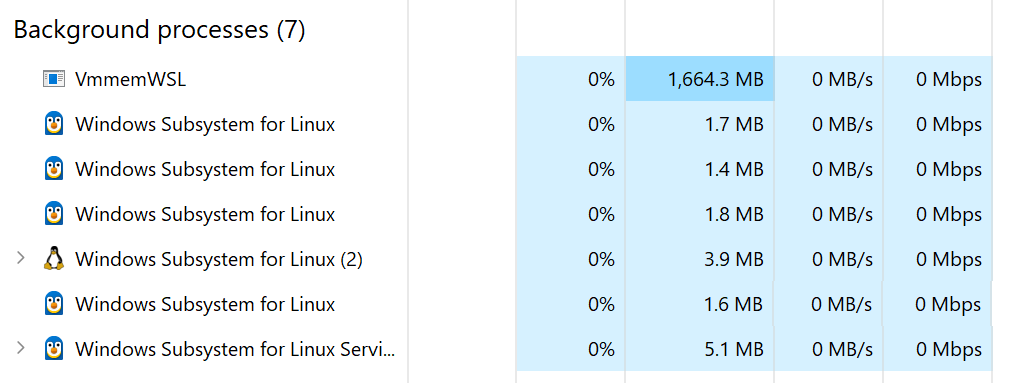

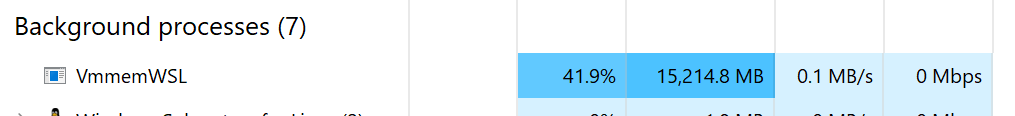

WSL2 starts up fast enough though, like it takes maybe a second, but still a difference you experience after every reboot. After you start your initial WSL2 session, you now have a perpetually running VM on your system. Luckily though, it doesn't consume as much as memory when idle. This is what it looks like with a single bash prompt:

1.6GB on a 32GB system. Does that mean we only have a 1.6GB RAM VM? No. WSL is smart about this. It claims to allow half my physical memory, 16GB:

$ cat /proc/meminfo

MemTotal: 16324732 kB

MemFree: 15077248 kB

MemAvailable: 15547632 kBSo, I expect the memory usage of VmmemWSL process to grow when you run Linux apps with greater memory requirements. I assume that it probably shrinks back when it needs less memory. So, it's quite good. It's not even enough to malloc the memory, the processes need to commit to it. Otherwise, memory usage doesn't grow at all. Here is a test using the tool stress:

$ stress --vm 16 --vm-bytes 1000000000

stress: info: [1793] dispatching hogs: 0 cpu, 0 io, 16 vm, 0 hddThat immediately maxes out the memory usage of WSL2, and eventually crashes because available memory is less than 16GB (more like 15GB):

When you kill the app it shrinks back to its original footprint in 10 seconds or so:

I think that's pretty much okay. What'a a gigabyte to spare in these days anyway? Just assume that you're running your clock app under Electron. If you really need the full memory to yourself, you can always shutdown WSL2 from a Windows Command Prompt, and it will start automatically the next time you need it:

wsl --shutdownNot too bad. I think the RAM overhead of WSL2 is okay based on the benefits it provides.

Is a VM really an NT subsystem?

First, Microsoft calls WSL2 a subsystem, so I guess it must be. But, based on our definition around API translation layers for ABI imitation, it isn't a subsystem. It's a VM.

32-bit Windows versions used to have an NTVDM (NT Virtual DOS Machine) layer to run DOS and 16-bit Windows applications. It basically worked pretty much similar to WSL2. It wasn't called a "VDMSS.EXE" or so at the time because it didn't fit the definition of a subsystem, but it acted more like a virtual machine, more like WSL2.

However, WSL2 isn't a stock VM either. As I mentioned before, it dynamically allocates memory and shrinks it as needed, it mounts your Windows drives, and lets you access your Linux drives as network shares using \\wsl$\ path syntax, it integrates almost seamlessly with desktop using a layer called WSLg. I say "almost" because every Linux GUI app we're running is actually a Remote Desktop client streaming that app from Linux VM to our Windows machines. It's still great though, apart from not being aware of my desktop settings like text scaling, HiDPI, and whatever. You need to set those up from scratch on your Linux environment.

Downsides of WSL2

My biggest issue with WSL2 is file management. Naturally, WSL2 feels at home when you do all your work on its ext4 image, but your work stays in the image then. An approximately 16GB single file called ext4.vhdx hidden deep inside your hard drive. I don't even know what happens if you uninstall Ubuntu or decide to switch to a different distro. Do you move your files manually between two distros using scp or something like that? I don't like that kind of fragility about keeping your work inside a big disk image.

Okay, I checked it now, and if you run wsl --uninstall Distro your image remains, but if you run wsl --unregister Distro all your files, all that you've worked on are gone in a second. Those two commands are dangerously and Levenshteinly close to each other.

You can use your Windows drives for your work of course. They're automatically mounted anyway, your drive C: is at /mnt/c for example. But, their performance is even worse than WSL1 on NTFS because now both VM overhead and syscall overhead take effect together.

I had been converting my WSL setup between WSL1 and WSL2 while writing this article. I noticed that WSL1 was using drvfs while WSL2 was using 9p protocol, which is Plan9's remote file system protocol. I find the idea of a piece of Plan9 from Bell Labs running on my Windows box quite fantastic to be honest.

I think I found a bug with the conversion process though. When I converted WSL1 distro back to WSL2 again, drvfs mount entries stayed as is, and were not replaced with their 9p counterparts. I got stuck with drvfs, I didn't want to bother with fixing it and just deleted and reinstalled Ubuntu. It's that easy. That's why it would make me uneasy to keep my work in a disk image.

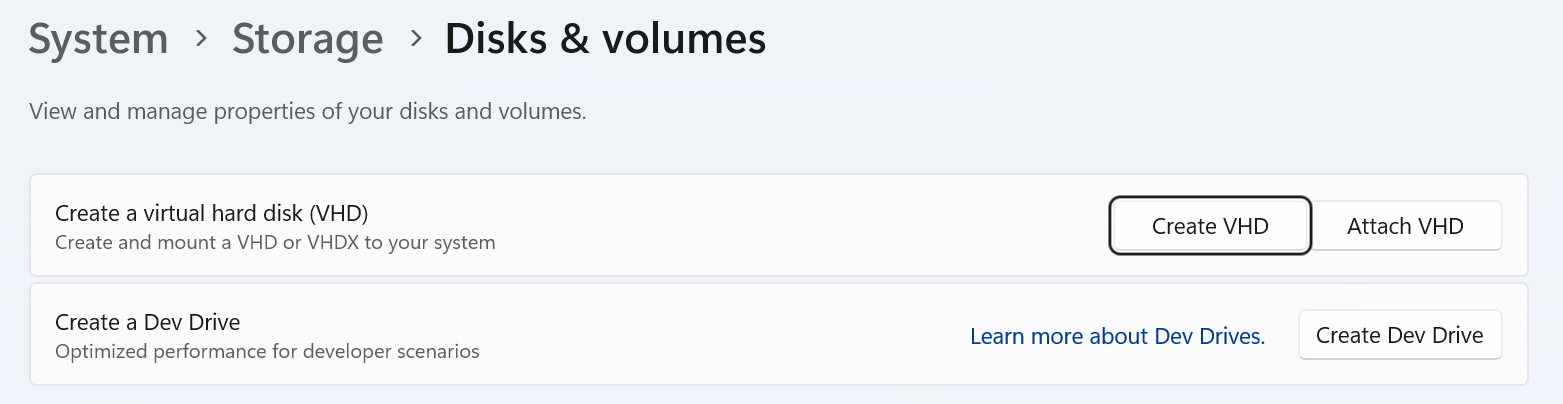

All in all, unless I always remain synced with a remote repository or have backups in place, I'd refrain from doing serious work on an WSL2 root partition. A good middle ground is to use a separate disk image for your work. You can create VHDX images directly from Windows settings:

And you can mount it with wsl --mount --vhd. I strongly recommend that for any serious work. Unfortunately, you can't specify VHDX mounting options in .wslconfig, so you'll have to create wrapper scripts to launch WSL. I wish it were easier.

I might be biased as a former Windows engineer, but I love Windows NT's modular design. I love that I can load a binary-only device driver from 15 years ago on my system and use a legacy device easily on a modern system; a stable kernel ABI goes a long way (hence the saying "Win32 is the only stable ABI for Linux"). Having OS subsystems incorporated into the design from day one is just a cherry on top.

WSL1 has great advantages like extremely lightweight memory overhead if you can bear its limitations. But, WSL2 is no slouch either. It can dynamically grow and shrink back to a gigabyte if you have that to reserve. Or, you can always shut it down if you need more memory.

WSL2 spends good amount of effort to work around the problems of a VM such as heavy memory footprint or lack of integrations with the host OS. I think it would be fair to call it a subsystem, just to separate it from heavyweight VMs.