Written by me, proof-read by an LLM.

Details at end.

Who among us hasn’t looked at a number and wondered, “How many one bits are in there?” No? Just me then?

Actually, this “population count” operation can be pretty useful in some cases like data compression algorithms, cryptography, chess, error correction, and sparse matrix representations. How might one write some simple C to return the number of one bits in an unsigned 64 bit value?

One way might be to loop 64 times, checking each bit and adding one if set. Or, equivalently, shifting that bit down and adding it to a running count: sometimes the population count operation is referred to as a “horizontal add” as you’re adding all the 64 bits of the value together, horizontally. There are “divide and conquer” approaches too, see the amazing Stanford Bit Twiddling Hacks page for a big list.

My favourite way is to loop while the value is non-zero, and use a cute trick to “clear the bottom set bit”. The loop count is then the number of set bits. How do you clear the bottom set bit? You and a value with itself decremented!

value : 11010100

subtract 1 : 11010011

& value : 11010000

If you try some examples on paper, you’ll see that subtracting one always moves the bottom set bit down by one place, setting all the bits from there down. Everything else is left the same. Then when you and, the bottom set bit is guaranteed to be and-ed with zero, but everything else remains. Great stuff!

All right, let’s see what the compiler makes of this:

The core loop is pretty much what we’d expect, using the lea trick to get value - 1, anding and counting:

.L3:

lea rax, [rdi-1] ; rax = value - 1

add edx, 1 ; ++result

and rdi, rax ; value &= value - 1

jne .L3 ; ...while (value)

Great stuff, but we can do better. By default gcc and clang both target some kind of “generic” processor which influences which instructions they can use. We’re compiling for Intel here, and gcc’s default is somewhere around Intel’s “nocona” architecture, from 2004. Unless you are running vintage hardware you can probably change it to something better. Let’s pick the super up-to-date “westmere” (from 2010…) using -march=westmere and see what happens:

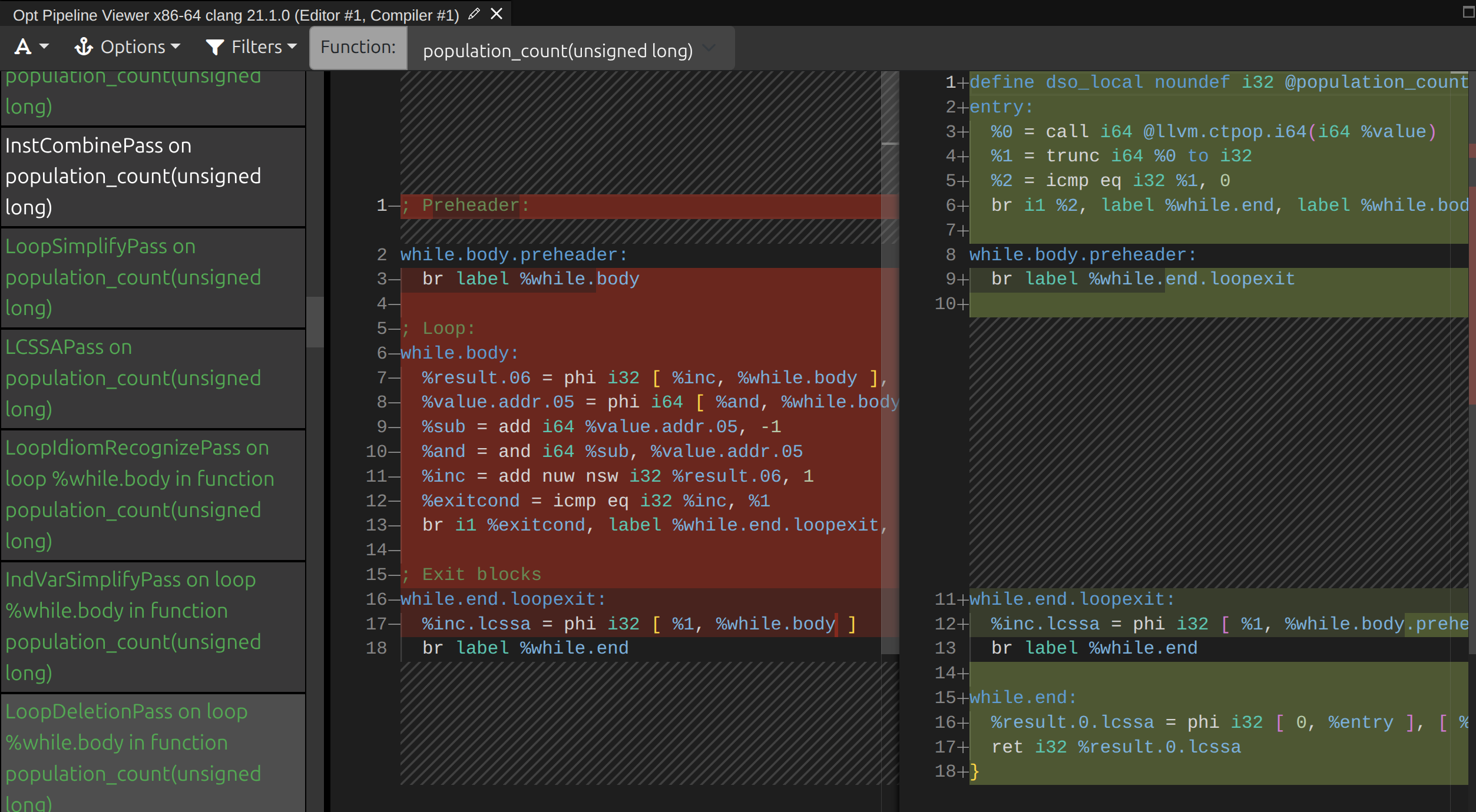

Wow! The entire routine has been replaced with a single instruction - popcnt rax, rdi. When I first saw this optimisation I was blown away: the compiler recognises a relatively complex loop as being functionally equivalent to a single instruction. Both gcc and clang can do this, and within Compiler Explorer you can use the optimisation pipeline viewer in clang to see that clang’s “loop deletion pass” is responsible for this trick:

Compiler Explorer's Opt Pipeline View

Compilers canonicalise code too, so some similar population count code will also be turned into a single instruction, though sadly not all. In this case, it’s probably better to actually use a standard C++ routine to guarantee the right instruction as well as reveal your intention: std::popcount. But even if you don’t, the compiler might just blow your mind with a single instruction anyway.

See the video that accompanies this post.

This post is day 11 of Advent of Compiler Optimisations 2025, a 25-day series exploring how compilers transform our code.

This post was written by a human (Matt Godbolt) and reviewed and proof-read by LLMs and humans.

Support Compiler Explorer on Patreon or GitHub, or by buying CE products in the Compiler Explorer Shop.