Four Million U.S. Children Had No Health Insurance in 2024. Some Will Die of Cancer

A recent analysis showed the rate of uninsured children in the U.S. grew from 2022 to 2024. Experts say this could lead to more pediatric cancer deaths

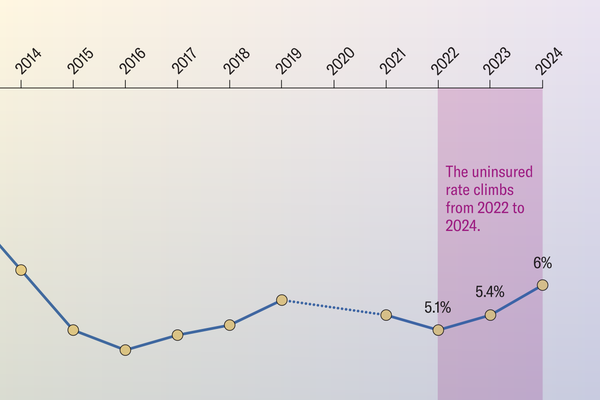

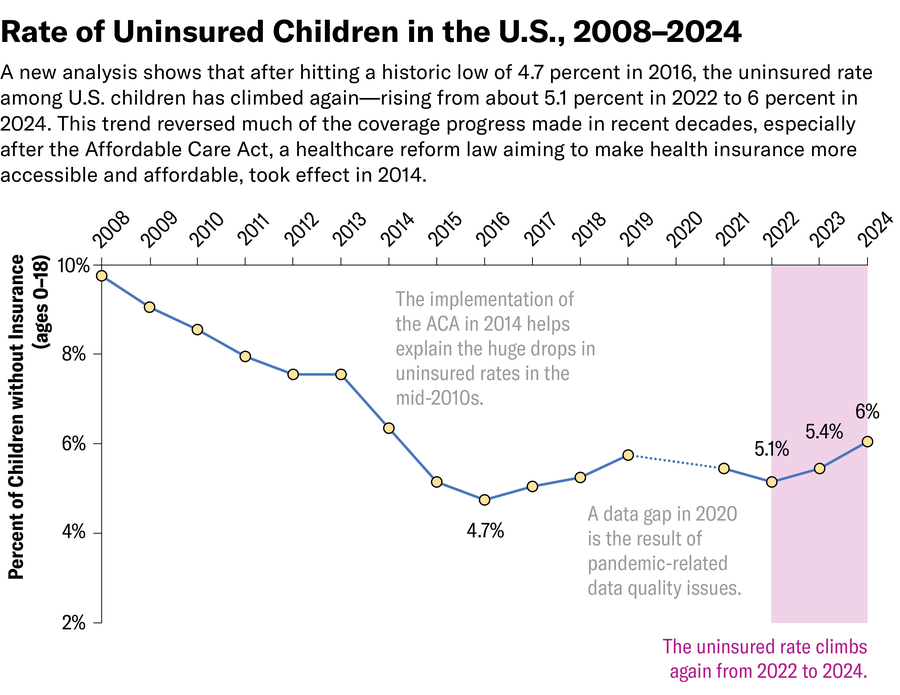

More than four million U.S. children under age 19 lacked health insurance in 2024. The uninsured rate peaked at 6.1 percent—the highest level in the past decade, according to a recent analysis by the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, a health policy research organization. That marks a nearly 20 percent increase in the number of uninsured children nationwide since 2022.

Being uninsured creates gaps in medical care. And these gaps don’t just interfere with routine pediatric care; they also disrupt treatments for serious illnesses such as pediatric cancers, for which early detection is often a matter of life and death.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“When you don’t have insurance, you’re likely to delay care,” says Kimberly Johnson, a pediatric cancer epidemiologist and a professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “In the case of cancer, that can delay diagnosis, and the cancer can become more advanced, which then is associated with a worse prognosis.”

The spike in the number of uninsured children is a direct upshot of Americans’ fragmented health care system. This patchwork of public insurance, private insurance and other employer plans creates a shaky environment for families whose income or job status changes, says Derek Brown, a health economist and a professor at Washington University in St. Louis. These life shifts may force parents to repeatedly lose and re-enroll in insurance, threatening the health of their children.

Many uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid (the government insurance program for people with limited income) or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (a joint federal-state program that provides matching federal funds for states to help insure children) but aren’t enrolled, says Joan Alker, a research professor at the Georgetown McCourt School of Public Policy. People may not know they are eligible, and individuals who are undocumented may fear deportation. “Especially in today’s climate, there are families where the child is a citizen and the parent is an immigrant, and they’re fearful of interacting with government,” Alker says. But such fears can only explain a small proportion of those who are uninsured, she notes.

More children are losing insurance because of bureaucratic red tape. In a process informally referred to as “Medicaid unwinding,” states have resumed Medicaid eligibility checks after a period of continuous coverage during the COVID pandemic. Some people who were eligible previously have been disenrolled not as a result of disqualification but simply because of bureaucratic mistakes.

These gaps in insurance coverage will result in more children getting sicker and dying. A 2020 national study in the International Journal of Epidemiology of more than 58,000 children and adolescents under age 20 with cancer found that those who were uninsured faced a sharply higher risk of dying within five years than those with private insurance across most cancer types. Eleven percent of the uninsured study participants received no cancer-directed treatment compared with 6.7 percent of those who were privately insured. Children and adolescents without insurance also had 31 percent higher odds of being diagnosed at a later stage of cancer and were 32 percent more likely to die in the five years after diagnosis than those with private insurance—living about two months less on average.

In the study, those on Medicaid also had a higher risk of dying than those on private insurance, suggesting that other differences between the groups could explain the former’s higher mortality rate, such as family income level.

Because different types of cancer grow differently, however, insurance gaps don’t harm every child in the same way. For certain types, the earlier they were found, the higher survival rates tended to be. For example, in tumors of the reproductive organs, the study found that about 40 percent of the survival difference between the privately insured and the uninsured was explained by catching the disease at a later stage, whereas for brain and spinal tumors, timing of diagnosis made little difference no matter what insurance they had—likely because the latter type of cancer tends to be less treatable in general.

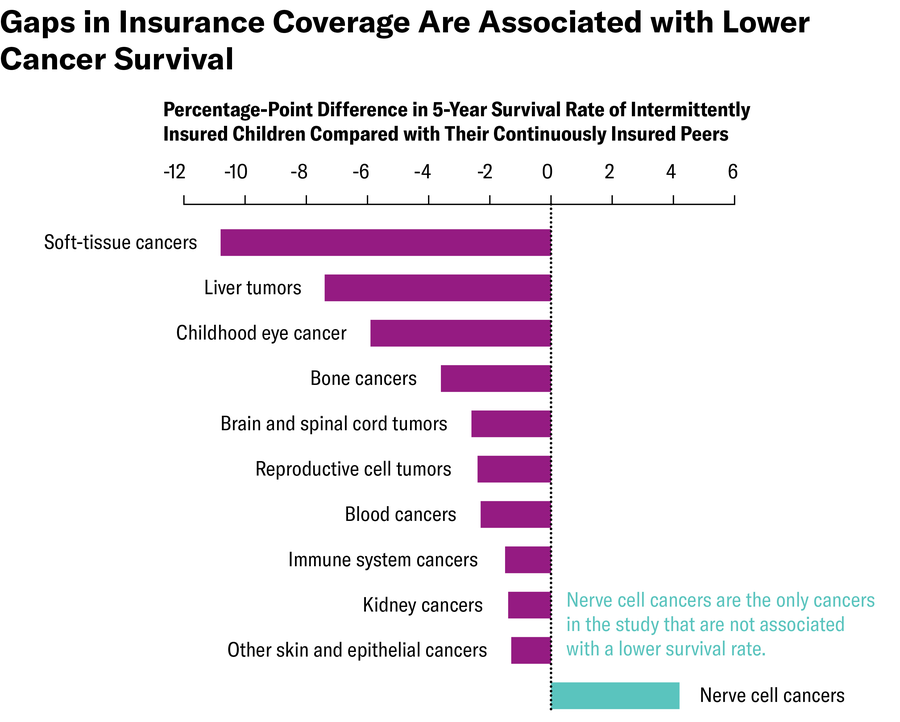

Even if kids have insurance some of the time, going on and off Medicaid can jeopardize cancer treatment. In a 2024 study in Pediatric Blood & Cancer that looked at more than 30,000 children and adolescents under age 20 who were diagnosed with cancer between 2006 and 2013, Johnson, Brown and their colleagues found that those who were intermittently insured by Medicaid during the assessment period had double the odds of being diagnosed at a later stage when cancer had metastasized and faced an increased risk of cancer death compared with their continuously insured and non-Medicaid-insured peers—most of whom had private insurance.

The five-year survival gap was widest among children and adolescents with soft-tissue cancers and liver tumors, for whom losing Medicaid coverage could interrupt lifesaving treatment; nerve-cell cancers were the only cancers that didn’t follow this trend. People with other types of cancers, such as leukemia, a form of blood cancer, also benefited from continuous insurance. Leukemia symptoms are often urgent enough to send children to the emergency room, leading to faster diagnosis, unlike many quiet-progressing solid tumors, whose symptoms parents may not recognize as urgent.

“As a country, we’re long overdue to move to a system where no baby leaves the hospital without [insurance] coverage, just the same way they shouldn’t leave the hospital without a car seat,” Alker says. The Trump administration is phasing out a policy that has allowed some states to cover children continuously until age six despite any family’s changes in circumstances.

The situation isn’t hopeless, experts say. Paperwork errors could be fixed, and legislators could make new guarantees to stop children from losing insurance. In addition, hospital and clinical social workers should help people stay connected with Medicaid enrollment supports and guide them through some of common pitfalls and challenges, Brown says. For caregivers of children with cancer, it’s especially important to make sure each state’s Medicaid enrollment process is accessible, which requires clear websites and adequate staffing, he says.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can't-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world's best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.