Hello there!

As usually, long time not updating the blog (8 months 😟)… good news is that this week I am on vacation, so I have a little more free time. There are two non-AI related technologies that me and my team created in the year 2025 that I wanted to talk about (in these months, everyone seems to talk about AI, but that is another story):

- The Micro-executive, which allows the OS to updates PTEs on ARM64 respecting the break-before-making rule.

- An attestable Anti-cheat report, designed to prevent cheat kernel modules to be loaded when a game is running.

Since #1 is too much MM state machines, I have decided to go with #2. I can return to #1 in case I will get interest from readers. So what is an attestable report? Before talking about it, we should first give an introduction about how the TPM works, why it is important, and how it could be leveraged to protect against cheaters in competitive video games (I personally love Doom, but far to be competitive 🤣) .

So, let’s start by talking about what is a TPM. There is a lot of literature available online that generally describes the TPM, or Trusted Platform Module as a “dedicated security chip that securely stores cryptographic keys and performs cryptographic operations to protect your computer’s hardware and software integrity, acting as a root of trust for the boot process”. This definition is pretty abstract: the reality is that the TPM does a lot of things (interested readers can check the amazing “A practical guide to TPM 2.0” by Will Arthur and David Challenger). This write-up will not describe the TPM in details, but, for the sake of the “anti-cheat” discussion, the TPM:

- Provides a way for the OS to mathematically prove that certain areas of (boot) code and data have not been tampered with.

- Provides a way to external (or remote) entities to prove that they are really talking to a real authentic TPM

- Provides to the OS an hardware mechanism to store encryption keys that can potentially be made available only if the integrity of certain “measurements” is guaranteed.

This write-up assumes that the reader knows the theory behind the public/private (or asymmetric) encryption method. If not, I invite the reader to take a look at the public literature.

The TPM has a list of Platform Configuration Registers (PCRs) which supports a main cryptographic operation called “Extend”, similar, but not identical, to “hashing”: you can verify that an hash is correct only if you know the original data, but not vice versa (you can not recover the original data just from an hash). Similarly, a TPM Extend operation is another cryptographic function that securely updates a PCR by hashing the current PCR value with a new measurement, creating a cumulative, tamper-evident record. Thus, the Extend operation has another important property: you can extend a PCR every time you want, but the final result always depends on both the previous and new data, implicitly building a so called chain of measurements.

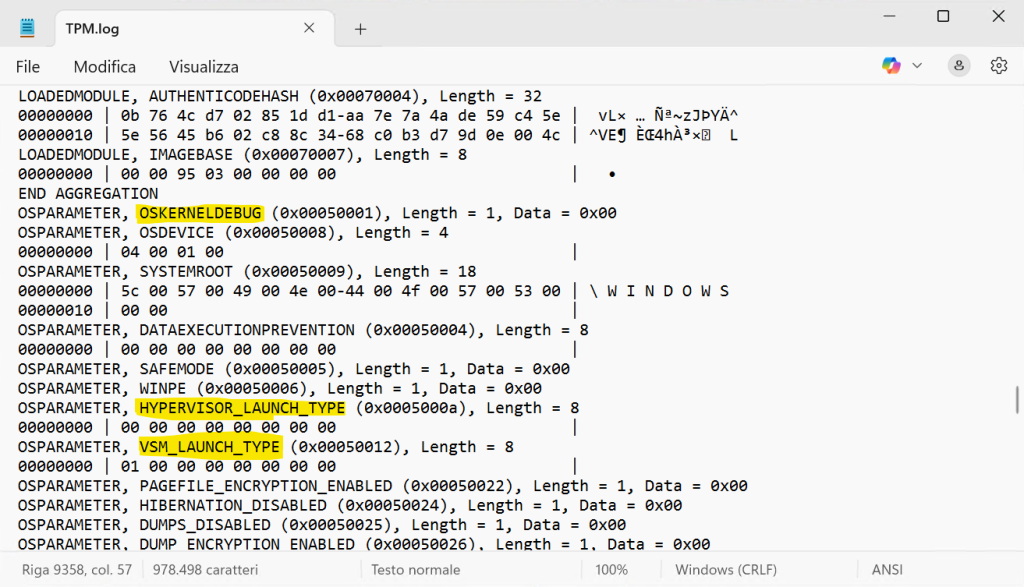

The OS maintains a “record” of the list of the measurements that generates the final PCR values in a “TCG log” (which does not have any size limit). The TCG log itself is not signed, but the final list of PCR values can be retrieved from the TPM with a Quote request (interested readers can take a look at the TpmApiQuote2 function), which is signed with an Attestation Identity Key (or AIK).

The purpose of the AIK is to sign data (PCR values) to prove that they originate from a real TPM, without having been tampered with. Hence, the AIK is the root of trust of the TPM. Careful readers can ask… how an external entity can prove that the AIK is really generated by a TPM?

If so, this is a nice question which requires going into a little more details. Every TPM is provisioned in its fuses with a secret Endorsement Key (or EK), which is particular per TPM, and by which the TPM never directly exposed its private part. The AIK, being a normal public/private key pair generated by the TPM, can be trusted in one of two ways:

- Using an AK (Attestation key) certificate chain, which is signed by a third party Attestation Certificate Authority, proving that the TPM is genuine (via its EK)

- Using the public part of the EK to encrypt (or wrap) the AIK public key. Since only the TPM can decrypt the public key, the remote entity can attest that the TPM is legit.

I know, is confusing… Skipping all the inner details (for those, take a look at these two articles: 1, 2), the reader should assume that the AIK is really the root of trust of the TPM, and it can not be forged. This means that the TPM quote can be attested to be correct and generated by a real TPM.

But, since any extend operation can not be forged either, with the TCG log and the signed TPM quote, a remote entity can attest also that every measurement is correct (thus, since the OS loader measures various parts of kernel code and data, the remote server can also be sure that the OS boot has not been tampered with).

We only need to discuss the last piece of the puzzle. Certain encryption keys used by the OS can be generated via the TPM and can be “sealed” using the content of certain PCRs being in a particular state. Thus, on the next boot, in case a single PCR value is not what is expected by the TPM, the TPM will refuse to “unseal” the key.

Furthermore, the OS can also measure the value of the public part of an encryption key previously “unsealed” by the TPM, allowing a remote entity to indirectly verify that the key has been generated in a “trusted” baseline (since the public part is present in the TCG log, and the final PCR values are signed).

We explained enough TPM details which are fundamentals for the attestable driver report. Let’s see how this work and the problem that is going to (try to) solve… Note that the TPM is usually implemented as a small chip soldered in the computer’s main board. The Microsoft Pluton implementation (and other form of newer TPMs) can also be soldered in the SOC (system-on-chip), making very difficult for a person to forge it or bypass its security characteristics.

How people cheat in video-games

There are a myriad of ways for a player to cheat in a competitive video game. I never really understood how people enjoy winning a match in a unfair way, but I am probably too naïve (especially since now there are also tournaments where players win monetary awards). Anyway, to summarize, a technically skilled player can cheat by:

- Modifying the code or data of the game engine directly from another piece of software (in this case we say that the CPU is modifying the target game memory).

- Using specialized hardware able to perform malicious DMA to transparently change the content of the game engine code or data in memory while the game is executing.

There are multiple game vendors and companies that have created anti-cheat solutions to mainly prevent cheating using external software (case #1 described above). The solutions kind of work well, and usually execute in a higher privilege environment than the video game (for example, a kernel driver or even a customized Hypervisor). Solving #2 is not trivial. A game can always require a IOMMU (again, I assume that the reader knows what a IOMMU is, if not, check here) and refuse to start in case it is missing or disabled, but the IOMMU is not always able to protect malicious DMA into the entire VTL 0 memory, where NT kernel and drivers resides (note that the IOMMU protects the entire secure memory where the Hypervisor and Secure Kernel run though). This is because of performance and complexity reasons which resides in the Memory manager implementation (remember, players do not want to loose a single frame and Windows should still be competitive in Gaming).

So, how we tried to solve the issue? Since we could not prevent malicious DMAs to happen – cheaters have also built faked PCI-Ex peripherals (for example disguised as sounds cards) for being able to pass undetected by the anti-cheat engines – we used a different approach: an attestable driver report.

The latest Windows Insider release (or the future 1B non-security patch of 25H2, which will be available in January 2026) includes a new API available only when HVCI is on, and callable from any user-mode application: GetRuntimeAttestationReport (note that the following definition is included in the latest Windows Insider SDK).

#define RUNTIME_REPORT_PACKAGE_VERSION_CURRENT (1)

typedef enum _RUNTIME_REPORT_TYPE {

RuntimeReportTypeDriver = 0,

RuntimeReportTypeCodeIntegrity = 1,

RuntimeReportTypeMax

} RUNTIME_REPORT_TYPE;

BOOL GetRuntimeAttestationReport (

UCHAR* Nonce,

UINT16 PackageVersion,

UINT64 ReportTypesBitmap,

_Out_ PVOID ReportBuffer,

_Inout_ PUINT32 ReportBufferSize);A user-mode application would initially calculate the needed memory buffer size by simply invoking the API specifying a 32-byte nonce (containing random bytes) and a UINT32 bitmap containing bit 0 set to 1.

Then, the application allocates a new memory buffer, and call again the API: this time the system will invoke the Secure Kernel (via a QUERY_RUNTIME_ATTESTATION_REPORT secure call). The Secure Kernel generates a signed and attestable report containing descriptors for all the kernel modules ever loaded by the OS (yes, it also includes unloaded drivers) and copies it into the target buffer.

Before understanding which kind of information a game can extract from the report, and discuss how the report is composed, let’s take a step back and understand how a remote entity (the video game server in this case) can prove that the report is intact and produced by the Secure Kernel, which is considered part of the TCB (Trusting computing base).

Remote Attestation of the Driver report

What does a game engine can do when it has obtained a signed driver report? Why this can be helpful in detecting cheaters? Astute readers should probably already know how to answer these questions… but let finalize the topic here to clear all the doubts (or at least I will try)….

In the first part of this write-up we talked about the TPM and how the system can retrieve a signed TPM quote. A TCG log instead contains all the measurements that made to the final values of the PCRs contained in the quote. Note that on boot, Windows measures the status of many security features, like whether HVCI is on, the presence of a IOMMU, of any debugger, and so on…

This means that, when a competitive video-game server wants to verify (or attest) that a player is using the game in a safe environment it can:

- Ask the TPM quote, a copy of the TCG log and the Driver report to the client’s game engine. The client transfers the data to the server via regular means (TCP/IP connection, named pipes or similar…)

- Starting from a value of 0, reproduce the various measurements listed in the client’s TCG log. At the end, the server calculates the final PCRs values.

- Compare the calculated PCRs values with the one located in the TPM quote. If they do not match, it means that the client environment has been modified (so the game should not be allowed to continue).

- Otherwise, verify that the TPM quote is signed correctly by checking the public part of the AIK. This means that it has been generated by a real TPM (these four described steps are part of the standard “attestation” procedure).

- If the security properties enabled in the client system (and measured into the TCG log) are the ones required by the game, proceed in parsing the Driver report. Otherwise stop and do not allow the game to run.

- Check the driver report signature: the public part of the signing key should match the Secure Kernel signing IDK, which has been measured into the TCG log. This proves that the Driver report has been really generated by the Secure Kernel, which is part of the TCB.

- Parse each kernel module listed in the report. Check each hash and blacklist any driver that has been signed by a malicious actor, drivers that are known to contains bugs exploitable by a cheater, or kernel modules that are used to control malicious hardware (like the ones that perform faked DMA transfers).

- If all the verification succeeded, allow the game to run. Every arbitrary number of minutes, request a new driver report from the client. Note that the TCG log is not needed anymore, as long as the TPM quote does not change (which means that the system integrity has not changed).

It does not matter if the malicious driver has been unloaded after performing its game modifications for allowing the player to cheat: the report will also list kernel modules that have been briefly loaded and then discarded.

Careful readers can ask… what if a cheating kernel module is loaded manually, without notifying the OS? In that case, the driver would be still listed in the report?

Yes, correct, in that case the report would miss it, but there is a catch. Since the driver report is available only when HVCI is on, there is no way in which a cheater can load any kind of executable code in NT, without passing through the Secure Kernel (which is trusted), since all Kernel memory is marked as not-executable in the Hypervisor Stage-2 translation tables (or in the Second Level Address Translation in Intel terms).

Content of the Attestable report

At the time of this write-up, Windows supports two types of attestable reports: code integrity and drivers. Explaining what a is inside the Code Integrity report is outside the scope of this blog post. Instead, a driver report contains a list of kernel module descriptors (described by the _DRIVER_INFO_ENTRY data structure, contained in the “winnt.h” file of the public Insider SDK) and a bunch of flags.

An individual kernel module descriptor contains the following data:

- A human readable name of the NT kernel module.

- The full image’s SHA256 hash.

- The SHA1 hash of the entire module’s leaf certificate that has passed code integrity validation (this can always be the same for each WHQL driver, that is why we added also the OEM name).

- The number of loading and unloading times

- A human readable string of the OEM name stored in the authenticated OPUS block of the digital signature

- Some flags describing the state of the module (whether is currently unloaded, or whether is an hotpatch).

Conclusions and possible attack vectors

The technique discussed in this write-up is aimed to prevent cheaters to easily modify a game engine with the goal to have unfair advantages in competitive gaming. In this blog post we voluntarily did not talk about possible attack vectors, leaving it as a homework for the readers (spoiler: there is an attack vector that is very hard to be laid out).

Note that describing why the Secure Kernel and the Hypervisor are part of the Trusted Computing Base (TCB) is outside the scope of this write up, since it will require another entire article. The idea is that if one of these two components is owned by a malicious actor, is already a game-over (and the system would be owned). A lot of technologies like Secure Boot, Secure Launch, Trusted Boot (and others…) exist to protect and keep them part of the TCB.

I would be happy to talk about possible bypasses that the reader can find. If you have some questions or you want to discuss a possible attack vector just drop me a message on X (my handle is @aall86) or via regular e-mail ([email protected])

This is all for now folks!

Wish you all a Great Year 2026! 🎉🎉🎊

Andrea