I would like to thank Yann Régis-Gianas, Sylvain Ribstein and Paul Laforgue for their feedback and careful review.

To kick off 2026, I had clear objectives in mind: decommissioning moana, my

trusty $100+/month VPS, and setting up tinkerbell, its far less costly

successor.

On the one hand, I have been using moana to self-host a number of services,

and it was very handy to know that I had always a go-to place to experiment

with whatever caught my interest. On the other hand, $100/month is obviously a

lot of money, and looking back at how I used it in 2025, it was not

particularly well spent. It was time to downsize.

Now that tinkerbell is up and running, I cannot even SSH into it. In fact,

nothing can.

There is no need. To update one of the services it hosts, I push a new container

image to the appropriate registry with the correct tag. tinkerbell will fetch

and deploy it. All on its own.

In this article, I walk through the journey that led me to the smoke and mirrors behind this magic trick: Fedora CoreOS , Ignition and Podman Quadlets in the main roles, with Terraform as an essential supporting character. This stack checks all the boxes I care about.

Note

For interested readers, I have published tinkerbell’s full setup on

GitHub. This article reads as an experiment log, and if you are only

interested in the final result, you should definitely have a look.

Container-Centric, Declarative, and Low-Maintenance

Going into this, I knew I didn’t want to reproduce moana’s setup—it was fully

manual

and I no longer have the time or the motivation to fiddle with

the internals of a server. Instead, I wanted to embrace the principles my

DevOps colleagues had taught me over the past two years.

My initial idea was to start with this very website, since it was the only

service deployed on moana that I really wanted to keep. Since I had written

a container image for this website, I just had to look

for the most straightforward and future-proof way to deploy it in production™—

something I could later extend to deploy more cool projects, if I ever wanted

to

.

Docker Compose alone wasn’t a good fit. I like compose files, but one needs to provision and manage a VM to host them. Ansible can provision VMs, but that road comes with its own set of struggles. Writing good playbooks has always felt surprisingly difficult to me. In particular, a good playbook is supposed to handle two very different scenarios—provisioning a brand new machine, and updating a pre-existing deployment—and I have found it particularly challenging to ensure that both paths reliably produce the same result.

Kubernetes was very appealing on paper. I have seen engineers turn compose

files into Helm charts and be done with it. If I could do the same thing,

wouldn’t that be bliss? Unfortunately, Kubernetes is a notoriously complex

stack, resulting from compromises made to address challenges I simply don’t

face. Managed clusters could make things easier, but they aren’t cheap. That

would defeat the initial motivation behind retiring moana.

CoreOS , being an operating system specifically built to run containers, obviously stood out. That said, I had very little intuition on how it could work in practice. So I started digging. I learned about Ignition first. Its purpose is to provision a VM exactly once, at first boot. If you need to change something afterwards, you throw away your VM and create a new one. This may seem counter-intuitive, but since it eliminates the main reason I was looking for an alternative to Ansible, I was hooked .

I found out how to use systemd unit files to start containers via podman CLI

commands. That was way too cumbersome, so I pushed on for a way to orchestrate

containers à la Docker Compose. That’s when I discovered Podman Quadlets and

auto-updates .

With that, everything clicked. I knew what I wanted to do, and I was very excited about it.

Assembling tinkerbell

For more than a year now, my website has been served from RAM by a standalone,

static binary built in OCaml, with TLS termination handled by Nginx and

certbot’s certificates renewal performed by yours truly

. I didn’t

have any reason to fundamentally change this architecture. I was simply looking

for a way to automate their deployment.

Container-Centric, …

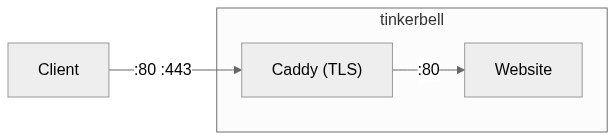

The logical thing to do was to have tinkerbell run two containers:

Nothing beats a straightforward architecture

Nothing fancy or unexpected here, which made it a good target for a first deployment. It was time to open Neovim to write some YAML.

Declarative, …

At this point, the architecture was clear. The next step was to turn it into something a machine could execute. To that end, I needed two things: first an Ignition configuration, then a CoreOS VM to run it.

The Proof of Concept

Ignition configurations (.ign) are JSON files primarily intended to be

consumed by machines. They are produced from YAML files using a tool called

Butane . For instance, here is the first Butane configuration file I ended up

writing. It provisions a CoreOS VM by creating a new user (lthms), along with

a .ssh/authorized_keys file allowing me to SSH into the VM

.

variant: fcos

version: 1.5.0

passwd:

users:

- name: lthms

ssh_authorized_keys:

- ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIKajIx3VWRjhqIrza4ZnVnnI1g2q6NfMfMOcnSciP1Ws lthms@vanellope

What’s important to keep in mind is that Ignition runs exactly once, at first boot. Then it is never used again. This single fact has far-reaching consequences, and is the reason why any meaningful change implies replacing the machine, not modifying it.

Before going any further, I wanted to understand how the actual deployment was going to work. I generated the Ignition configuration file.

butane main.bu > main.ign

Then, I decided to investigate how to define the Vultr VM in Terraform. The resulting configuration is twofold. First, we need to configure Terraform to be able to interact with the Vultr API, using the Vultr provider . Second, I needed to create the VM and feed it the Ignition configuration.

resource "vultr_instance" "tinkerbell" {

region = "cdg"

plan = "vc2-1c-1gb"

os_id = "391"

label = "tinkerbell"

hostname = "tinkerbell"

user_data = file("main.ign")

}

And that was it. I invoked terraform apply, waited for a little while, then

SSHed into the newly created VM with my lthms user. Sure enough, the

tinkerbell VM was now listed in the Vultr web interface. I explored for a

little while, then called terraform destroy and rejoiced when everything

worked as expected.

The MVP

At this point, I was basically done with Terraform, and I just needed to write

the Butane configuration that would bring my containers to life. As I mentioned

earlier, the first approach I tried was to define a systemd service responsible

for invoking podman.

systemd:

units:

- name: soap.coffee.service

enabled: true

contents: |

[Unit]

Description=Web Service

After=network-online.target

Wants=network-online.target

[Service]

ExecStart=/usr/bin/podman run \

--name soap.coffee \

-p 8901:8901 \

--restart=always \

ams.vultrcr.com/lthms/www/soap.coffee:latest

ExecStop=/usr/bin/podman stop soap.coffee

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Adding this entry in my Butane configuration and redeploying tinkerbell got

me exactly what I wanted. My website was up and running. For the sake of

getting something working first, I added the necessary configuration for Caddy

(the container and the provisioning of its configuration file), redeployed

tinkerbell again, only to realize I also needed to create a network so that

the two containers could talk together. After half an hour or so, I got

everything working, but was left with a sour taste in my mouth.

This would simply not do. I wasn’t defining anything, I was writing a shell script in the most cumbersome way possible.

Then, I remembered my initial train of thought and started to search for a way to have Docker Compose work on CoreOS . That is when I discovered Quadlet, whose initial repository does a good job justifying its existence . In particular,

With quadlet, you describe how to run a container in a format that is very similar to regular systemd config files. From these actual systemd configurations are automatically generated (using systemd generators ).

To give a concrete example, here is the .container file I wrote for my

website server.

[Container]

ContainerName=soap.coffee

Image=ams.vultrcr.com/lthms/www/soap.coffee:live

[Service]

Restart=always

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

I wasn’t wasting my time teaching systemd how to start containers anymore. I was now declaring what should exist, so that systemd—repurposed for the occasion as a container orchestrator—could take care of the rest.

Tip

If your containers are basically ignored by systemd, be smarter than me. Do

not try to blindly change your .container files and redeploy your VM in a

very painful and frustrating loop. Simply ask systemd for the generator logs.

sudo journalctl -b | grep -i quadlet

I excitedly turned caddy.service into caddy.container, redeployed

tinkerbell, ran into the exact same issue I had encountered before and

discovered the easiest way for two Quadlet-defined containers to talk to each

other was to introduce a pod . Unlike Docker Compose which uses DNS

over a bridge network, a pod shares the network namespace, allowing containers

to communicate over localhost.

To define a pod, one needs to create a .pod file, and to reference it in

their .container files using the PodName= configuration option. A “few”

redeployments later, I got everything working again, and I was ready to call it

a day.

And with that, tinkerbell was basically ready.

Caution

I’ve later learned that restarting a container that is part of a pod will have the (to me, unexpected) side-effect to restart all the other containers of that pod.

And Low-Maintenance

Now, the end of the previous section might have given you pause.

Even a static website like this one isn’t completely “stateless.” Not only does Caddy require a configuration file to do anything meaningful, but it is also a stateful application as it manages TLS certificates over time. Besides, I do publish technical write-ups from time to time .

Was I really at peace with having to destroy and redeploy tinkerbell every

time I need to change anything on my website?

On the one hand, yes. I believe I could live with that. I modify my website only a handful of times even in good months, I think my audience could survive with a minute of downtime before being allowed to read my latest pieces. It may be an unpopular opinion, but considering my actual use case, it was good enough. Even the fact that I do not store the TLS certificates obtained by Caddy anywhere persistent should not be an issue. I mean, Let’s Encrypt has fairly generous weekly issuance limits per domain . I should be fine.

On the other hand, the setup was starting to grow on me, and I have other use cases in mind that could be a good fit for it. So I started researching again, this time to understand how a deployment philosophy so focused on immutability was managing what seemed to be conflicting requirements.

I went down other rabbit holes, looking for answers. The discovery that stood out the most to me—to the point where it became the hook of this article—was Podman auto-updates.

To deploy a new version of a containerized application, you pull the new image and restart the container. When you commit to this pattern, why should you be the one performing this action? Instead, your VM can regularly check registries for new images, and update the required containers when necessary.

In practice, Podman made this approach trivial to put in place. I just needed

to label my containers with io.containers.autoupdate set to registry,

enable the podman-auto-update timer

, and that was it. Now, every

time I update the tag www/soap.coffee:live to point to a newer version of my

image, my website is updated within the hour.

And that is when the final piece clicked. At this point, publishing an image becomes the only deployment step. I didn’t need SSH anymore.

The Road Ahead

tinkerbell has been running for a few days now, and I am quite pleased with

the system I have put in place. In retrospect, none of this is particularly

novel. It feels more like I am converging toward a set of practices the

industry has been gravitating toward for years.

A man looking at the “CoreOS & Quadlets” butterfly and wondering whether he’s looking at Infrastructure as Code. I’m not entirely sure of the answer.

The journey is far from being over, though. tinkerbell is up and running, and

it served you this HTML page just fine, but the moment I put SSH out of the

picture, it became a black box. Aside from some hardware metrics kindly

provided by the Vultr dashboard, I have no real visibility into what’s going on

inside. That is fine for now, but it is not a place I want to stay in forever.

I plan to spend a few more weekends building an observability stack

.

That will come in handy when things go wrong—as they inevitably do. I would

rather have the means to understand failures than guess my way around them.

Did I ever mention I am an enthusiastic Opentelemetry convert?