Why Feature Selection?

Let’s say that you’re a junior Machine Learning Engineer working at a bank, and you’ve been tasked with building a model that predicts if a customer will default on a loan or not. Before you build your classifier, you talk to your colleagues in Analytics, and they claim that there are approximately 500 factors that go into determining if someone is unable to pay their loans. You, however, want to find top 15 most relevant features to train your classifier with because you want to keep your model light and transparent. How do you proceed? In other words, how do you go from 500 features overall down to just 15 best?

Whether you want to simplify your model, reduce training time, address the above scenario, or follow any one of these uses of Feature Selection, you will want to learn a few good methods to select top $k$ features before you start training your model.

That’s what I hope you’ll take away from this article. I know there are hundreds (if not thousands) of guides on this very topic on the internet, but very few of them focus on the statistical background of these methods. I noticed that they all just talk about Feature Selection on a surface level instead of digging deep into the theory and hard math involved in the process, which I think is essential if you want to build strong intuition around Feature Selection methods and master them well.

Structure

This article will be structured in the following way: first, I’ll walk you through a short introduction to a method; second, I’ll cover any prerequisites that you will probably need to understand the method — for example, explaining what Covariance is before the Correlation Coefficient. Then, I’ll go over the formula plus the math behind how the method works (if there is any) to build intuition for how/why the method works, and also for when this method is applicable. Finally, I’ll tie everything up and provide an implementation in code to make sure you’ve fully grasped the concept and are ready to apply it for your own case.

Note that some mathematical concepts mentioned throughout the article (expectation, variance, etc.) are re-occurring, so to avoid explaining them every time they’re mentioned, I’ve put them in the Appendix. If you’re unfamiliar with these concepts, I strongly suggest that you spend a bit of time understanding them, as they’re a crucial part of every major feature selection method.

For the record, there are many approaches to feature selection, and all of them are usually grouped into four families of methods: Unsupervised and Supervised, which in itself consists of three groups: Wrapper methods, Filter methods, and Embedded methods. In this blog, we’ll discuss the most commonly used family of methods — Filter. Filter methods rely on analyzing each feature’s statistical relationship with the target variable as an indicator for the model’s performance. They’re fast, easy, and quite convenient to work with if you’re tackling classical ML problems.

If you want to read more about the other families of feature selection methods, here’s a link to Wrapper methods, and this is a Wikipedia reference to all the methods.

Levels of Measurement

Alright, one last thing before we start discussing Filter methods, I promise. We first have to agree on what “kind” of data we are looking at while doing feature selection. What I mean is, in statistics, data isn’t just numbers or text; it falls into a specific hierarchy of information known as the Levels of Measurement, so I’ll try explaining it here the way I was taught in college.

There are four levels of measurement, ranging from the simplest (least information) to the most complex (most information):

- Nominal: This is data that acts only as a label; i.e. there is no order and no distance.

- Examples: $Eye Color (Blue, Brown, …), City (Tashkent, Ithaca, …).$

- You can only count them; for instance, you can’t say $”Blue > Brown”$.

- Ordinal: This is data where the order matters, but the distance between values is unknown or inconsistent.

- Examples: T-Shirt Sizes $(S, M, L)$, Satisfaction Surveys $(Good, Neutral, Dogsh*t).$

- You can say $”L > M”$, but you can’t say “$L-M=S$.”$\;$ In other words, you know the direction, but you don’t know the scale of difference.

- Interval: Here, the order matters and the distance between values is equal and meaningful. However, there is no “True Zero” (a zero point doesn’t mean “none” or “absence”).

- Examples: Temperature in Celsius/Fahrenheit ($0^\circ C$ is cold, not “no heat”), Calendar Years (Year 0 isn’t the beginning of time).

- You can add and subtract, but you cannot multiply or divide. You can’t say “$20^\circ C$ is twice as hot as $10^\circ C$” (yeah, this kind of took me by surprise when I first learned about it too).

- Ratio: This is the highest level of data. It has order, equal distance, and a “True Zero” (0 means the total absence of the variable).

- Examples: Height, Weight, Salary, Counts (0 items sold), Age, etc.

- You can do everything. Because zero is real, you can say “A person weighing 100 kilos is exactly twice as heavy as someone weighing 50”.

The reason I’m talking about Levels of Measurement in data is that feature selection methods are strict about this hierarchy. What I mean is, you cannot use a method designed for Ratio data (like Pearson’s $r$) on Nominal data. However, you generally can use a method designed for a lower levels (like Nominal) on higher levels (like Ratio) by kind of “downgrading” your data; for example, grouping you friends’ ages into age buckets.

Cool? Alright, let’s get started.

Filter Methods

Pearson’s R:

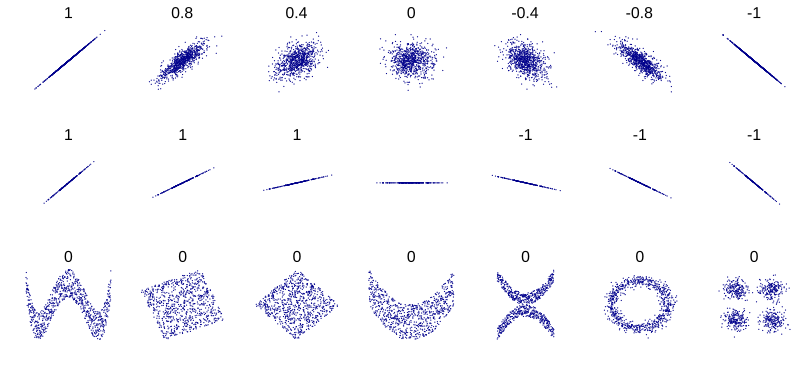

The first filter method we’re going to look at is Pearson’s $r$ (correlation coefficient). The correlation coefficient measures the strength and the direction of a linear relationship between two variables, and it does so by measuring the Covariance between them.

For two variables $X$ (age of every student in a classroom) and $Y$ (height of every student in a classroom), with respective means $\mu_X$ and $\mu_Y$, the covariance between $X$ and $Y$ is defined as

\[Cov(X, Y)=E[(X-\mu_X)(Y-\mu_Y)]\]Let me explain what this formula computes:

- $(X-\mu_X)$: each student’s age minus the average age in the classroom

- $(Y-\mu_Y)$: each student’s height minus the average height in the classroom

- $P=(X-\mu_X)(Y-\mu_Y)$: let’s temporarily define this as the product of the two differences

- $E[P]$: this measures the expected value of $P$. In other words, it measures the weighted average of the values of $P$ (if this is unclear, see the appendix on Expectation). You can interpret this as the average product between $[$the differences for each student’s age, height and their corresponding averages$]$.

Covariance will be positive when large values of $X$ are associated with large values of $Y$ and small values of $X$ are associated with small values of $Y$. On the other hand, if $X$ are $Y$ are inversely related, most product terms will be negative, as when $X$ takes values above the mean, $Y$ will tend to fall below the mean, and vice versa.

Covariance is a measure of linear association between two variables. In a sense, the “less linear” the relationship, the closer the covariance is to 0.

The sign of the covariance indicates whether two random variables are positively or negatively associated. But the magnitude of the covariance can be difficult to interpret due to the scales of the original variables, which is where the correlation coefficient comes in.

Pearson’s $r$, takes the covariance between two variables and divides it by the product of their respective standard deviations - a measure of variation around the mean (see the appendix on what that is), thus making the correlation fall in the range of $[-1,1]$ and the value meaningful.

\[Corr(X, Y)=\frac{Cov(X, Y)}{SD[X]SD[Y]}\]The properties of correlation are as follows:

- $-1 \leq Corr(X,Y) \leq 1$

- If $Y=aX+b$ is a linear function of $X$ for constants $a$ and $b$, then $Corr(X,Y)= \pm1$, depending on the sign of $a$.

The first property says the correlation coefficient is always between $-1$ and $1$ (see this section if you’re interested in a proof). If it is $-1$ or is close to it, that means there is a strong negative linear association between the two variables; if it’s around $1$, the relationship is still strong but positive. As the coefficient approaches $0$, the association between the variables also diminishes.

The second property states that when the correlation coefficient of two variables $X$ and $Y$ is exactly $1$ or $-1$, then we can express one variable as a perfect linear function of the other with no random noise whatsoever, meaning the two variables are perfectly correlated.

Pearson’s R is applicable when the features are of the following categories:

- $X$: interval/ratio

- $Y$: interval/ratio

While selecting the “best” features for our model, the higher the Correlation Coefficient between a feature and our target variable, the better. If you wanted to build a model that predicts the Height of a student based on a number of factors, including their Age and the Number of siblings they have, you might find that Pearson’s $r$ between Height and Age is pretty high while the coefficient between Height and Number of siblings is pretty low. In this case, you should keep the first feature.

Code:

from scipy.stats import pearsonr

# x and y are continuous

corr, p_value = pearsonr(x, y)

print(f"Pearson Correlation: {corr:.3f}")

print(f"P-value: {p_value:.3e}")

Kendall’s $\tau$:

Relevant:

The next method in our toolkit is Kendall’s Tau, which is also known as Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient. Hopefully, from the previous section you know that Pearson’s $r$ measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship; Kendall’s $\tau$ on the other hand, measures the strength of an Ordinal **association between two variables.

To give an example, it answers the question “When variable $X$ gets bigger, does variable $Y$ also tend to get bigger (or smaller for that matter)?”. It doesn’t care how much bigger, only that the direction of the relationship is consistent.

Again, before we go into any formulas, I think it’s crucial to understand the building blocks of Kendall’s $\tau$, which are its concordant and discordant pairs. In order to calculate the coefficient $\tau$, we look at every possible pair of observations in our dataset (if you’re familiar with combinatorics, you’ll know that for $n$ observations, you’ll have to consider $\binom{n}{2}=\frac{n!}{2!(n-2)!}$ pairs!). For any two observations $i$ and $j$, we have the values $(x_i,y_i)$ and $(x_j,y_j)$ — the corresponding values of variables $x$ and $y$ for observations $i$ and $j$.

- Concordant Pair: A pair is concordant if the ranks of both variables move in the same direction, and this pair is expressed as $N_c$. This means that either $(x_i>x_j$ and $y_i>y_j)$, OR $(x_i<x_j$ and $y_i<y_j)$

- Discordant Pair: A pair is discordant if the ranks of the variables move in opposite directions. This pair is expressed as $N_d$. This means either $(x_i>x_j$ and $y_i<y_j)$ , OR $(x_i<x_j$ and $y_i>y_j)$

- Tied Pair: if $x_i=x_j$ or $y_i=y_j$ (we’ll come back to this).

Let’s put this all into practice with an example. Imagine we are ranking employees based on their Years of Experience and Bug Fixing Rank, where 1 is the best rank.

| Employee | Years of Experience $(X)$ | Bug Fixing Rank $(Y)$ |

|---|---|---|

| Linus | 2 | 3 |

| Steve | 5 | 1 |

| Lola | 3 | 2 |

There are $n=3$ employees, so the total number of pairs is $\binom{3}{2}=\frac{3!}{2!(3-2)!}=3$. Let’s look at each pair:

- (Linus, Steve)

- Experience: $2<5$; $X$ increased.

- Rank: $3>1$; $Y$ decreased (although a rank of 1 IS better than 3, the number 1 is still less than 3)

So this is a discordant pair.

- (Linus, Lola)

- Experience: $2<3$; $X$ increased

- Rank: $3>2$; $Y$ decreased

This is also a discordant pair

- (Steve, Lola)

- Experience: $5>3$; $X$ decreased

- Rank: $1<2$; $Y$ increased

This is also a discordant pair

Alright, in this example, we have 0 concordant pairs and 3 discordant pairs. Intuitively, this shows a perfect negative relationship: as experience goes up, the rank number goes down (i.e. the productivity rank gets better).

Kendall’s $\tau$ is essentially the difference between the number of concordant and discordant pairs, normalized to fall between -1 and 1. Tau-a:

The simplest version of the Tau statistic is Tau-a, or $\tau_A$ and is used when there are no ties in the data, as in no two $x$ values are the same and no two $y$ values are the same. The formula for it is:

\[\tau_A=\frac{N_c - N_d}{N_c+N_d}\]For our example above,

\[\tau_A=\frac{0-3}{0+3}=-1\]This shows a perfect negative ordinal relationship, just as we had predicted.

Tau-b:

In the real world though…., data almost always have ties. What if Linus and Steve both had 2 years of experience? Then the (Linus, Steve) pair would tied on X (Years of Experience).

The formula for $\tau_A$’s denominator becomes inaccurate because it assumes all pairs are either concordant or discordant (i.e. the denominator overcounts because some pairs can’t be classified as concordant or discordant at all), so we need a way to handle these ties. This is where $\tau_B$ comes in. It’s the most common version of Kendall’s correlation, and the formula adjusts the denominator to account for pairs that are tied on $x$ $(T_x)$ and pairs that are tied on $y$ $(T_y)$. The numerator is the same, but the denominator becomes the geometric mean (Appendix D) of the total pairs excluding ties on $x$ and the total pairs excluding ties on $y$.

\[\tau_B=\frac{N_c-N_d}{\sqrt{(N_c+N_d+T_x)(N_d+N_d+T_y)}}\]The properties of Kendall’s $\tau$ are as follows:

- $-1\leq\tau \leq1$

- $\tau=1$: Perfect agreement. All pairs are concordant. If you sort the data by variable $x$, variable $y$ will also be perfectly sorted in ascending order.

- $\tau=-1$: Perfect disagreement. All pairs are discordant. If you sort the data by variable $x$, variable $y$ will be perfectly sorted in descending order.

- $r=0$: No association. The number of concordant and discordant pairs is equal. The variables are independent.

A key advantage of Kendall’s $\tau$ over Pearson’s $r$ is that it can capture non-linear monotonic relationships. Pearson’s $r$ only measures linearity.

For example, let’s consider a case where as $x$ increases, $y$ always increases, but not in a straight line. Pearson’s $r$ would be positive, but not 1, Kendall’s $\tau$, on the other hand, (and Spearman’s, which we’ll see soon) would be exactly 1 because every single pair of points is concordant.

Kendall’s $\tau$ is applicable when the features are of the following categories:

- $X$: ordinal, interval, ratio

-

$Y$: ordinal, interval, ratio

Ordinal, because this is its native territory. Data like small, medium, large or good, neutral, bad can be directly compared to form concordant/discordant pairs.

Interval/ratio, because data like temperature or salary have a natural order, so they can easily be converted into buckets of ranks

As you already might have guessed, you can’t use $\tau$ with data like car, boat, plane, etc. because there is no logical order to them, that is you can’t say car > boat. It’s impossible to form a concordant or discordant pair.

Code:

from scipy.stats import kendalltau

# x and y can be ordinal or continuous

tau, p_value = kendalltau(x, y)

print(f"Kendall’s Tau: {tau:.3f}")

print(f"P-value: {p_value:.3e}")

Spearman’s $\rho$:

Relevant:

Now, let’s talk about Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, also known as Spearman’s Rho. This method is a very close cousin (brother even) to both Pearson’s $r$ and Kendall’s $\tau$ — here’s a link the Wikipedia page if you’re curious about that.

- Like Kendall’s $\tau$, it measures the strength and direction of a monotonic relationship

- Like Pearson’s $r$, it’s calculated using a familiar formula, but with a clever twist

Essentially, Spearman’s $\rho$ answers the question ‘How well can the relationship between two variables be described by a monotonic function?’. In other words, as one variable increases, does the other consistently increase or decrease, even if not at a constant rate?

The ‘twist’ behind Spearman’s $\rho$ I mentioned earlier is very elegant and easy to understand (if you understood Pearson’s $r$ that is):

Spearman’s $\rho$ is simply Pearson’s $r$ calculated on the ranks of the data, not on the data itself. That’s it!!

Instead of using raw values like $X=3,7,11$, you first convert them to ranks $X_{rank}=1,2,3$ and then use the Pearson’s $r$ formula on those ranks.

Let’s formalize this:

- Take your two variables $X$ and $Y$

- For variable $X$, rank all its observations from smallest to largest. The smallest value gets rank 1, next smallest gets rank 2, and so on. Let’s call this new function $rank(X)$

- Do the exact same thing on $Y$. Let’s also call this $rank(Y)$

- Now calculate Pearson’s $r$ between $rank(X)$ and $rank(Y)$:

By converting the raw values to ranks, you’ve thrown away all information about magnitude and distribution. You are left with only the order. This is what allows Spearman’s to detect a perfect monotonic relationship even if it’s not linear.

The properties of Spearman’s $\rho$ are as follows:

- $-1\leq\rho\leq1$

- $\rho=1$: Perfect positive monotonic relationship. As $X$ increases, $Y$ never decreases.

- $\rho=-1$: Perfect negative monotonic relationship. As $X$ increases, $Y$ never increases.

- $\rho=0$: No monotonic relationship

Alright, let’s get our hands dirty and go through a non-linear example:

| $X$ | $Y=X^2$ |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 9 |

| 4 | 16 |

| 5 | 25 |

A Pearson’s $r$ calculation on $X$ and $Y$ would not be 1 here. It would be high, but not 1 because the relationship is not a straight line because $Y$ isn’t a linear function of $X$.

A Spearman’s $\rho$ calculation would first find the ranks:

- $rank(X)=[1,2,3,4,5]$

- $rank(Y)=[1,2,3,4,5]$

And since $rank(X)$ and $rank(Y)$ are identical, the correlation between them is a perfect 1.

Spearman’s $\rho$ correctly shows this as a perfect relationship, whereas Pearson’s $r$ does not. This also shows that $\rho$ is less sensitive to outliers than $r$ — an outlier might drastically change the mean and SD (affecting $r$), but it will only change its rank by one position, having a minimal effect on $\rho$. Cool, right?

You might be asking yourself right now if Spearman and Kendall are the same. In a way, they are: they both measure monotonic relationships, so for feature selection, they will almost always lead you to the same conclusions in the same setting. So, it’s really up to you to decide which one to use, this stack exchange post discusses this very question.

Because Spearman’s $\rho$ is based entirely on ranks, its applicability is identical to Kendall’s $\tau$:

- $X$: ordinal, interval, ratio

- $Y$: ordinal, interval, ratio

See the same section in Kendall’s $\tau$ to see why.

Code:

from scipy.stats import spearmanr

# x and y can be ordinal and continuous

rho, p_value = spearmanr(x, y)

print(f"Spearman’s Rho: {rho:.3f}")

print(f"P-value: {p_value:.3e}")

Chi-Squared $(\chi^2)$ Test:

Alright, it gets interesting now. The methods we’ve discussed so far are designed to measure the correlation between variables that have some kind of order to them (ordinal, interval, or ratio). BUT, what if our variables are purely categorical, like ‘City’ $(X)$ or ‘Clicked Post’ $(Y)$? Obviously there is no natural order to ‘Berlin’, ‘Bukhara’ and ‘Bern’, so we can’t rank them or calculate a correlation. If, for some reason, you wanted to use the city someone lives in as a feature in your ML model, how exactly would you do so?

As you might’ve guessed, this is where the $\chi^2$ test comes in: Instead of measuring the correlation, the $\chi^2$ test measures independence. In other words, it answers the question “Are these two categorical variables independent of each other?”.

For feature selection, we want the opposite. We want features that are dependent on our target variable. If a feature is dependent on the target, it means knowing the feature’s value gives us information about the target’s value, so you’d better have it in your model.

The entire $\chi^2$ test is built on comparing the data we see with the data we would expect to see if the two variables were perfectly independent (in the statistical world this is called Observed vs Expected).

The first step in doing this is to put our data in a Contingency Table, which is the default way to summarize two categorical variables in statistics. Let’s do that and use an example where we measure the amount of times 1000 people played three video games.

| Played: Yes | Played: No | Row Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factorio | 90 | 410 | 500 |

| Devil Daggers | 30 | 270 | 300 |

| Icy Tower | 10 | 190 | 200 |

| Column Total | 130 | 890 | 1000 |

Now, we must calculate the Expected Frequencies $EF$ (this is the most important concept in this section). The expected frequency for a cell is the count we would see if the variables were totally independent from each other. The way we calculate the expected frequencies is as follows:

For Factorio, “Played: Yes”:

- Overall, what’s the probability of someone playing a game? Well, it’s $130/1000=13\%$

- Overall, how many people play Factorio? $500$

- If the play rate is independent of the game, then we would expect the $13\%$ play rate to apply to Factorio fans just like everyone else.

- Therefore, $EF(game, Yes)=13\%$ of $500=0.13\times500=65$. This number says that if the fact that whether someone plays a game or not is independent from the kind of the said game, we’d expect 65 people to play Factorio.

The general formula for any cell’s expected frequency is:

\[E = \frac{(Row\;Total\times Col\;Total)}{Grand\;Total}\]Plugging in the numbers from the above example, we get: $\frac{500\times130}{1000}=65$; same as before!

Using the formula, let’s build the expected frequencies table for all the games:

| Played: Yes | Played: No | Row Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factorio | 65 | 435 | 500 |

| Devil Daggers | 39 | 261 | 300 |

| Icy Tower | 26 | 174 | 200 |

| Column Total | 130 | 890 | 1000 |

Now, we look at the two tables:

- Observed (Factorio, Yes): $90$

- Expected (Factorio, Yes): $65$

As you can see, that’s a big difference! This discrepancy is the evidence that our variables might not be independent.

The $\chi^2$ Statistic: The Formula

The formula for computing the $\chi^2$ statistic uses the logic above, and the output is simply a single number that shows the total difference between the Observed $(O)$ and Expected $(E)$ tables. We calculate the difference for each cell, and then sum them all up.

The formula is:

\[\chi^2 = \sum \frac{(O-E)^2}{E}\]Let’s break this down:

- $(O-E)$: The difference for one cell. (e.g., $90-65=25)$

- $(O-E)^2$: We square difference. This does two things: First, it makes all differences$\;$ positive, so they don’t cancel each other out. Second, it heavily penalizes large differences.

- $\frac{\dots}{E}$: We normalize$\;$the difference by dividing by the expected value. This is crucial. A difference of $10$ is massive if you only expected $5$, but it’s trivial if you expected $10,000$. So this puts all differences on a relative scale.

Let’s calculate it for our example (summing $\frac{(O-E)^2}{E}$ for all $6$ sells):

- (Factorio, Yes): $\frac{(90-65)^2}{65} = 9.62$

- (Factorio, No): $\frac{(410-435)^2}{435}=1.44$

- (Devil Daggers, Yes): $\frac{(30-39)^2}{39}=2.08$

- (Devil Daggers, No): $\frac{(270-261)^2}{261}=0.31$

- (Icy Tower, Yes): $\frac{(10-26)^2}{26}=9.85$

- (Icy Tower, No): $\frac{(190-174)^2}{174}=1.47$

So, the total $\chi^2$ value is: $\chi^2=9.26+1.44+2.08+0.31+9.85+1.47=24.77$

Interpretation and Properties:

- Range: The $\chi^2$ value is always $\ge 0$. It can never be negative, because all the terms are squared.

- $\chi^2=0$: This would mean that $O=E$ for every single cell. The observed data perfectly matches the ‘independent’ model. This is the worst possible score for feature selection, as it means the feature is $100\%$ independent of the target.

- $\chi^2 > 0$: The larger the $\chi^2$ value, the greater the discrepancy between your observed data and the ‘independent’ model.

- For Feature Selection: We rank our features by their $\chi^2$ score. A higher $\chi^2$ score means the ‘null hypothesis’ (that they are independent) is less likely. This suggests a stronger association/dependency between the feature and target, which makes it a better feature.

In our example, $\chi^2=24.77$ is significantly high, telling us that ‘Video Game’ is almost certainly not independent of ‘Played Game’ and is therefore a good feature to keep.

Variable Applicability:

This is the most important part. The Chi-Squared test operates on counts within discrete categories, so it is applicable when the features are of the following categories:

- $X$: Nominal, Ordinal

- $Y$: Nominal, Ordinal

Nominal, because this is its primary use case. ‘Type’, ‘Country’, ‘Color’, etc. are perfect. Ordinal, because it works perfectly for ordinal data (’Low’, ‘Medium’, ‘High’) as well, because it just treats them as distinct categories. However, it ignores the order information.

You cannot run a $\chi^2$ test on raw continuous variables like ‘Age’ or ‘Price’ because there are no discrete categories to build a contingency table with. Except:, there is a workaround: binning. To use $\chi^2$ with a continuous variable you can first bin it to convert it into an ordinal variable. For example, you could bin ‘Age’ into [’18-30’, ‘31-50’, ‘51+’]. The test is then run on these new bins, not the original data.

Code:

from sklearn.feature_selection import chi2, SelectKBest

# x is a categorical feature in the form of integers

# y is a categorical target

scores, p_values = chi2(X, y)

# you can automatically pick top 5 features

selector = SelectKBest(score_func=chi2, k=5)

X_new = selector.fit_transform(X, y)

Mutual Information (MI)

I hope you’re having fun. If not, you definitely will in this section.

So, we’ve looked at Pearson (linear relationships), Spearman/Kendall (monotonic relationships), and Chi-Squared (independence).

Let me ask you this: what happens when the relationship is weird? For example, what if the relationship is a sine wave? A circle? What if the relationship is “The target is 1 only when $X$ is between $5$ and $10$, otherwise it’s $0$”?

Linear and rank-based approaches will fail here. They might say the correlation is $0$, but the variables are obviously related - just not in a simple straight line.

This is where Mutual Information comes in. MI is a generalist approach to feature selection; it detects any kind of relationship between a feature and a target whether it be linear, non-linear, monotonic, or something really complex. To understand MI and how it works, we first need to go over the concept of Entropy which is a measure of uncertainty.

- Hight Entropy: you have no idea what’s going to happen (you toss a fair coin, and it could be heads or tails with 50/50 probability)

- Low Entropy: you’re pretty sure what’s going to happen (a biased coin that lands on heads with a 90% probability)

- Zero Entropy: you know exactly what will happen (a fraudulent coin with heads on both sides).

Mathematically, the entropy of a variable $Y$ is defined as:

\[H(Y)=-\sum p(y)\log p(y)\]If the formula doesn’t make sense to you, think of the log term as a measure of surprise. For example, if an event is guaranteed $(p=1)$, then $\log(1)=0$. In other words, there is zero surprise, so zero entropy. On the other hand, if an event is rare $(p=0.01)$, the the log value is large — it is surprising.

The formula calculates the weighted average of surprise. We multiple the surprise of an event $\log(p(y))$ by how often that even actually happens $(p(y))$.

Mutual Information answers a simple question: “How much does knowing variable $X$ reduce the uncertainty about variable $Y$?”

Imagine $Y$ is “Will it rain tomorrow?”

Scenario A: I tell you $X=$ “the result of a coin toss I just did”. Does knowing the coin toss result reduce your uncertainty about the rain? I hope not. Therefore, the Mutual Information is 0.

Scenario B: I tell you $X=$ “the humidity level right now”. Does knowing the humidity reduce your uncertainty about the rain? Yes. If humidity is high, you’re more sure it will rain. The Mutual Information is high in this case.

In essence, MI is the intersection of information between two variables. It is the information they share.

Now, let’s move on to the formula. The formula for MI is the total uncertainty of $Y$ minus the uncertainty that remains after knowing $X$. Pretty intuitive, right?

\[I(X;Y)=H(Y)-H(Y|X)\]Let’s dissect this:

-

$H(Y)$ — the initial entropy of your target; in other words, “how hard is it to guess $Y$ without any clues?”.

-

$H(Y|X)$ — the conditional entropy; in other words, “how hard is it to guess $Y$ after I’ve given you the clue $X$?”.

It should now be easy to conclude that if $X$ is a perfect predictor, $H(Y|X)$ becomes $0$ (no uncertainty left), and MI is maximized, or equal to $H(Y)$.

There is also a more formal definition for discrete variables, but I feel like it goes a little too deep into probability theory, so I’m not going to include it here. You’re welcome to take a look at it in Appendix-E though.

Interpretation and Properties:

- Range: $I(X;Y) \ge 0$. Notice that this is different from Correlation. Correlation is always in the range $[-1,1]$. Mutual Information is always non-negative; it starts at $0$ and has no fixed upper bound, although it can be normalized.

- $I(X;Y)=0$: the variables are strictly independent

- Higher values: stronger dependency

If you’re unclear as to when and where to use MI as a metric, maybe this example will help you: Imagine a dataset where points are scattered in a chessboard pattern.

- Pearson’s $r$ will be around $0$ as there is no straight line that fits this dataset

- Spearman’s $\rho$ will also be around $0$ as there is no monotonic trend

- Mutual Information will be high as it will recognize that knowing the $X$ coordinates helps you predict the $Y$ coordinates even if the rule is complex.

So, MI is very versatile, but the calculation method is slightly different depending on your data types. It can be used when your features are of the following categories:

- $X$: Nomina, Ordinal, Interval, Ratio

- $Y$: Nominal, Ordinal, Interval, Ratio

Discrete Data (Nominal/Ordinal) because this is the native habitat of the MI formula ~ you just sum up the probabilities of categories, i.e. $X=$ “color”, $Y=$ “brand”. Continuous Data (Interval/Ratio) because you cannot sum discrete probabilities for continuous numbers like temperature=19.11. However, just like the previous method, you can “chop” the continuous variable into buckets/bins to make it discrete, like $0-10$, $11-20$, etc.

All in all, you can throw almost any data type at Mutual Information, and it will give you a measure of shared information. This makes it one of the best (and my favorite) feature selection methods available.

from sklearn.feature_selection import mutual_info_classif, mutual_info_regression

# for a categorical target:

mi_scores = mutual_info_classif(X, y)

# for a continuous target:

mi_scores = mutual_info_regression(X, y)

print(f"Mutual Information scores: {mi_scores}")

F-Score (ANOVA):

We have covered methods for Categorical data (Chi-Squared) and Continuous (Pearson). But we are missing a very common scenario in ML: classification problems with numerical features.

Let me give you an example I’ve worked on before: imagine you’re building a model to predict whether “Renew their Membership” (Yes/No). You have a feature called “Average Workout Duration”. You aren’t looking for a line of best fit here; you’re looking to see if the workout habits of people who renew are significantly different from those who

This is where ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) and the F-Score come in. In feature selection, the F-score tells us how much a continuous feature “discriminates” between different classes. In other words, it measures how effectively that feature separates the classes by having distinct values for each class. If the “Renew” group works out for 80 minutes on average and the “Quit” group works out for 20 minutes, that feature is a goldmine for your model.

Intuition

To calculate the F-score, we break down the total spread of our data into parts:

- Sum of Squares Between Groups (SSG): This measures the “signal”; that is, it calculates the variation between the group means and the overall average. If this is high, the groups are far apart.

- Sum of Squares Error (SSE): This measures the “noise”; that is, it calculates the variation within each group. If this is high, the data is messy and overlapping, even if the means are different.

The F-score then is the ratio of the variation explalined by the groups to the variation that remains unexplained.

The Math

Before we dive into the formula for the F-score, let me talk about Degrees of Freedom (df). Think of df as the number of “independent pieces of information” available. We use them to average out the Sum of Sauares so that the size of out dataset doesn’t unfairly inflate our score.

- $df_{groups} = (k-1)$: We subtract 1 because if we know the overall mean and the means of $k-1$ goups, the last group’s mean is already determined.

- $df_{error} = (n-k)$: We start with $n$ observations and subtract $k$ because we had to calculate $k$ different group means to find the error.

By dividing the Sum of Squares by their respective df, we get the Mean Squares:

\[\begin{aligned} MSG = \frac{SSG}{k-1} \; \; (Mean Square Groups) \\\\ MSE = \frac{SSE}{n-k} \; \; (Mean Square Error) \end{aligned}\]Finally, just like I pointed out, the F-score is the ratio of these two:

\[F = \frac{MSG}{MSE}\]In the context of feature selection, if we get a high F-score, the Signal (difference between groups) is much larger than the noise (variance within groups). So we should probably use this feature. On the other hand, if the signal and noise are about the same, the feature is likely useless for distinguishing between your classes.

Application

ANOVA F-score is applicable when:

- $X$: Continuous (Interval/Ratio)

- $Y$: Categorical (Nominal/Ordinal)

The F-score starts at 0 and can go quite high.

Here’s the implementation in Python:

from sklearn.feature_selection import f_classif, SelectKBest

import pandas as pd

# X = [Duration, Age, Monthly_Fee], y = [Renew_Status]

# f_classif calculates the F-score for each feature

f_scores, p_values = f_classif(X, y)

# you can create a simple selector to pick the top 2 features

selector = SelectKBest(score_func=f_classif, k=2)

X_new = selector.fit_transform(X, y)

print(f"Selected features based on highest F-scores!")

Point-Biserial Correlation: $(r_{pb})$

Finally, let’s end our tour with a very specific, high-precision tool: Point-Biserial Correlation.

We just looked at the ANOVA F-Score, which handles “Categorical vs Numerical” data. Point-Biserial is a specialized cousin of that method designed for the case when the categorical variable is Binary (i.e. has exactly two categories). For example:

- $X$: “Salary” (numerical) vs $Y$: “Owns a BMW (Yes/No)” (binary)

- $X$: “Blood pressure” (numerical) vs $Y$: “Has heard disease (True/False)” (binary)

While ANOVA tells you if the groups are different, Point-Biserial tells you how they are different (with strength and direction) relative to the binary outcome.

Intuition

The intuition here is similar to the F-score but simpler. We are comparing the mean of the continuous variable for Group 0 agains the mean for Group 1.

- If the mean of Group 1 is much higher than the mean of Group 0, we have a positive relationship.

- If the mean of Group 1 is much lower, we have a negative relationship.

- If the means are the same, the variable provides no information; the correlation is 0.

The formula for Point-Biserial Correlation $(r_{rb})$ is surprisingly elegant. It combines the difference in means with the proportion of samples in groups.

\[r_{pb}=\frac {\mu_1-\mu_0} {\sigma_x}\sqrt{p\cdot q}\]Let’s look at the formula a bit closer:

- $\mu_1$: The mean value of the continuous variable for all data points in Group 1.$\;$

- $\mu_0$: The mean value of the continuous variable for all data points in Group 0.$\;$

- $\sigma_x$: The standard deviation of the continuous varaible (calculated for the whole dataset)$.$

- $p$: The proportion of data points that belong to Group 0. Note that $q=1-p$

The Logic:

- $\frac{\mu_1-\mu_0}{\sigma_x}$: This is the Effect Size. It asks: How many standard deviations apart are the two groups?

- $\sqrt{p\cdot q}$: This is a weighing factor. The correlaiton is strongest when the groups are balanced $(p=0.5, q=0.5)$. If one group is extremely rare, for example $p=0.01$, it’s harder to claim a strong correlation across the whole dataset, and this term shrinks the result.

Here’s what might be helpful for you to understand this metric even better: Point-Biserial Correlation is mathematically equivalent to Pearson’s $r$. If you take your binary labels (e.g. “yes”, “no”) and convert them into numbers (1, 0) and then simplify the run for the standard Person’s correlation formula on that data, you’ll get exactly the same number as the Point-Biserial formula above. Two points on this:

So why does this specific formula exist? Because, before computers were powerful, calculating Person’s $r$ on thousands of rows was tedious. The $r_{pb}$ formula provided a computational shortcut because you only need the group means and the proportions, which were much faster to calculate by hand. Today, we distinguish it mostly to be precise about our data types, but mathematically, it’s just Pearson.

Interpretation and Properties:

- Range: $-1\le r_{pb}\le1$.

- Positive Value: High values of the continuous variable are associated with Category 1.

- Negative Value: High values of the continuous variable are associated with Category 0.

- Zero: There is no difference in the means of the two groups.

Point-Biserial vs ANOVA:

ANOVA checks if means differ, but the resulting F-score is always positive. It doesn’t tell you which group is higher, just that they’re different. Point-Biserial, on the other hand,gives you the sign (positive/negative), telling you the direction of the relationship.

The method is strict about the categorical side. It is applicable when the features are of the following categories:

- $X$: Interval, Ratio (Continuous)

- $Y$: Binary Nominal (Must have exactly two categories)

If $Y$ has 3+ categories (e.g. ‘red’, ‘green’, ‘blue’), you cannot assign them 0 and 1. You cannot subtract $\mu_{red}-\mu_{green}-\mu_{blue}$. The formula breaks, and you should switch to ANOVA.

In the context of feature selection, imagine again that you are predicting whether a loan will default (Default = Yes/No) and are evaluating a feature like debt-to-income ratio. Computing the point-biserial correlation tells you whether borrowers who default tend to have higher or lower debt-to-income ratios, and how strong that separation is. A large magnitude shows the feature is informative on its own, while a value near zero shows little contribution, so you can probably get rid of it.

from scipy.stats import pointbiserialr

# x: Continuous feature

# y: Binary target (0s and 1s)

corr, p_value = pointbiserialr(y, x)

print(f"Point-Biserial Correlation: {corr:.3f}")

print(f"P-value: {p_value:.3e}")

Summary

I hope you learned something new from this guide and that it will be useful when you’re tackling your own ML problem one day. If there is one takeaway from all these methods, it’s this: Context is King.

There is no best feature to selection method. There is only the method that fits the right shape and type of your data. For instance, using Pearson’s $r$ on complex, non-linear data is like trying to measure the volume of a sphere using a ruler. You will get a number, but it won’t be the right one.

As you build your feature selection pipeline, your first step should always be to identify the data types of your Feature $X$ and Target $Y$. Once you know that, you can use the table below to prick the mathematically correct tool for the job.

| Method | Variable $X$ (feature) | Variable $Y$ (target) | Relationship Type | Intuition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s $r$ | Continuous | Continuous | Linear | Measures how well a straight line fits the data |

| Spearman/Kendall | Ordinal/Continuous | Ordinal/Continuous | Monotonic | Measures if $Y$ increases as increases (even if not in a straight line) |

| Chi-Squared | Categorical | Categorical | Dependency | Comparing “Observed” counts vs “Expected” counts to find dependency |

| ANOVA F-Score | Continuous | Categorical (2+) | Difference in Means | Checks if the groups are distinctly separated by the feature |

| Point-Biserial | Continuous | Binary (0/1) | Difference in Means | Same as ANOVA but gives direction (+ or -) for binary targets |

| Mutual Information | Any | Any | Any (complex) | Measures how much “uncertainty” about $Y$ is removed by knowing $X$. Catches non-linear/complexpatterns. |

Appendix

A — Expectation

The expectation is a numerical measure that summarizes the typical, or average, behavior of a random variable. If $X$ is a random variable that takes on discrete numeric values in a set $S$, its expectation is defined as:

\[E[X]=\sum_{x \in S}xP(X=x)\](The sum of every value multiplied by the probability of observing that value)

In other words, expectation is a weighted average of the values of $X$, where the weights are the corresponding probabilities of those values. The expectation places more weight on values that have greater probability.

As an example, let’s say a shop sells three pens $A, B,C$ at $\$1,\$2,$ and $\$3$, respectively. I, having found a new hobby of writing blogs, want to pick one of these pens at random. Let $X$ be the price of the pen that I pick and $S={1,2,3}$ the set of prices. What is the expected price of the pen I pick at random?

We can answer this question using the formula for the expectation. Since I uniformly choose one of the three pens at random, the probability of getting each price is the same:

\[P(X=1)=P(X=2)=P(X=3)=\frac{1}{3}\]Using the definition,

\[E[X]=\sum_{x \in S}xP(X=x)=1\cdot\frac{1}{3}+ 2\cdot\frac{1}{3} + 3\cdot\frac{1}{3}=2\]This means that if I repeated the experiment of randomly visiting the shop and randomly picking one of the three pens, the ‘typical’ or ‘average’ price I can expect to pay is $$2$. Also, note that since we’re working in a uniform setting (that is the probability of each outcome is the same), the expectation becomes the same as the arithmetic mean.

B — Variance and Standard Deviation

Variance and Standard Deviation are measures of variability or spread. They describe how near or far the typical typical outcomes are to the expected value. If you understand what the Expected value is, then variance and SD should be much easier to understand.

Let’s again assume that $X$ is a discrete random variable over a set $S$ with mean $\mu$. The formula for its variance is

\[V[X]=E[(X-\mu)^2]=\sum_{x \in S} (x-\mu)^2P(X=x)\](The sum of the squared differences between each value and the mean multiplied by the probability of observing that value)

As you may be able to tell, the formulas for variance and expectation are the same except for the fact that variance is the weighted sum of the squared differences between the mean and the values in $S$ as opposed to the weighted sum of those values alone. So it should be clear that variance is a function of expectation and measures the typical squared difference from the mean. The standard deviation is just the squared root of the variance, which makes it the measure of a typical difference from the mean:

\[SD[X]=\sqrt{V[X]}\]C — The Range of Pearson’s R

Given a random variable with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$, the standardized variable $X^*$ is defined as

\[X^*=\frac{X-\mu}{\sigma}\]Observe that

\[E[X^*]=E[\frac{X-\mu}{\sigma}]= \frac{1}{\sigma}(E[X]-\mu)= \frac{1}{\sigma}(\mu-\mu)=0\] \[V[X^*]=V[\frac{X-\mu}{\sigma}]= \frac{1}{\sigma^2}(V[X-\mu])= \frac{\sigma^2}{\sigma^2}=1\]For random variables $X$ and $Y$,

\[-1\leq Corr(X,Y)\leq 1\]If $Corr(X,Y)= \pm 1$, then there exists constants $a \neq 0$ and $b$ such that $Y=aX+b$.

Proof: Given $X$ and $Y$, let $X^$ and $Y^$ be the standardized variables. Observe that

\[Cov(X^*,Y^*) =Cov(\frac{X-\mu_X}{\sigma_X},\frac{Y-\mu_Y}{\sigma_Y})= \frac{1}{\sigma_X \sigma_Y}Cov(X,Y)= Corr(X,Y)\]Consider the variance of $X^\pm Y^$:

\[V[X^*+Y^*]=V(X^*)+V(Y^*)+2Cov(X^*,Y^*) \newline =2+2Corr(X,Y)\]similarly,

\[V[X^*-Y^*]=V(X^*)+V(Y^*)-2Cov(X^*,Y^*) \newline =2-2Corr(X,Y)\]This gives,

\[Corr(X,Y)=-\frac{V(X^*-Y^*)}{2}+1\leq-1\]because the variance is nonnegative. That is, $-1\leq Corr(X,Y)\leq1$.

D — Geometric Mean

The geometric mean of $n$ numbers $x_1,x_2,\dots,x_n$ is expressed as

\[(x_1 x_2\dots x_n)^{1/n}\]If you have values, like 2 and 8, their arithmetic mean is $(2+8)/2=5$ and geometric mean is $\sqrt{2\cdot 8}=4$. Notice 4 is closer to the smaller number. That’s because the geometric mean balances rations but not differences, that’s why it’s symmetric on a multiplicative scale: $2:4=4:8$ both sides scale by a factor of 2.

In Tau-b’s denominator, we have two scales of comparison:

\[A=(N_c+N_d+T_x)\newline B=(N_c+N_d+T_y)\]Each tells you how many usable pairs exist if you ignore ties for $x$ or for $y$. But $A$ and $B$ might not be equal, and $x$ and $y$ could have different numbers of ties. So we want t single denominator that is fair to both (is symmetric), reflects proportional balance between them, and doesn’t overly favor the one with more ties; so instead of averaging them, we take their geometric mean.

This way, if one variable has lots of ties (small $A)$, it pulls the denominator down proportionally. If both have many ties, both shrink it. If ties are the same, the denominator is just $A$ (or $B$).

This multiplicative balance keeps $\tau_B$ bounded between $-1$ and $+1$.

E — Mutual Information for Discrete Variables

For discrete variables, the Mutual Information formula looks like this:

\[I(X;Y)=\sum_{x\in X}\sum_{y \in Y} p(x,y) \log [ \frac {p(x, y)} {p(x)p(y)} ]\]What this formula does is it compares the joint probability $p(x,y)$ - what we actually see - with the product of the marginal probabilities $p(x)p(y)$ - what we would expect if they were independent.

- If $X$ and $Y$ are independent, $p(x,y) \approx p(x)p(x)$

- The log of $1$ is $0$

- So, $I(X;Y)=0$