To keep things computationally simple, we are going to use a binomial model for the price of the underlying Nvidia stock. We don’t know the daily volatility, so we’ll keep that as a variable we call \(\sigma\). We will pretend that each day, the Nvidia stock price can either grow with a factor of \(e^\sigma\) or shrink with a factor of \(e^{-\sigma}\).5 This is a geometric binomial walk. We could transform everything in the reasoning below with the logarithm and get an additive walk in log-returns.

Thus, on day zero, the Nvidia stock trades for $184. On day one, it can take one of two values:

- \(184e^\sigma\) because it went up, or

- \(184e^{-\sigma}\) because it went down.

On day two, it can have one of three values:

- \(184e^{2\sigma}\) (went up both in the first and second day),

- \(184e^{\sigma - \sigma} = 184\) (went up and then down, or vice versa), or

- \(184e^{-2\sigma}\) (went down both days).

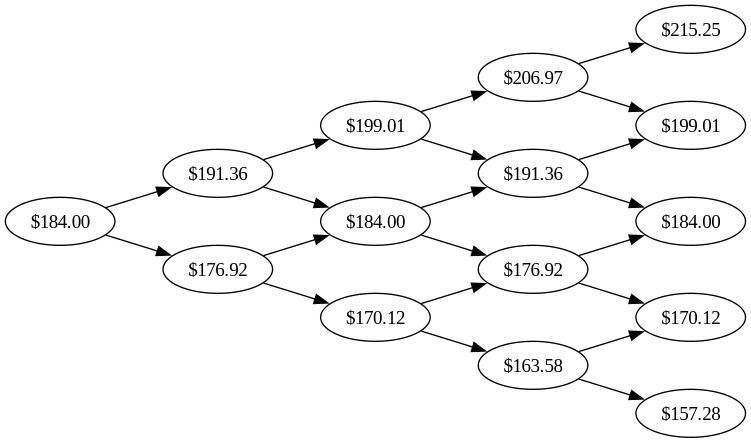

If it’s easier, we can visualise this as a tree. Each day, the stock price branches into two possibilities, one where it rises, and one where it goes down. In the graph below, each column of bubbles represents the closing value for a day.

This looks like a very crude approximation, but it actually works if the time steps are fine-grained enough. The uncertainties involved in some of the other estimations we’ll do dwarf the inaccuracies introduced by this model.6 Even for fairly serious use, I wouldn’t be unhappy with daily time steps when the analysis goes a year out.

It is important to keep in mind that the specific numbers in the bubbles depend on which number we selected for the daily volatility \(\sigma\). Any conclusion we draw from this tree is a function of the specific \(\sigma\) chosen to construct the tree.

When we have chosen an initial \(\sigma\) and constructed this tree, we can price an option using it. Maybe we have a call option expiring on day three, with a strike price of $180. On day four, the last day, the option has expired, so it is worth nothing. We’ll put that into the tree.

We have already seen what the value of the option is on the day it expires: it’s what we would profit from exercising it. If the stock is valued at $191, the option is worth $11, the difference between the stock value and the strike price. On the other hand, if the stock is valued at $177, it is worth less than the strike price of the option, so we will not exercise the option, instead letting it expire.

The day before the expiration day is when we have the first interesting choice to make. We can still exercise the option, with the exercise value of the option calculated the same way.

Or we could hold on to the option. If we hold on to the option for a day, the value of the option will either go up or down, depending on the value of the underlying stock price. We will compute a weighted average of these movement possibilities as

\[\tilde{p} V_u + (1 - \tilde{p}) V_d\]

where \(V_u\) and \(V_d\) are the values the option will have on the next day when the underlying moves up or down in the tree, respectively. Then we’ll discount this with a safe interest rate to account for the fact that by holding the option, we are foregoing cash that could otherwise be used to invest elsewhere. The general equation for the hold value of the option at any time before the expiration day is

\[e^{-r} \left[ \tilde{p} \; V_u + (1 - \tilde{p}) V_d \right].\]

Let’s look specifically at the node where the stock value is $199. We’ll assume a safe interest rate of 3.6 % annually, which translates to 0.01 % daily.7 In the texts I’ve read, 4 % is commonly assumed, but more accurate estimations can be derived from us Treasury bills and similar extremely low-risk interest rates. The value of holding on to the option is, then

\[0.9999 \left[ \tilde{p} \; 26.97 + (1 - \tilde{p}) 11.36 \right]\]

and now we only need to know what \(\tilde{p}\) is. That variable looks and behaves a lot like a probability, but it’s not. There’s an arbitrage argument that fixes the value of \(\tilde{p}\) to

\[\tilde{p} = \frac{e^r - e^{-\sigma}}{e^\sigma - e^{-\sigma}}\]

where \(\sigma\) is the same time step volatility we assumed when creating the tree – in our case, 4 %. This makes \(\tilde{p} = 0.491\), and with this, we can compute the hold value of the option when the underlying is $199:

- Hold value: $19.03

- Exercise value: $19.01

The value of the option at any point in time is the maximum of the hold value and the exercise value. So we replace the stock value of $199 in the tree with the option value of $19.03. We perform the same calculation for the other nodes in day two.

and then we do the same for the day before that, then before that, etc., until we get to day zero.

We learn that if someone asks us on day zero to buy a call option with a strike price of $180 and expiry three days later, when the underlying stock currently trades for $184, and has an expected daily volatility of 0.04, then we should be willing to pay $7.38 for that option.

What’s weird is this number has nothing to do with the probability we are assigning to up or down movements. Go through the calculations again. We never involved any probability in the calculation of the price. Although I won’t go through the argument – see Shreve’s excellent Stochastic Calculus for Finance8 Stochastic Calculus for Finance I: The Binomial Asset Pricing Model; Shreve; Springer; 2005. for that – this price for the option is based on what it would cost to hedge the option with a portfolio of safe investments, borrowing, and long or short positions in the underlying stock.

Even without going through the detailed theory, we can fairly quickly verify that this is indeed how options are priced. Above, we made educated guesses as to the safe interest rate, a reasonable volatility, etc. We calculated with a spot price of $184, a strike price of $180, and expiry three days out. We got an option price of $7.38.

At the time of writing, the Nvidia stock trades at $184.94. It has options that expire in four days. The ones with a strike price of $180 currently sell for $6.20. That’s incredibly close, given the rough estimations and the slight mismatch in duration.9 The main inaccuracy comes from the volatility we used to construct the tree. The actual volatility of the Nvidia stock on such short time periods and small differences in price is lower.