or, designing AI apps with a sense of taste

How do you turn a freeform query like ‘sfo-jfk’ into a beautiful image?

This was a real problem I to solve recently. Whenever our users create a trip, we find a beautiful photo of their destination and present it to them. To do this, we need a system that could understand anything, and respond with a hand-curated photo.

To solve this, I used LLMs for understanding, traditional software engineering in the middle, and human curation (by me) of photos by excellent (human) photographers. By walking through this, I hope to provide some inspiration for how to use LLMs in ways that feel crafted and not like slop!

The problem

I work on Stardrift, an AI travel planning app, and we let people type whatever they want into a chatbox. But then we need to turn that into a beautiful homepage of images for them:

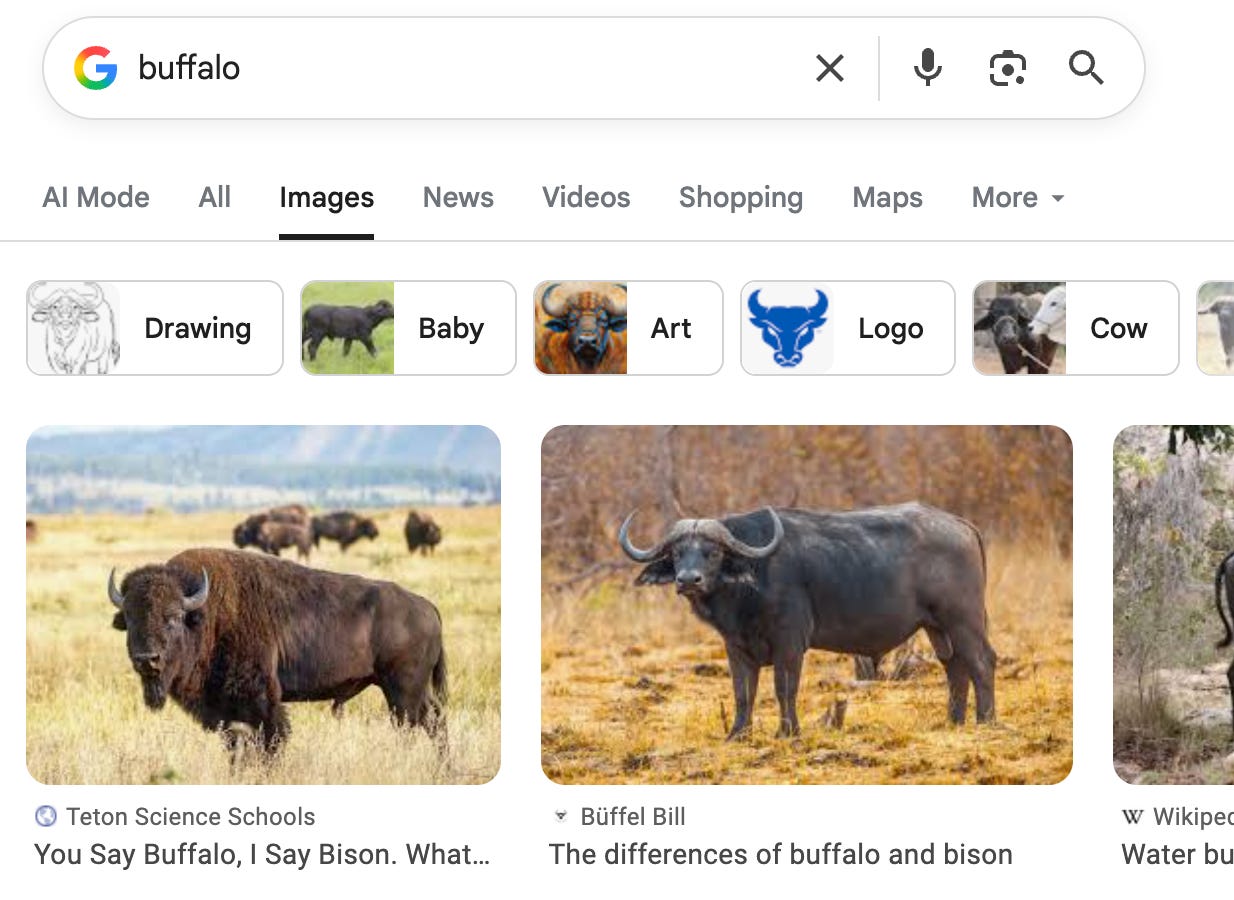

Here are some silly ideas for how you could solve this. You could AI-generate an image for each conversation. But AI-generated images suck, and it’s expensive. You could Google search the destination – but that has copyright issues, and some risks:

Ultimately, what I wanted to do was hand-curate a beautiful mapping from ‘location’ to ‘destinations’. And I wanted to match a query that could be about literally anything to this.

If you break this problem down, there are effectively three problems here:

- Take a freeform query (like ‘sfo->jfk’) and turn it into a ‘place’

- Build a database of ‘places’ -> pictures

- Build a software system that can take a ‘place’, look it up in a database and spit out the right picture – even if that ‘place’ isn’t in the database

To explain how I built this, I’ll run through each step-by-step.

1. What is a place?

This was the simplest part of the project, from a technical perspective – and also the trickiest to design.

Nowadays, you can easily run a query like ‘SFO-JFK tomorrow’ through an LLM like Haiku and ask it to tell you where they’re going. Which is really cool – 5 years ago, this would have been impossible!

However, I had to be careful about what exactly I asked it for. If you think about it, a query like “SFO-JFK” should return “New York.” But “plan me a road-trip around the Isle of Skye” should return a picture of the “Isle of Skye”, not a generic picture of Scotland.

To add to the complication, very often our users mention multiple places in one chat — they might be going on a honeymoon trip through France, Germany and Belgium. We need to capture all of this.

After thinking a bit, I decided we’d build the system around this idea of a ‘place’. I decided that every query could give us a list of places, and every place would be a combination of a ‘name’ (e.g. New York), and a type of place (e.g. city/region/country).

So when the LLM is given “sfo-jfk,” it returns “the city, New York”. “Plan me a 3-day road trip around the Isle of Skye” will return “Isle of Skye, the region”. And if you ask about multiple places, we return a list. This sounds a bit dry and technical — and it is — but it was important to make the rest work.

For the programmers, here’s the base datatype I ended up with:

class Place:

type: Union["region" | "city" | "country"]

name: str

def query_to_place(query: str) -> list[Place]:

...2. Build a mapping of ‘places’ -> pictures

Now that I had a definition of a ‘place’ defined, I could start creating my database of pictures.

This part was the most fun. I ran this new function I’d written to map queries to places on a sample of real Stardrift queries, which gave me a list of places ranked by popularity.

Then I wrote a little game.

We source pictures from Unsplash, a fantastic photography bank. Unsplash has an API, so I wrote an internal tool that went through this ranked list of locations and pulled the top 5 images from Unsplash. This let me pick the best one, and it would be saved into a database:

Because of some API restrictions, I could only do about 20 places per hour. So while it only took me an afternoon to code the rest of the system, it took about 3 days to populate the database with the first 500 places, done mostly in 5-minute chunks every hour. But it was worth it – the game was very fun, and the mapping we produced is beautiful!

3. Putting it together

Now I could turn a conversation into a ‘place’, and had a database mapping ‘places’ to beautiful photos.

But our users could ask about anything, and our LLM would simply pass on whatever it said. To add insult to injury, our LLM wasn’t very precise — sometimes it would tell us the user was going to ‘NYC’, sometimes ‘New York’, sometime ‘New York City’. So how I meant to handle places that didn’t have an entry in the database?

Well, thanks to Google Maps, it’s very easy to turn any place name into latitude/longitude coordinates. So whenever we got weird input, we could turn it into a coordinate. And then we could ask: what’s the closest place that we do have in the database?

For instance, we might get a place like ‘Deadvlei.’ I have no idea where that is. But our geolocation API tells us it’s at (24.7° S, 15.2° E), so we can lookup to the closest coordinate that’s in the database, which is (24.8° S, 15.3° E). Then we can return the nearest one: in this case, Namibia:

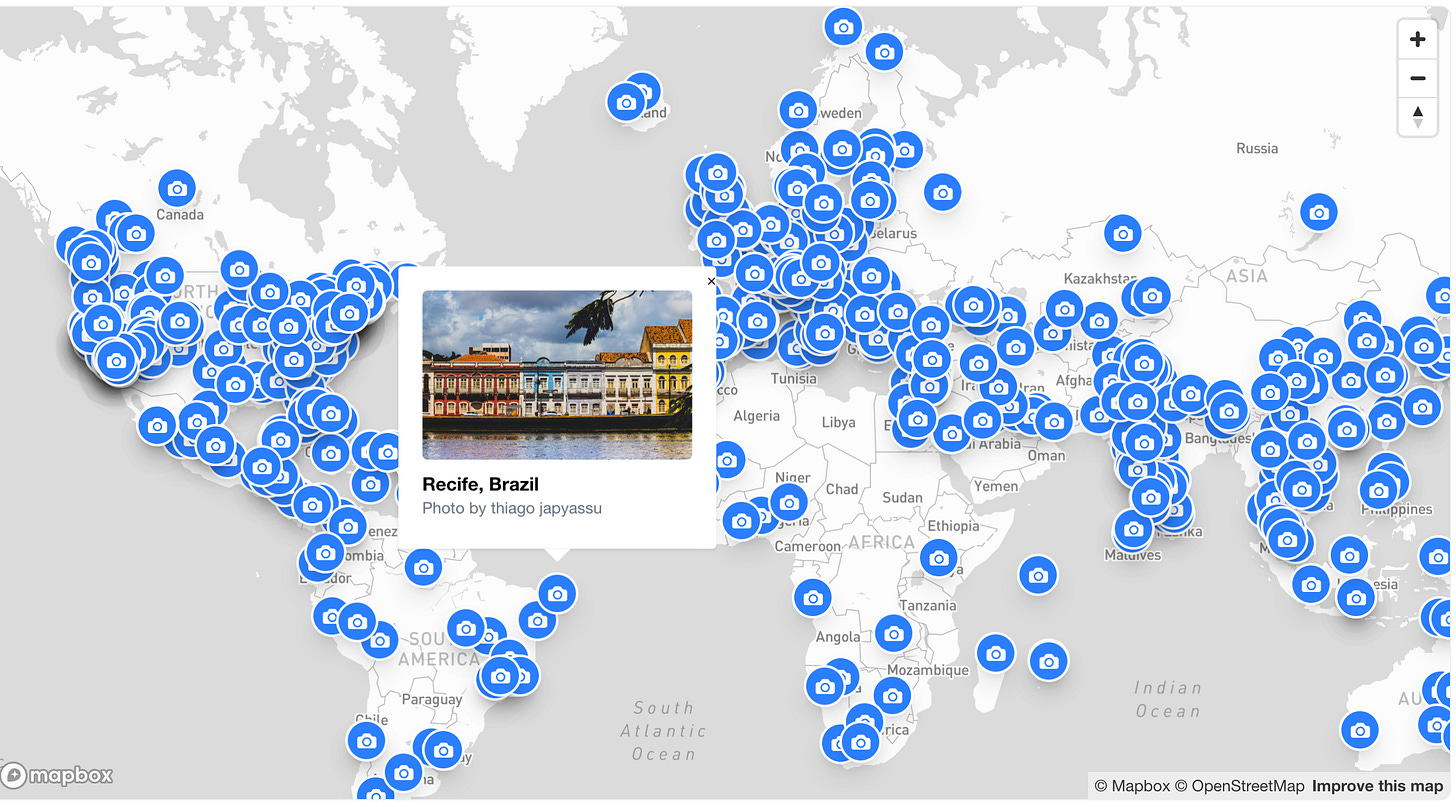

This mostly works, but it does mean there are a few places that don’t properly show up! One of the last tools I built was a little map that showed us where we have photos, so I could see where we had gaps. It turned out we were missing a lot of Africa and South America — they are not common travel destinations. So I manually filled them in.

We have missed places since — recently someone tried to search ‘Mongolia,’ which we didn’t have. When this happens, it sets off an alert to us, and then I manually go in and backfill it. It works well enough.

Final thoughts

There are some flaws to this system: for instance, we have a lot of cities mapped but not a lot of regions, so you might search for ‘The Gold Coast’ and get a photo of Brisbane instead. And everything is subject to my taste—my team recently made fun of me for always picking golden hour photos. (Wait, maybe that’s a feature...)

But I like it as a small but tasteful AI project. The best AI products don’t use AI for everything; they use it for what it’s good at. And that’s exactly what we did here, mixing software engineering, AI engineering and a bit of good old human curation.

This is a cross-post from the Stardrift technical blog! Shoutout to Sarah Chieng and swyx for hosting the Write & Learn meetup where I wrote this.