AI companies are being priced into the hundreds of billions. That forces one awkward question to the front: do the unit economics actually work?

Jevons’ paradox suggests that as tokens get cheaper, demand explodes. You’ve likely felt some version of this in the last year. But as usage grows, are these models actually profitable to run?

In our collaboration with Epoch AI, we tackle that question using OpenAI’s GPT-5 as the case study. What looks like a simple margin calculation is closer to a forensic exercise: we triangulate reported details, leaks, and Sam Altman’s own words to bracket plausible revenues and costs.

Here’s the breakdown.

— Azeem

Originally published on Epoch AI’s blog. Analysis by Jaime Sevilla, Exponential View’s Hannah Petrovic, and Anson Ho

Are AI models profitable? If you ask Sam Altman and Dario Amodei, the answer seems to be yes — it just doesn’t appear that way on the surface.

Here’s the idea: running each AI model generates enough revenue to cover its own R&D costs. But that surplus gets outweighed by the costs of developing the next big model. So, despite making money on each model, companies can lose money each year.

This is big if true. In fast-growing tech sectors, investors typically accept losses today in exchange for big profits down the line. So if AI models are already covering their own costs, that would paint a healthy financial outlook for AI companies.

But we can’t take Altman and Amodei at their word — you’d expect CEOs to paint a rosy picture of their company’s finances. And even if they’re right, we don’t know just how profitable models are.

To shed light on this, we looked into a notable case study: using public reporting on OpenAI’s finances, we made an educated guess on the profits from running GPT-5, and whether that was enough to recoup its R&D costs. Here’s what we found:

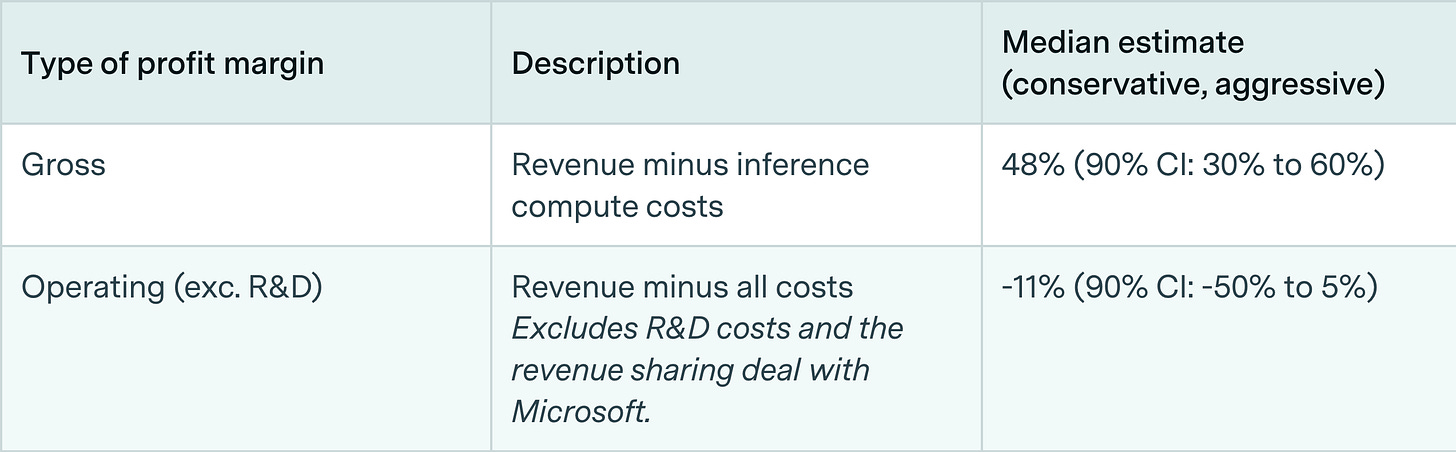

Whether OpenAI was profitable to run depends on which profit margin you’re talking about. If we subtract the cost of compute from revenue to calculate the gross margin (on an accounting basis), it seems to be about 50% — lower than the norm for software companies (where 60-80% is typical) but still higher than many industries.

But if you also subtract other operating costs, including salaries and marketing, then OpenAI most likely made a loss, even without including R&D.

Moreover, OpenAI likely failed to recoup the costs of developing GPT-5 during its 4-month lifetime. Even using gross profit, GPT-5’s tenure was too short to bring in enough revenue to offset its own R&D costs. So if GPT-5 is at all representative, then at least for now, developing and running AI models is loss-making.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that models like GPT-5 are a bad investment. Even an unprofitable model demonstrates progress, which attracts customers and helps labs raise money to train future models — and that next generation may earn far more. What’s more, the R&D that went into GPT-5 likely informs future models like GPT-6. So these labs might have a much better financial outlook than it might initially seem.

Let’s dig into the details.

To answer this question, we consider a case study which we call the “GPT-5 bundle”. This includes all of OpenAI’s offerings available during GPT-5’s lifetime as the flagship model — GPT-5 and GPT-5.1, GPT-4o, ChatGPT, the API, and so on. We then estimate the revenue and costs of running the bundle.

Revenue is relatively straightforward: since the bundle includes all of OpenAI’s models, this is just their total revenue over GPT-5’s lifetime, from August to December last year. This works out to $6.1 billion.

At first glance, $6.1 billion sounds healthy, until you juxtapose it with the costs of running the GPT-5 bundle. These costs come from four main sources:

Inference compute: $3.2 billion. This is based on public estimates of OpenAI’s total inference compute spend in 2025, and assuming that the allocation of compute during GPT-5’s tenure was proportional to the fraction of the year’s revenue raised in that period.

Staff compensation: $1.2 billion, which we can back out from OpenAI staff counts, reports on stock compensation, and things like H1B filings. One big uncertainty with this: how much of the stock compensation goes toward running models, rather than R&D? We assume 40%, matching the fraction of compute that goes to inference. Whether staffing follows the same split is uncertain, but it’s our best guess.

Sales and marketing (S&M): $2.2 billion, assuming OpenAI’s spending on this grew between the first and second halves of last year.

Legal, office, and administrative costs: $0.2 billion, assuming this grew between 1.6× and 2× relative to their 2024 expenses. This accounts for office expansions, new office setups, and rising administrative costs with their growing workforce.

So what are the profits? One option is to look at gross profits. This only counts the direct cost of running a model, which in this case is just the inference compute cost of $3.2 billion. Since the revenue was $6.1 billion, this leads to a profit of $2.9 billion, or gross profit margin of 48%, and in line with other estimates. This is lower than other software businesses (typically 70-80%) but high enough to eventually build a business on.

On the other hand, if we add up all four cost types, we get close to $6.8 billion. That’s somewhat higher than the revenue, so on these terms the GPT-5 bundle made an operating loss of $0.7 billion, with an operating margin of -11%.

Stress-testing the analysis with more aggressive or conservative assumptions doesn’t change the picture much:

And there’s one more hiccup: OpenAI signed a deal with Microsoft to hand over about 20% of their $6.1 billion revenue, making their losses even larger still. This doesn’t mean that the revenue deal is entirely harmful to OpenAI — for example, Microsoft also shares revenue back to OpenAI. And the deal probably shouldn’t significantly affect how we see model profitability — it seems more to do with OpenAI’s economic structure rather than something fundamental to AI models. But the fact that OpenAI and Microsoft have been renegotiating this deal suggests it’s a real drag on OpenAI’s path to profitability.

In short, running AI models is likely profitable in the sense of having decent gross margins. But OpenAI’s operating margin, which includes marketing and staffing, is likely negative. For a fast-growing company, though, operating margins can be misleading — S&M costs typically grow sublinearly with revenue, so gross margins are arguably a better proxy for long-run profitability.

So our numbers don’t necessarily contradict Altman and Amodei yet. But so far we’ve only seen half the story — we still need to account for R&D costs, which we’ll turn to now.

Let’s say we buy the argument that we should look at gross margins. On those terms, it was profitable to run the GPT-5 bundle. But was it profitable enough to recoup the costs of developing it?

In theory, yes — you just have to keep running them, and sooner or later you’ll earn enough revenue to recoup these costs. But in practice, models might have too short a lifetime to make enough revenue. For example, they could be outcompeted by products from rival labs, forcing them to be replaced.

So to figure out the answer, let’s go back to the GPT-5 bundle. We’ve already figured out its gross profits to be around $3 billion. So how do these compare to its R&D costs?

Estimating this turns out to be a finicky business. We estimate that OpenAI spent $16 billion on R&D in 2025, but there’s no conceptually clean way to attribute some fraction of this to the GPT-5 bundle. We’d need to make several arbitrary choices: should we count the R&D effort that went into earlier reasoning models, like o1 and o3? Or what if experiments failed, and didn’t directly change how GPT-5 was trained? Depending on how you answer these questions, the development cost could vary significantly.

But we can still do an illustrative calculation: let’s conservatively assume that OpenAI started R&D on GPT-5 after o3’s release last April. Then there’d still be four months between then and GPT-5’s release in August, during which OpenAI spent around $5 billion on R&D. But that’s still higher than the $3 billion of gross profits. In other words, OpenAI spent more on R&D in the four months preceding GPT-5, than it made in gross profits during GPT-5’s four-month tenure.

So in practice, it seems like model tenures might indeed be too short to recoup R&D costs. Indeed, GPT-5’s short tenure was driven by external competition — Gemini 3 Pro had arguably surpassed the GPT-5 base model within three months.

One way to think about this is to treat frontier models like rapidly-depreciating infrastructure: their value must be extracted before competitors or successors render them obsolete. So to evaluate AI products, we need to look at both profit margins in inference as well as the time it takes for users to migrate to something better. In the case of the GPT-5 bundle, we find that it’s decidedly unprofitable over its full lifecycle, even from a gross margin perspective.

So the finances of the GPT-5 bundle are less rosy than Altman and Amodei suggest. And while we don’t have as much direct evidence on other models from other labs, they’re plausibly in a similar boat — for instance, Anthropic has reported similar gross margins to OpenAI. So it’s worth thinking about what it means if the GPT-5 bundle is at all representative of other models.

The most crucial point is that these model lifecycle losses aren’t necessarily cause for alarm. AI models don’t need to be profitable today, as long as companies can convince investors that they will be in the future. That’s standard for fast-growing tech companies.

Early on, investors value growth over profit, believing that once a company has captured the market, they’ll eventually figure out how to make it profitable. The archetypal example of this is Uber — they accumulated a $32.5 billion deficit over 14 years of net losses, before their first profitable year in 2023. By that measure, OpenAI is thriving: revenues are tripling annually, and projections show continued growth. If that trajectory holds, profitability looks very likely.

And there are reasons to even be really bullish about AI’s long-run profitability — most notably, the sheer scale of value that AI could create. Many higher-ups at AI companies expect AI systems to outcompete humans across virtually all economically valuable tasks. If you truly believe that in your heart of hearts, that means potentially capturing trillions of dollars from labor automation. The resulting revenue growth could dwarf development costs even with thin margins and short model lifespans.

That’s a big leap, and some investors won’t buy the vision. Or they might doubt that massive revenue growth automatically means huge profits — what if R&D costs scale up like revenue? These investors might pay special attention to the profit margins of current AI, and want a more concrete picture of how AI companies could be profitable in the near term.

There’s an answer for these investors, too. Even if you doubt that AI will become good enough to spark the intelligence explosion or double human lifespans, there are still ways that AI companies could turn a profit. For example, OpenAI is now rolling out ads to some ChatGPT users, which could add between $2 to 15 billion in yearly revenue even without any user growth. They’re moving beyond individual consumers and increasingly leaning on enterprise adoption. Algorithmic innovations mean that running models could get many times cheaper each year, and possibly much faster. And there’s still a lot of room to grow their user base and usage intensity — for example, ChatGPT has close to a billion users, compared to around six billion internet users. Combined, these could add many tens of billions of revenue.

It won’t necessarily be easy for AI companies to do this, especially because individual labs will need to come face-to-face with AI’s “depreciating infrastructure” problem. In practice, the “state-of-the-art” is often challenged within months of a model’s release, and it’s hard to make a profit from the latest GPT if Claude and Gemini keep drawing users away.

But this inter-lab competition doesn’t stop all AI models from being profitable. Profits are often high in oligopolies because consumers have limited alternatives to switch to. One lab could also pull ahead because they have some kind of algorithmic “secret sauce”, or they have more compute. Or they develop continual learning techniques that make it harder for consumers to switch between model providers.

These competitive barriers can also be circumvented. Companies could form their own niches, and we’ve already seen that to some degree: Anthropic is pursuing something akin to a “code is all you need” mission, Google DeepMind wants to “solve intelligence” and use that to solve everything from cancer to climate change, and Meta strives to make AI friends too cheap to meter. This lets individual companies gain revenue for longer.

So will AI models (and hence AI companies) become profitable? We think it’s very possible. While our analysis of the GPT-5 bundle is more conservative than Altman and Amodei hint at, what matters more is the trend: Compute margins are falling, enterprise deals are stickier, and models can stay relevant longer than the GPT-5 cycle suggests.

Authors’ note: We’d like to thank JS Denain, Josh You, David Owen, Yafah Edelman, Ricardo Pimentel, Marija Gavrilov, Caroline Falkman Olsson, Lynette Bye, Jay Tate, Dwarkesh Patel, Juan García, Charles Dillon, Brendan Halstead, Isabel Johnson and Markov Gray for their feedback and support on this post. Special thanks to Azeem Azhar for initiating this collaboration and vital input, and Benjamin Todd for in-depth feedback and discussion.