The Coleco Adam computer was a 1983 attempt by toy and game console maker Coleco to enter the growing home computer market. Critics and consumers looked forward to the computer after Coleco unveiled it June 5, 1983, but it never lived up to that anticipation. Coleco discontinued the Adam in 1985. Nevertheless, the Adam remains an interesting might-have-been.

Who was Coleco?

Coleco was a leading maker of toys, particularly electronic toys. In the 1970s, it competed with Atari, releasing Pong-like consoles as part of its Telstar product line.

In 1982, it introduced its very successful Coleco Vision game console, which teamed a Z-80 CPU with sound and graphics chips from Texas Instruments. With a computer-grade CPU, graphics and sound chips, the Coleco Vision provided advanced capabilities for its day, much closer to those of the Nintendo NES than the Atari 2600. Coleco also sold an Atari 2600 clone.

Enter the Coleco Adam computer

In 1983, the home computer industry was far from decided. Commodore led the industry in sales, but looked vulnerable. Its VIC-20 computer was underpowered and sales were fading fast. The Commodore 64 was selling well, but Commodore was having trouble keeping up with demand, especially for peripherals like disk drives. The Commodore 64 was a bargain at $299 compared to more expensive computers from Apple and Atari, but a bare $299 computer wasn’t very useful. You really needed a disk drive and a printer to do anything with the system.

Coleco saw an opening. In January 1983, Coleco announced the Coleco Adam computer. For $525, Coleco promised a complete system. It would have 80K of RAM, a full-travel keyboard, tape-based storage, a daisywheel printer, and software including the game Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom and a word processor. It could use an inexpensive television for a monitor, like other home computers of the day. The Adam was a lot like the Texas Instruments TI-99/4A, but by using a Zilog CPU, it was easier to program. It looked like what the TI-99/4A should have been.

The Adam gave protection to the Coleco Vision game console as well. Commodore successfully attacked Atari by saying it made more sense to buy one of their computers rather than a machine that could only play video games. Coleco introduced a version of the Adam that plugged into an existing Coleco Vision console, turning it into a full-blown computer system. This wasn’t a new idea. Rival APF had tried this in 1978-79 with its MP1000 console and Imagination Machine add-on. But the time seemed right in 1983 to try the idea again.

It looked like a winner. It was a real computer. The industry knew how to develop for it since it used well-known and well-understood chips. It could play existing Coleco Vision games, so there was stuff you could do with it on day 1. The kids could do their homework on it with the included word processor, and they could play Coleco Vision games on it.

Why the Coleco Adam computer failed

Coleco would have been difficult to compete with if it had delivered. But Coleco underestimated what it would take to bring the Adam to market. Coleco had to raise the price to $599 and then to $725. Then it failed to meet the release date of September 1. It kept pushing the release date out two weeks and finally managed to release the computer in late October in limited quantities.

Initially Coleco planned to sell 500,000 units in 1983. It only managed to produce about 100,000 units that year, and the defect rate was alarmingly high. Coleco claimed 10 percent of the systems were defective, but retailers reported higher rates than that. One store manager told Creative Computing magazine that consumers returned five of six units he sold.

The video game crash of 1983 was an opportunity for the Adam, with some consumer interest shifting from consoles to computers. But Coleco couldn’t deliver enough product fast enough and what it did deliver was flawed, so it couldn’t capitalize. Meanwhile, Commodore had sorted out its production issues and sold 3 million C-64s that year.

Design flaws

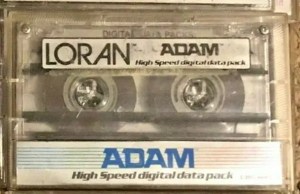

Even when the computer worked, it was less than ideal. The storage device was faster than Commodore’s or Atari’s tape drives. But it was slower than a disk drive. The Adam’s data packs had a tendency to unravel. Worse yet, if you had one in or near the drive when you turned the system on, the magnetic field would erase the tape inside.

The printer gave high-quality output, but was loud and slow and lacked graphics capabilities. It produced good-looking reports and letters, but you couldn’t use it to print greeting cards like your friends who had Apple or Commodore computers, dot-matrix printers, and Print Shop. Not only that, the printer had the power supply for the whole computer system in it, so if the printer broke, the whole computer was unusable. IBM made a similar mistake in the 1990 version of its PS/1 computer, which had the power supply in the monitor.

Consumer magazines gave it mixed reviews. Critics liked the Adam’s keyboard and loved the quality of the printed output, which made the output from Commodore’s printers look amateurish and cheap. But they really didn’t like the decision to put the power supply in the printer. They didn’t like the data packs either.

Stiff competition

Worse yet for Coleco, by the time the Adam shipped, Commodore had most of its supply problems straightened out. A Commodore 64, disk drive, and choice of printer sold for very close to what an Adam sold for.

There was another key difference between Coleco and Commodore. Commodore made its own chips. Coleco bought chips from Zilog and Texas Instruments. That gave Commodore options. It could match Coleco’s pricing and have higher profit margins, beat Coleco’s pricing and match Coleco’s margins, or anything in between.

Commodore’s 1541 disk drive was so problematic it spawned its own clone movement, but it worked better than Coleco’s data packs. Coleco eventually released a disk drive for the Adam, and unlike the Commodore 64, its CP/M compatibility actually worked well. But a disk-equipped Adam couldn’t compete with Commodore’s prices.

Coleco lost almost $50 million due to the Adam’s struggles. In early January 1985, Coleco discontinued the Adam and liquidated existing inventory. In the end, Coleco sold somewhere between 300,000 and 400,000 units in an era when critical mass for success would have been somewhere around 1-2 million units.

Coleco said in 1984 it was betting the company on the Adam’s success and it was right. The whole company went out of business in 1988.

Why Coleco gave up so soon

It may seem strange to give up on a computer just 24 months after announcing it. It’s likely Coleco’s shareholders were getting impatient. The other thing is understanding the computer industry in 1985. In 1985, the industry was shifting fast. Apple had released its first Motorola 68000-based computer the year before. Both Atari and Commodore intended to have advanced 68000-based computers out by summer.

Coleco had a limited window of opportunity with the Adam. And in early 1985, it looked like they’d missed. In hindsight, maybe they were wrong. Commodore’s Amiga was late to market. The Atari ST was interesting but Jack Tramiel was selling the company’s office furniture to keep it afloat. But Coleco didn’t know that. It was sitting there with a bad reputation and a 1983 design. And in 1985 in the computer world, two years seemed like 20. It was looking like it would be hard to match the 1984 sales figures, and Coleco really needed to double or triple its 1984 sales.

Notably, IBM bailed on the home computer industry in early 1985 too. Coleco might have been able to turn it around. But it didn’t have room for any more mistakes. Coleco’s managers had a better idea of the company’s ability to execute in 1985 than we do now.

What might have been

Conceptually, the Coleco Adam computer wasn’t very different from Microsoft’s MSX computers, which were popular in Japan. The biggest difference was Coleco’s use of a TI sound chip instead of a General Instrument AY-3-8910. Had Coleco been able to deliver the Adam in quantity, it’s likely software developers would have adapted their MSX software to the Adam. There would have been lots of software for the Adam very quickly.

Also since Coleco used off-the-shelf parts to build the Adam, it would have been possible to sub the TI sound chip into an MSX machine to turn it into an Adam clone if consumer demand had warranted it.

If Coleco had succeeded in delivering 500,000 Adams in 1983 with a reasonable defect rate, that success would have come largely at the Commodore 64’s expense. In 1984 Commodore was distracted with its Plus/4 experiment. So it’s easy to imagine a scenario in 1984 where Coleco sold nearly as many Adams as Commodore sold 64s. Coleco’s competitors weren’t perfect either.

It’s likely this success would have attracted the attention of Japanese computer makers. Someone would have cloned the Adam. The arrival of inexpensive IBM-compatible computers would have cut into the Adam’s success too. Coleco likely would have either exited the home computer market within a few years, or shifted to a PC-compatible, perhaps imitating the Tandy 1000. But the company as a whole may have survived.

The Coleco Adam computer maintained a cult following long after its demise. With the addition of a disk drive and third-party peripherals, it wasn’t a bad computer. It could run CP/M software and Coleco Vision games, so there was plenty of software for it. But Coleco ran out of time and money.

With better execution, the computer industry could have ended up a lot different. It didn’t, but the Adam is still fun to speculate about. Instead, the Adam is generally remembered as one of the biggest flops of the 80s, where the computer that inspired it, the Imagination Machine, if it’s remembered at all, is remembered as a pretty good computer that failed due to bad timing.

The Coleco Adam’s legacy

The Coleco Adam ended up hurting Atari more than Commodore, but in an unexpected way. At the June 1983 CES, Coleco showed the Adam running an enhanced version of Donkey Kong, with all the levels. Atari CEO Ray Kassar thought they had exclusive rights to produce Donkey Kong for computers. Incensed with Nintendo, Kassar broke off negotiations to have Atari distribute Nintendo’s Famicom console in North America. Kassar left Atari soon after, but his successor never resumed negotiations. Nintendo found another distributor for what became the NES.

If it hadn’t been for the Coleco Adam computer, the Nintendo NES might have come to market sooner, and with an Atari logo on it.

David Farquhar is a computer security professional, entrepreneur, and author. He has written professionally about computers since 1991, so he was writing about retro computers when they were still new. He has been working in IT professionally since 1994 and has specialized in vulnerability management since 2013. He holds Security+ and CISSP certifications. Today he blogs five times a week, mostly about retro computers and retro gaming covering the time period from 1975 to 2000.