Brewing and seafaring are mainstays of ancient human endeavors. Beer was first fermented by at least the 5th millennium BC in Mesopotamia. From the land between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers of the Fertile Crescent, the grain beverage either traveled along trade routes or was spontaneously developed in other ancient civilizations (including Egyptian, Grecian, Roman, Norse, Aztec, Chinese) before landing in northern Europe in the early medieval period. Producing beer became a standard domestic chore in households, and later, on a slightly larger scale, in taverns and monasteries.

It is something of a myth that drinking beer was much safer and more common than imbibing the oft-contaminated water. There was plenty of fresh water abounding in lakes, streams and rivers and good wells. However, for seafarers, those sources were not always in reach. In the maritime world, long before the ration of rum, weak beer on navy ships was the standard provision for sailors. Beer provided some nutrition and needed calories while not harboring harmful microorganisms. It could also soften the hard bread of a long voyage.

The records of the British Royal Navy provide the most detail of what food and drink provisions seafarers received in the Age of Sail. Chief Secretary to the Admiralty and diarist Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) drew up a contract in 1677 that was specific in the rations and their substitutes: one pound of biscuits, two pounds of salted pork, six ounces of butter, and a gallon of beer, among other items including cheese, beef and oatmeal, per sailor per day. While that seems like an awful lot to chug while on duty, this maritime “small” beer was low in alcohol (sometimes less than one percent).

In an appendix to James Cook’s A Voyage towards the South Pole and Round the World Performed in His Majesty’s Ships the Resolution and Adventure (London, 1784), beer is touted as a health beverage. In this volume is a reprinted address to the Royal Society in 1776, entitled A Discourse upon Some Late Improvements of the Means of Mariners. The author, Sir John Pringle (1707-1782), a founder of modern military medicine, reported:

It hath been a constant observation, that in long cruizes or distant voyages, the scurvy is never seen whilst the small-beer holds out, at a full allowance; but that when it is all expended, that ailment soon appears. It were therefore to be wished, that this most wholesome beverage could be renewed at sea; but our ships afford not sufficient convenience. The Russians however make a shift to prepare on board, as well as at land, a liquor of a middle quality between wort and small-beer, in the following manner. They take ground-malt and rye-meal in a certain proportion, which they knead into small loaves, and bake in the oven. These they occasionally infuse in a proper quantity of warm water, which begins so soon to ferment, that in the space of twenty-four hours their brewage is completed, in the production of a small, brisk, and acidulous liquor, they call quas, palatable to themselves, and not disagreeable to the taste of strangers.

The Dutch had effectively found a cure for scurvy in the 16th century, although at this early date it wasn’t understood why beer and fruits prevented scurvy. John Woodall (1570-1643), military surgeon to the British East India Company, recommended citrus to ward off or cure the debilitating disease. But the first to systematically study the benefits of certain food and drink was James Lind (1716-1794). His seminal work, A Treatise on the Scurvy (Edinburgh and London, 1753), made the concept widely accepted. Beer was certainly a more economical remedy than providing fresh fruits. Only later a fixed amount of lemon juice was decreed by the British Admiralty to be added to the provisions for a mariner. Long before the nickname “Jack Tar,” a British sailor in North America was called a “limey” for the habit of sucking on limes.

Beer was to remain the issued drink in Northern Europe for seafarers; when sailing in southern climes, particularly the Mediterranean, wine was preferred. Rum issued to British sailors in the West Indies began to replace beer in the Caribbean from 1655. Grog, a diluted version of rum, was mandated in the 1740s, but beer still ruled the waves. The Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea (1808) stipulates that “In case it should be found necessary to alter any of the foregoing particulars of Provisions, and to issue other species as their substitutes, it is to be observed, That a pint of Wine, or half a pint of Rum, Brandy, or other Spirits, holds proportion to a gallon of Beer.” In the young United States Navy, sailors could keep their own beer. That is, up until 1914 when almost all alcohol was forbidden on ships with the detested General Order No. 99, a prelude to Prohibition in America.

It is oft-stated erroneously (or, at least, not the complete story) that the Pilgrims on the Mayflower put in at Cape Cod Bay in 1620 at the insistence of captain and crew because the beer supply was getting low for the hired mariners return voyage back across the Atlantic. Native Americans had been brewing alcoholic beverages from corn and birch sap long before any settlers set foot on the shores. Less than ten years after the first Thanksgiving, there was enough demand for beer that Captain Robert Sedgwick established and obtained a monopoly on the first New England brewery in Charlestown (Boston). Captain John Smith (1580-1631) in his history of Virginia (The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Iles) reported that there were two brewers in that Colony. In 1632 the Dutch West India Company opened a brewery on Brouwers Street (or Brewers, now the one-block Stone) Street in New Amsterdam (that is, Manhattan). That is often claimed to be the first public brewery in America.

Beer often spoiled or supplies ran out during long voyages. Captain Smith listed in “The charge of setting forth a ship of 100. tuns [tons] with 40. persons, both to make a fishing voyage, and increase the Plantation” from New England needed “26 Tun of Beer and Sider” while at sea. Explorer, navigator and British Navy Captain, James Cook (1728-1779) described repairs and re-provisioning during his A Voyage towards the South Pole and Round the World. He made these observations and provided directions for making spruce beer while anchored in the Queen Charlotte Sound of New Zealand:

We also began to brew beer from the branches or leaves of a tree, which much resembles the American black spruce. From the knowledge I had of this tree, and the similarity it bore to the spruce, I judged that, with the addition of inspissated juice of wort and melasses, it would make a very whole-some beer, and supply the want of vegetables, which this place did no afford …

The juice, diluted in warm water, in the proportion of twelve parts water to one part juice, made a very good and well-tasted small beer … keeping it in a warm place, if the weather be cold, no difficulty will be found in fermenting it.

Captain Cook was following in the wake of Native Americans in North America who had long been drinking spruce beer (actually, a water-infused drink made from the leaves of spruce, pine or cedar trees), also to ward off the seafarers’ scourge of scurvy during the long winter months. Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) and his crew, when they landed in what is now Quebec in 1535, survived with this abundant source of vitamin C. There is evidence that spruce beer was drunk by sailors plying the Baltic Sea as early as the 16th century. Ship-brewed spruce beer was a common undertaking during the 18th-century explorations of the Pacific. It was on board the ships searching for the lost Franklin Expedition in the Arctic in the 1850s.

At a time when beer consumption was rapidly increasing, scientist Louis Pasteur was a pioneer in his study of the process of fermentation and the role of yeast to prevent beer from spoiling. His method became known, of course, as pasteurization. It was beer (fun fact) and not milk that was the first beverage that he studied for preservation. Finally, with this killing of pathogenic microbes, beer could be prevented from souring during long voyages but, alas, the Age of Sail (usually dated as the period of 1571 to 1862), was ending.

There are some who believe that the origin of every phrase and most words in the English language can be traced to the nautical past. For example, this post started out employing in the first sentence “mainstay,” meaning pillar or foundation. It derives from a stay that extends from the maintop to the foot of the foremast of a sailing ship. “Three sheets to the wind,” meaning drunk, comes from the lines (ropes or sheets) that secure a sail; if they are flopping about in the wind, the ship wobbles like someone who has overindulged. International Beer Day is on August 4th. Before this designation, there was Beer Day on United States Navy ships, when all hands were provided the brew while underway while on long voyages and at the discretion of the Commander.

There is much that combines the maritime and beer worlds. So, hoist the mainsail and a tankard and salute the storied nautical history of the drink as found in primary and secondary sources of the collections of the Smithsonian Libraries. There are vast seas to explore beer in its varied collections of voyages of exploration, medicine, chemistry, botany, culinary, trade, military history, and travel literature. Then “Splice the mainbrace!*”.

*Originally one of the most difficult emergency repairs on a ship, the phrase became the order to grant the crew and extra ration of drink.

Beer in the Library:

For more on the provisioning of sailors in the Age of Sail and the use of the term “small beer” (link here)

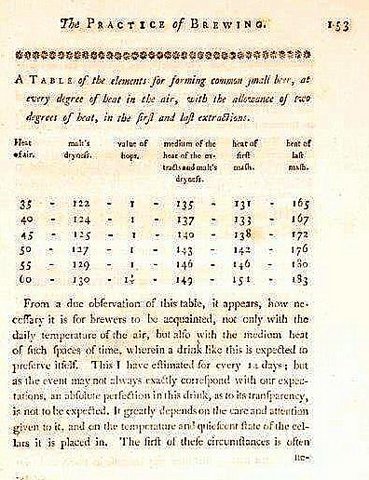

The Dibner Library contains the seminal work, The Theory and Practice of Brewing, by Michael Combrune (London, 1762). The author, a member of the Worshipful Company of Brewers, advocated a more scientific approach and is credited with first using a thermometer in the brewing process.

The Dibner Library contains the seminal work, The Theory and Practice of Brewing, by Michael Combrune (London, 1762). The author, a member of the Worshipful Company of Brewers, advocated a more scientific approach and is credited with first using a thermometer in the brewing process.

Producing beer in the home was still a domestic undertaking into the 19th century (link here). Homebrewing is now resurgent.

The Dibner Library has a well-thumbed and marked copy of Instructions for Officers of Excise in the Country, concerned in Charging the Duty on Beer (London, 1816).